The cumulative exposures graph: Increasing and decreasing slopes

The cumulative exposures graph details the number of users exposed to your experiment over time. The x-axis displays the date when the user was first exposed to your experiment. The y-axis displays a cumulative, running total of the number of users exposed to the experiment.

Each user is only counted one time, unless they're exposed to more than one experiment variant. If they're exposed to more than one variant, they count once for each variant they experience.

Note

Interpreting the cumulative exposure graph

This article covers cumulative exposure results with:

- Increasing slope (the lines consistently go up and to the right.)

- Decreasing slope (the lines go up and to the right, but the cumulative exposure slows down over time.)

Check out other help center articles on interpreting cumulative exposure results with:

Increasing slope

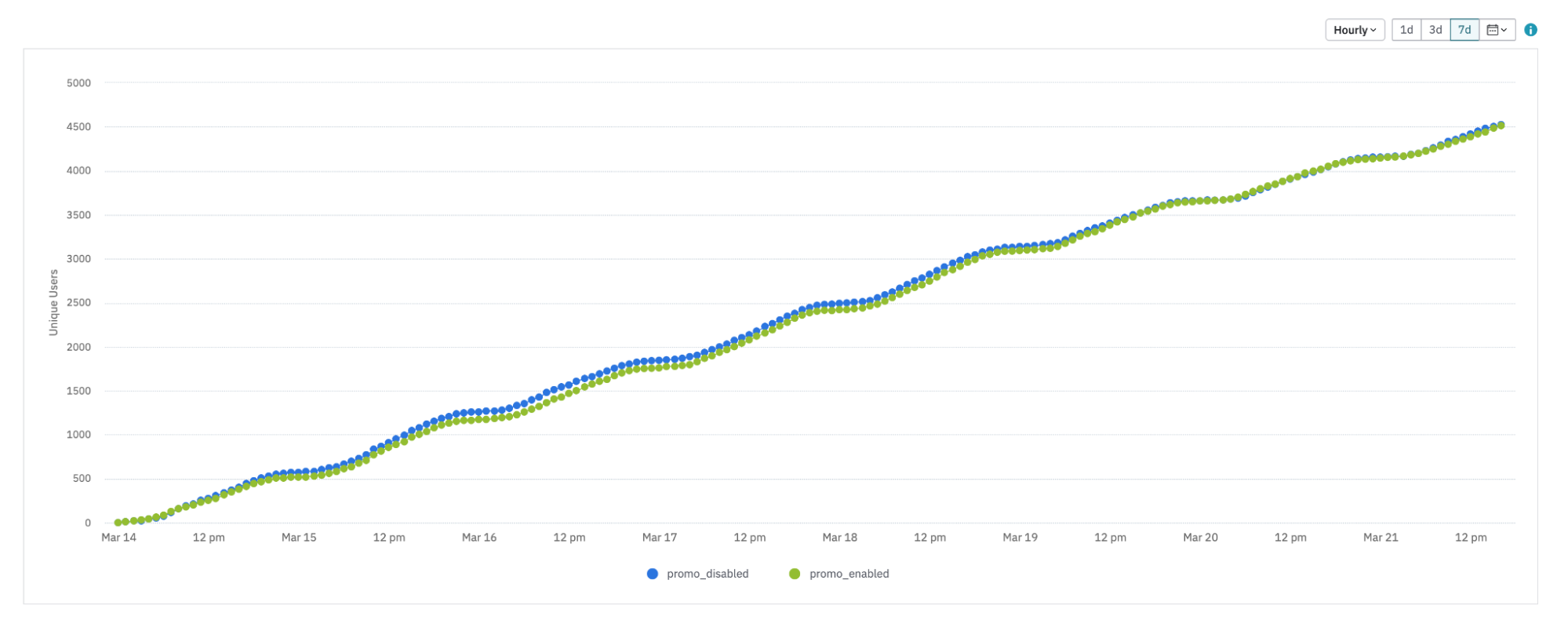

In the graph below, each line represents a single variant. March 20 is the first day of the experiment, with 158 users triggering the exposure event for the control variant. A day later, a total of 314 users receive the control variant. That number is the sum of exposures on March 20 and March 21.

This is a standard cumulative exposure graph with an increasing slope.

Mathematically speaking, the slope of each line is the change in the y-axis divided by the change in the x-axis:

∆y / ∆x = (cumulative users exposed as of day T1 — cumulative users exposed as of day T0) / (number of days elapsed between T0 and T1) = Number of new users exposed to the experiment, per day, from day T0 to day T1.

Additional aspects of this graph:

- It’s cumulative, which means the y-axis doesn't decrease. The slope of the line is the number of new users exposed to your experiment every day. The line may slow down, or even stop growing completely. But there isn't a cumulative exposures graph where the line peaks and then drops.

- There’s a dotted line at the end, which means there is incomplete data for those dates. Review this article for more information.

- The two lines don't track each other seamlessly. That’s because each line represents a unique variant, and exposures can differ slightly between variants, even when they’re set to receive the same amount of traffic.

- Both variants are on a steady growth path. This means there is no seasonality. If, for example, users were more likely to engage with your product (and therefore more likely to be exposed to an experiment) on weekdays, this is would appear in the chart. On weekends, the y-axis value would increase more slowly.

Hourly versus daily setting

Often, changing the x-axis to an hourly setting, as opposed to daily, offers new ways of understanding your chart:

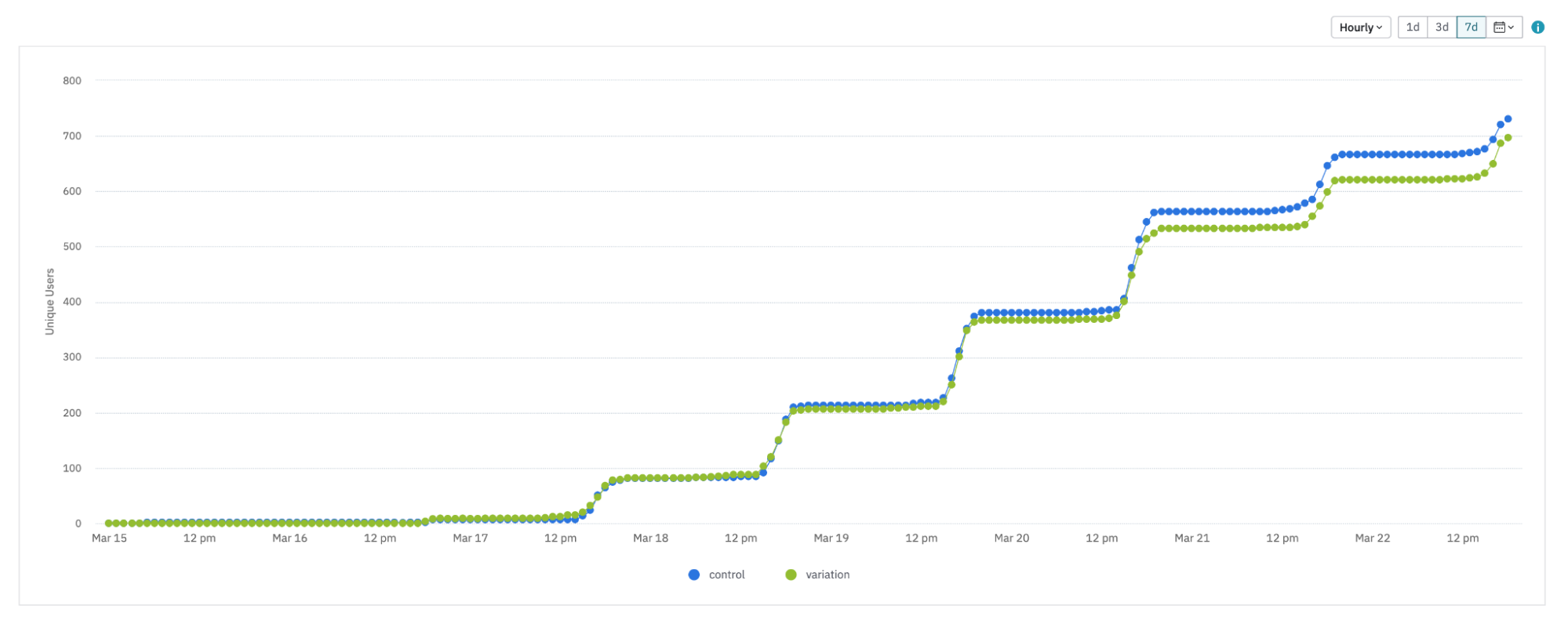

Here, the trend is still linear. But since this is an hourly graph, from 9 PM to about 5 AM, almost no additional users get exposed to the experiment. This is probably when people are sleeping, so it stands to reason they aren't using the product. This is something that wouldn't be apparent in the daily version of the graph.

This is a more extreme example. Here, the exposures look like a step function. In this case, it could be that the users who have already been exposed to your experiment at least once are evaluating the feature flag again during these “flat” time periods.

Decreasing slope

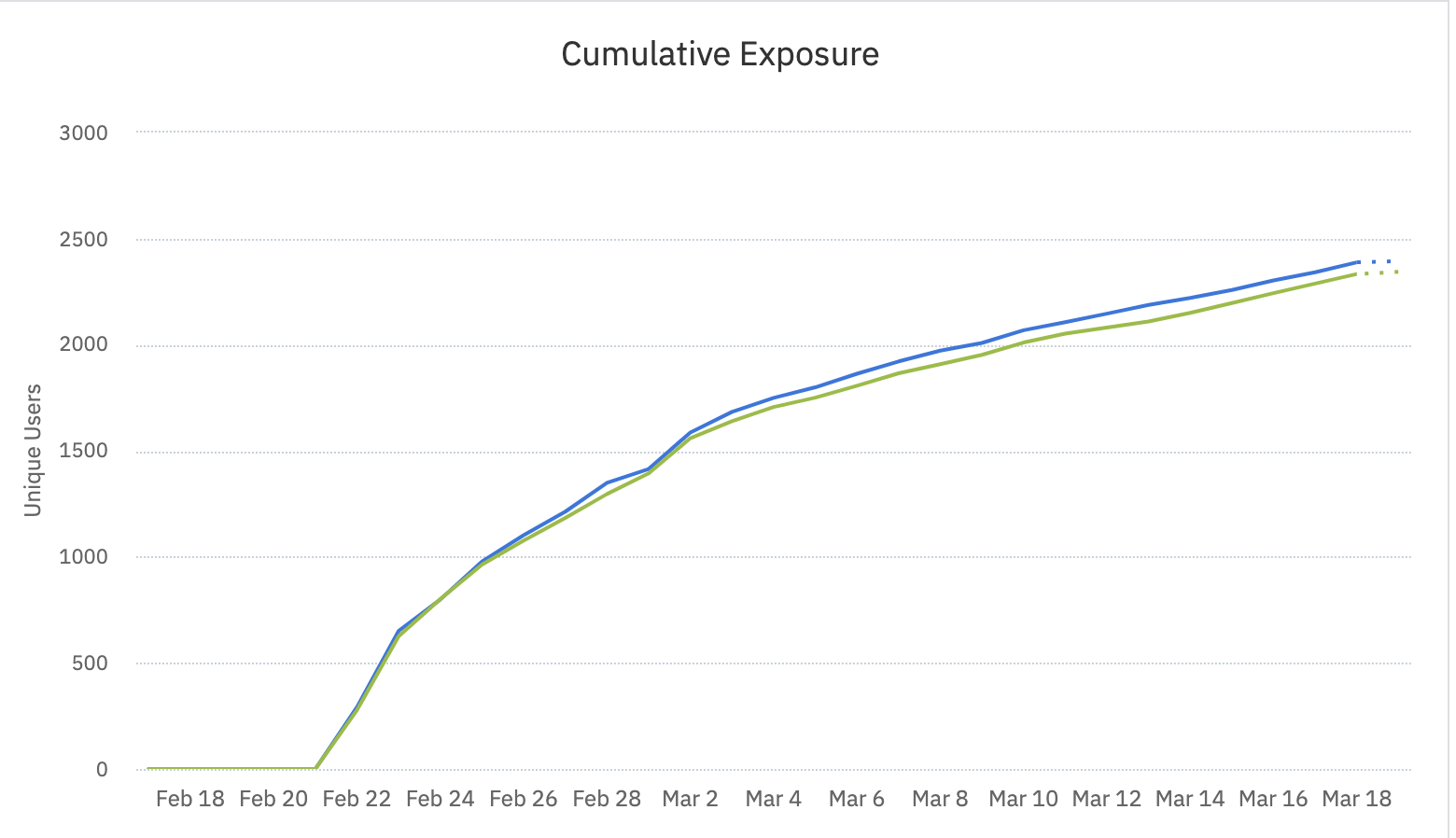

Sometimes, an experiment’s cumulative exposures can start out strong but then slow down over time.

When this experiment launched, each variant was exposed to about 280 new users each day. But toward the end, those exposure rates were down to about 40 new users per variant, per day.

Static cohorts can limit your experiment

The cumulative exposures can flatten out over time when you target a static cohort, for example, one that doesn't grow or shrink on its own.

For example, imagine a static cohort with 100 members. On the first day, 40 of those users saw your experiment. That leaves only 60 more users eligible users to include in the future. With each passing day, there are fewer and fewer users who can enter into the experiment in the first place, and the slope of your cumulative exposures graph inevitably flattens.

If you’re using a static cohort in an experiment, consider rethinking how you’re using the duration estimator. Instead of solving for the sample size, you should ask what level of lift you can reasonably detect with this fixed sample size.

When using a cohort in this way, ask yourself whether the cohort is actually representative of a larger population that would show a similar lift if more users were exposed to the winning variant. You can’t assume this, doing so would be like running an experiment in one country and then assuming the same impact in any other country.

Other possible causes for decreasing slope

- Using a dynamic cohort that isn’t growing quickly enough, or the number of users that interact with your experiment might be limited.

- How you handle sticky bucketing: If users enter the cohort and then exit, do you want them to continue to receive the experiment (for consistency’s sake) even though they no longer meet the targeting criteria?

- The experiment is initially shown to a group of users who aren't representative of users exposed later. Users who have been using your product for 30 days may interact with the feature you’re testing differently than those who’ve been around for 100 days, for example. Consider running your experiment for longer than you had originally planned, to make sure you’re studying the effect of the treatment on a steady state of users.

- Users gradually become numb to your experiment and stop responding to it after repeated exposures.

Bear in mind that just because the cumulative exposures graph has flattened out doesn't mean that the experiment has a limited impact. It all depends on the specifics of your users’ behavior.

Seeing this kind of graph has serious implications to the duration your experiment needs to run. The standard method of calculating the duration of an experiment is to use a sample size calculator and divide the estimated number of samples by the average traffic per day. Here, that’s not the case. Typically, you’ll need to run the experiment for longer than expected, as the denominator was overestimated.

November 6th, 2024

Need help? Contact Support

Visit Amplitude.com

Have a look at the Amplitude Blog

Learn more at Amplitude Academy

© 2026 Amplitude, Inc. All rights reserved. Amplitude is a registered trademark of Amplitude, Inc.