Zynga Analytics at its Peak

During its peak, Zynga was a powerhouse at using data and analytics to optimize their games for virality and revenue.

This is the second post in our series on the Evolution of Analytics. You can catch the first post, about hit counters and early web analytics, here.

Zynga’s main offices in San Francisco. Image from Slate.

If you can’t measure something, don’t build it. If you couldn’t measure the results, don’t try it. Because how do you know it’s working? How do you know it isn’t?”Andrew Trader, Founding team & former VP of Sales and Business Development at Zynga

Zynga, the gaming company known for breakout Facebook games like FarmVille, is largely credited for pioneering social and casual gaming as we know it today: a precursor to new mobile favorites like Candy Crush. During its peak, Zynga was a powerhouse at using data and analytics to optimize their games for virality and revenue.

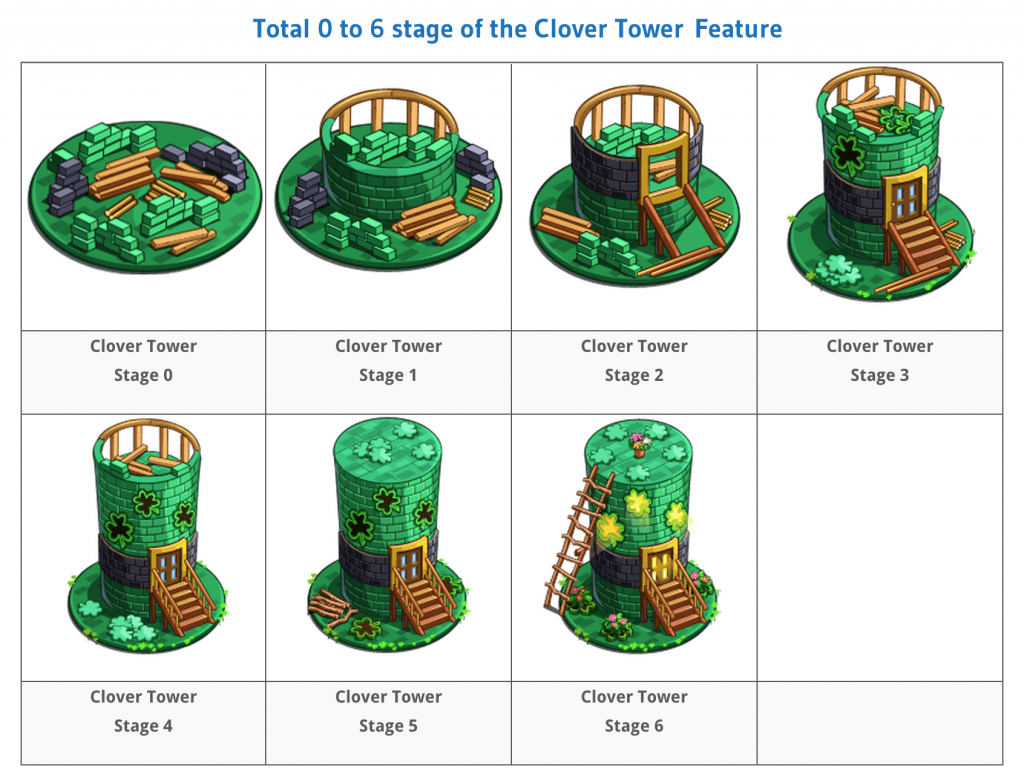

Niko Vuori, a former general manager at Zynga, related one example from the company’s popular “Ville” games (FarmVille, FrontierVille, etc). In these games, players can collect different parts to assemble into a final product like a house, car, or garden. These products are called buildables. Players can either collect parts from their Facebook friends, or pay money for parts as an in-game purchase.

The data showed that players wouldn’t pay to merely make progress on a buildable, but they would pay to complete it. So, a user might pay for the 9th and 10th pieces of a 10-part car, but they wouldn’t pay for pieces one through eight – those would be gathered from friends.

This is an example of a buildable from Zynga’s FarmVille game. To build a complete Clover Tower, players need to either collect these pieces or pay for them. Source

Based on this insight, Zynga optimized for monetization by creating buildables that had a number of parts just a bit out of reach of a users’ friend network. That way, a player would get most of the parts from their friends, but would be unlikely to gather all of the parts from their network. Since they were so close to completion, they would just pay for the last one or two parts to complete the buildable.

In this post, we take a look at Zynga’s data-driven approach to game development that made these sorts of insights possible. The company built its own data tracking infrastructure, dubbed ZTrack, at a time when such advanced solutions were pretty much unheard of. Zynga used this data to optimize and improve their games; Zynga’s former VP of Analytics Ken Rudin is famously quoted as saying that Zynga was “an analytics company masquerading as a games company.”

While Zynga has received a lot of press for its organizational issues and over-dependence on Facebook, the company is still widely respected for its early adoption of data-driven product development. Zynga alumni brought these practices to their subsequent projects, spreading the strategies to industries far outside the world of social gaming.

A Metrics-Driven Culture

According to Andrew Trader, a member of the founding team, Zynga’s most important corporate value was its focus on metrics.

At the time, not many game studios were tracking their users, and game design was still largely based on gut instinct and user feedback rather than numbers. From the start, Zynga differed from other gaming companies by hiring product managers from finance or consulting backgrounds, who were used to approaching problems analytically.

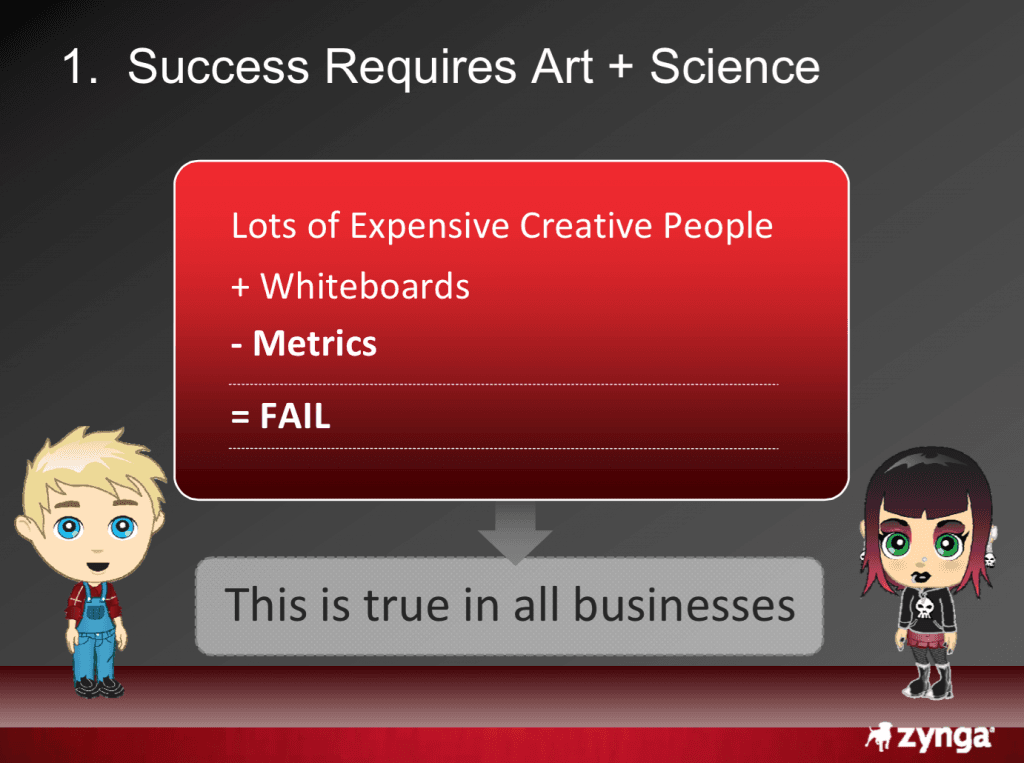

The company promoted data transparency. Everyone had stakes in the metrics, from software engineers, to the product managers, to the CEO. Zynga executives stressed the importance of having both art (the ability to generate great game ideas) and science (the ability to test and find out whether the ideas are any good).

The following slide is from a presentation that Ken Rudin, Zynga’s former VP of Analytics, gave in 2010.

Zynga stressed the importance of having science (metrics and the ability to test hypotheses) in addition to the art and creativity of game-making. This slide is from a presentation by Ken Rudin in 2010.

How did Zynga decide what to track? During game development, the product managers would define the data hierarchy of their games and what actions the game involved. Setting up proper tracking was crucial to launching a new game. Roy Sehgal, an early Vice President and general manager at Zynga, explained:

ref “Our philosophy in the beginning was to fully instrument the product and rigorously test the analytics tracking before launch. We realized the importance of using data to understand user behavior and product performance, and then creatively iterating the product experience post-launch. We would delay a launch if we could not properly track the metrics. Data and analytics were not an afterthought.”

Pioneering Event-Based Analytics

While this level of event tracking and analysis is something you expect from any successful, high-growth company today, at the time Zynga was doing something fairly new.

Said Sehgal, “The rigor of the metrics and analyses were definitely things that are taken for granted today. We were measuring things in a way that not everyone was doing.”

Back in 2008, we didn’t have the plethora of self-service analytics platforms that are available today. The only way to do this kind of analysis was to build it in-house – and that required a significant investment of engineering man-hours and resources. This meant that it was very difficult for resource-strapped companies to have the same kind of data access and analytics that a company the size of Zynga could build.

Zynga built its internal analytics platform, called ZTrack, at a time when many companies were still focused on hits and pageview-centric web analytics. Pageviews were important for measuring impressions and driving ad revenue.

However, as businesses began moving away from ad-based models to consumer pay models, pageviews became less important, and sophisticated organizations like Zynga began tracking user actions on their sites or in their products.

Building Analytical Models Before Game Launch

Before launching any Zynga game, the team built a detailed analytical model for the game’s performance. The model took into account factors like the viral hooks built into the product and the user acquisition channels. From this data, the model attempted to predict key metrics, including the number of new installs per day and how that would decay over time, virality K-factor over time, Day 1 retention over time, and revenue per daily active user.

The team also modeled how they should price items in the game’s virtual economy. Teams used these models as a basis for understanding how to engineer the game for maximum growth, engagement, and revenue. These models also provided a baseline for comparison, so that as soon as the game launched, the team could quickly gauge whether or not it was on track to meet expectations.

The Metrics that Matter to Zynga

So which metrics really mattered to Zynga? From our conversations with former Zynga product and general managers, we got an interesting look into how they measured the health and success of their games.

The 3 R’s: Reach, Retention, Revenue

Zynga focuses on the 3 R’s: Reach (how many users), Retention (how many users stick with the game), and Revenue. Retention is key: if you have retention, the other 2 R’s will follow.

Zynga realized that Day 1 retention (the percentage of new users who come back one day after they first play a game — Day 1) was a good early indicator of long term retention. In other words, a user who didn’t come back on Day 1 was unlikely to stick with the game in the long run.

What makes Zynga’s case interesting (and a bit different from most non-gaming companies) is that each game had a fairly fixed lifecycle, on the order of 12-24 months. Which product metrics are most important depends on where the game is in its lifecycle. For a brand new game, teams focused on growing their reach. This means they religiously tracked daily installs, daily new users, Day 1 retention, and payer conversion.

As a game matured, about 3 months after launch, teams shifted their focus from growth to maximizing revenue.

Behavioral Cohorting

Zynga heavily utilizes cohort-based analysis. A cohort is any group of users isolated by something they have in common, whether that’s game install date, age group, or location. At Zynga, product managers also grouped users by their actions or level of engagement with a specific feature, also known as behavioral cohorting.

By comparing retention or revenue between cohorts, analysts could better understand which actions in the game predicted that a user would stick with a game for a long time, or which features led to users converting into paying users.

User Walk

Another type of analysis, called the user walk, answered the question: How did our active users change from the previous week? Say you went from 1 million to 1.2 million daily active users over the course of a week. What were the sources of those 200K users? For the user walk, analysts broke down how many users were new installs, how many were reactivated, and how many were becoming inactive, as well as the sources of those different user cohorts. The user walk provided a granular view of the sources of where you were gaining and losing users.

First Time User Experience (FTUE)

Before launching a game, product managers identified the 30 or so steps that a user would engage with in their first session: their first time user experience (abbreviated FTUE). If a game wasn’t performing as expected, the first thing they looked at was the FTUE. Teams looked for any unusual drop-offs between steps, which could indicate an area where the user experience could be improved, or as was often the case, where there was a bug.

Too Data-Driven? Sacrificing Long-Term Growth for Short Term Gains

Although Zynga’s focus on metrics led to extremely successful growth and revenue initially, some Zynga alumni think that the company may have been too data-driven during their time there (things may be a bit different today). One former product manager commented that with Zynga’s intense focus on short term, measurable wins and immediate metrics like daily active users, they often missed out on things that are harder to measure, such as improving the overall usability of a game. He thought that “data was used as an excuse for going after short term gains.” By trying to maximize revenue, the art of making games was lost. Vuori added:

What ended up happening is people were maybe exceptionally focused on the data and didn’t spend enough time looking at the qualitative gameplay. We did [look at qualitative factors], it’s just that the quantitative side always won out.”

Sehgal generally supported this sentiment of balancing quantitative and qualitative factors. “You can absolutely become overly dependent on your data. Data-driven is a loaded term. I believe you need to be hypothesis-driven, and use data to validate (or invalidate) your hypotheses. It’s not necessarily that the data is telling you what change to make. The data identifies where your hypotheses were right or wrong and highlights areas of potential improvement to the user experience. Then you need smart, creative people to come up with new innovative solutions to test and improve the experience for users.”

Flash Sales: Boom or Bust?

Sometimes, having too narrow a focus on short-term gains can cost you long term revenue, as was the case with Zynga _ flash sales_. In Zynga games, there are virtual goods (like the buildable parts we mentioned earlier) at a set price. The first time Zynga ran a sale on these, it was immensely successful. Revenue on that day shot through the roof.

Based on those revenue results, Zynga started running flash sales on a regular basis. At first, these sales resulted in record revenues any time they happened. But eventually, the strategy backfired. Users came to expect the sales, and Zynga found themselves running bigger sales more frequently just to get users to buy more virtual currency. As they did this, they caused their in-game economy to hyperinflate.

Over the long term, the sales strategy was a net negative, as users had more virtual currency than they could spend, and sales became less and less effective. In the short term, the data suggested that sales were a great driver of revenue: more users were converting to buyers, users were spending more, and revenues were higher.

In the long term, however, Zynga was basically just shifting revenue from the future to the days of the flash sales, and inflating their virtual currency.

Where Did All the Poker Players Go?

Zynga Poker. Source

Another example of how Zynga might have been too narrowly focused on its data comes from Zynga Poker. All Zynga teams keep a hawk-like watch on daily active users (DAUs), and there are automated alarm systems that go off if DAUs dip below a certain threshold compared to previous numbers.

One day, the number of DAUs on Zynga Poker dropped drastically, setting off the alarms. Analysts scrambled to figure out what was wrong. They couldn’t find any explanation for the drop in users, and a few hours later, things were back to normal.

A couple weeks later, the users dropped through the floor again, only to bounce back up. Analysts spent hours trying to figure out what was wrong – until someone thought to look at the time of soccer matches. Zynga Poker’s user base is mostly young males, with a wide international reach, and it turned out the drops in usage coincided with popular soccer matches. “It was this funny moment where the data was telling us something was broken, something was wrong, something was horribly wrong,” recalled Vuori. “Where have the users gone? They’ve disappeared, something must be broken.” Vuori has since co-founded Rocket Games, an independent studio that focuses on slots games. At Rocket Games, he thinks they have a more balanced approach to data. Says Vuori,

ref “The main thing that I think a lot of us have taken from Zynga is that data definitely has its place, it helps you make decisions. In the absence of data, it is hard to prioritize things. It’s like, ‘I don’t know, my hunch is as good as your hunch.’ That being said, data should not rule your world.”

Vuori rejects Zynga’s view that any new feature or idea needs to have numbers to back it up. “You should still be open to doing things that are different, that are gut-driven. We’re still very heavily hypothesis-driven, but we are okay with taking bets that don’t have all the numbers to back it up.”

Special thanks to Roy Sehgal, Niko Vuori, and another former Zynga product manager (who preferred to be unnamed) for providing insight and stories from their time at Zynga for this post! Roy Sehgal is an Angel investor in Amplitude, and Niko Vuori is now Co-founder and COO at Rocket Games, an Amplitude customer.

Thanks for reading! In a few weeks, we’ll post our third installment of the Evolution of Analytics series: our vision of the Future of Analytics and the types of things we’ll be able to accomplish as tech and data science techniques improve.

Alicia Shiu

Former Growth Product Manager, Amplitude

Alicia is a former Growth Product Manager at Amplitude, where she worked on projects and experiments spanning top of funnel, website optimization, and the new user experience. Prior to Amplitude, she worked on biomedical & neuroscience research (running very different experiments) at Stanford.

More from Alicia