5 Cognitive Biases Ruining Your Growth

This is a guest post by Alex Birkett, Growth Marketer, ConversionXL.

As data-driven as we try to be, all organizations are essentially and necessarily human-driven. And humans, naturally, are riddled with irrationality and biases.

No one is exempt. And while you can’t totally avoid biases, just being aware of them and vigilant can help you mitigate the downsides. Besides, if you’re not aware that you’re biased, that’s simply your Bias Blind Spot.

The biggest problem with biases is that they work under the radar. You can think you’re making data-driven decisions while totally messing up. This is bad because your confidence increases even while driving decisions based on inaccurate inferences.

So to help you recognize some of the most common biases that afflict analytics, optimization, and growth, we’ll outline five biases and what to do about them. They are as follows:

- The Narrative Fallacy

- Confirmation Bias

- Dunning-Kruger Effect

- Backfire Effect

- Bandwagon Effect

1.) The Narrative Fallacy

Humans like to simplify things. We like stories. When things aren’t coherent – when they’re random and unpredictable – we, without even trying to, weave these disparate events into a cohesive narrative so we can feel smarter and more in control of our environment.

This, in a nutshell, is what Nassim Taleb coined as The Narrative Fallacy. He defined it as “our limited ability to look at sequences of facts without weaving an explanation into them, or, equivalently, forcing a logical link, an arrow of relationship upon them.”

Once you know what the Narrative Fallacy is, you see it everywhere. Ever read an article on the “habits of successful people” or the comments section on a WhichTestWon blog post? Everyone is trying to explain why the blue button beat the red button. Was it increased clarity? Was it because blue makes people feel calm and secure? Ask 12 different people why an A/B test won, and you’re likely to get 12 different answered.

Problem is, you can’t explain (and it doesn’t matter) why something won.

Similarly, we use the Narrative Fallacy to look back at events in our own lives (or others’) to establish causation where there is none. Then, we use these causal inferences as rules for future behavior. Because there was, in actuality, no causality, this is dangerous.

Ryan Holiday recently wrote an article for Fast Company about the narrative fallacy. As he explained it, commencement speeches are littered with the narrative fallacy, as they attempt to weave grand and inspiring narratives around success, such as Larry Page telling students to judge their ambitions on whether or not they could “change the world.”

Even though Google did not start as an ambition to change the world, but rather as an idea Larry Page and Sergey Brin had while working on their dissertations at Stanford. As Holiday put it:

“Economist Tyler Cowen has observed that most people describe their lives as stories and journeys. But giving in to this temptation can be dangerous. Narratives often lead to an overly simplistic understanding of events, causes, and effects—and, often, to arrogance. It turns our lives into caricatures—while we still have to live them.”

In optimization and growth, this kind of storytelling is particularly dangerous because, essentially, it is limiting to your experimentation. As Andrew Anderson put it:

“By creating these stories all you are doing is creating a bias in what you test and allowing yourself to fall for the mental models that you already have.

“You are limiting the learning opportunity and most likely reducing efficiency in your program as you are caught up the mental model you created and not looking at all feasible alternatives.”

Also related is what some call the Causation Bias, defined as the “tendency to assume a cause-effect relationship in situations in which none exists (or there is a correlation or association).”

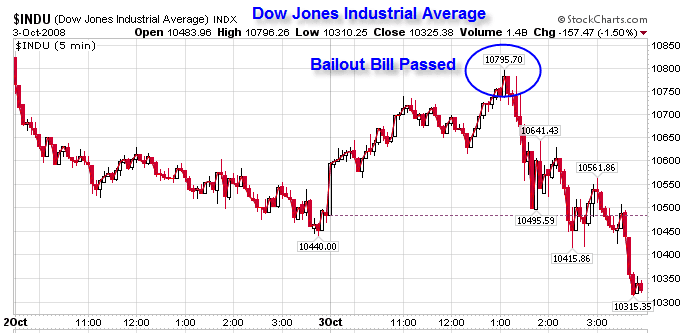

The Narrative Fallacy is known as a Post Hoc Rationalization, one of many types of bias that assert the logic of “after this therefore because of this.” Another name for this same behavior (assigning a pattern to random behavior) is the Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy.

To illustrate it, here’s a story.

Imagine a cowboy shooting at the side of a barn at random. When he’s done he walks up to the barn and notices that there is a large cluster of bullet holes in one section of the barn. He then paints a bull’s-eye over the area where there are a large number of holes. To anyone walking up, it looks like he was a good shot and mostly hit where he was aiming.

According to the You Are Not So Smart blog, “When you desire meaning, when you want things to line up, you forget about stochasticity. You are lulled by the signal. You forget about noise. With meaning, you overlook randomness, but meaning is a human construction.”

What to do about it? Avoid HARKing (hypothesizing after the results are known), and try not to cherry pick data points to support your cause. Optimization expert Andrew Anderson also wrote some advice:

“If we are following the data and disciplined, then we know how we are going to act based on the results, not why the results happened. If you are disciplined in how you think about users, then you know that a story or a single data point will never tell you anything. If we really want to make things personal, then we won’t force “personas” on people, but instead let data tell you the causal value of changing the user experience and for whom it works best.”

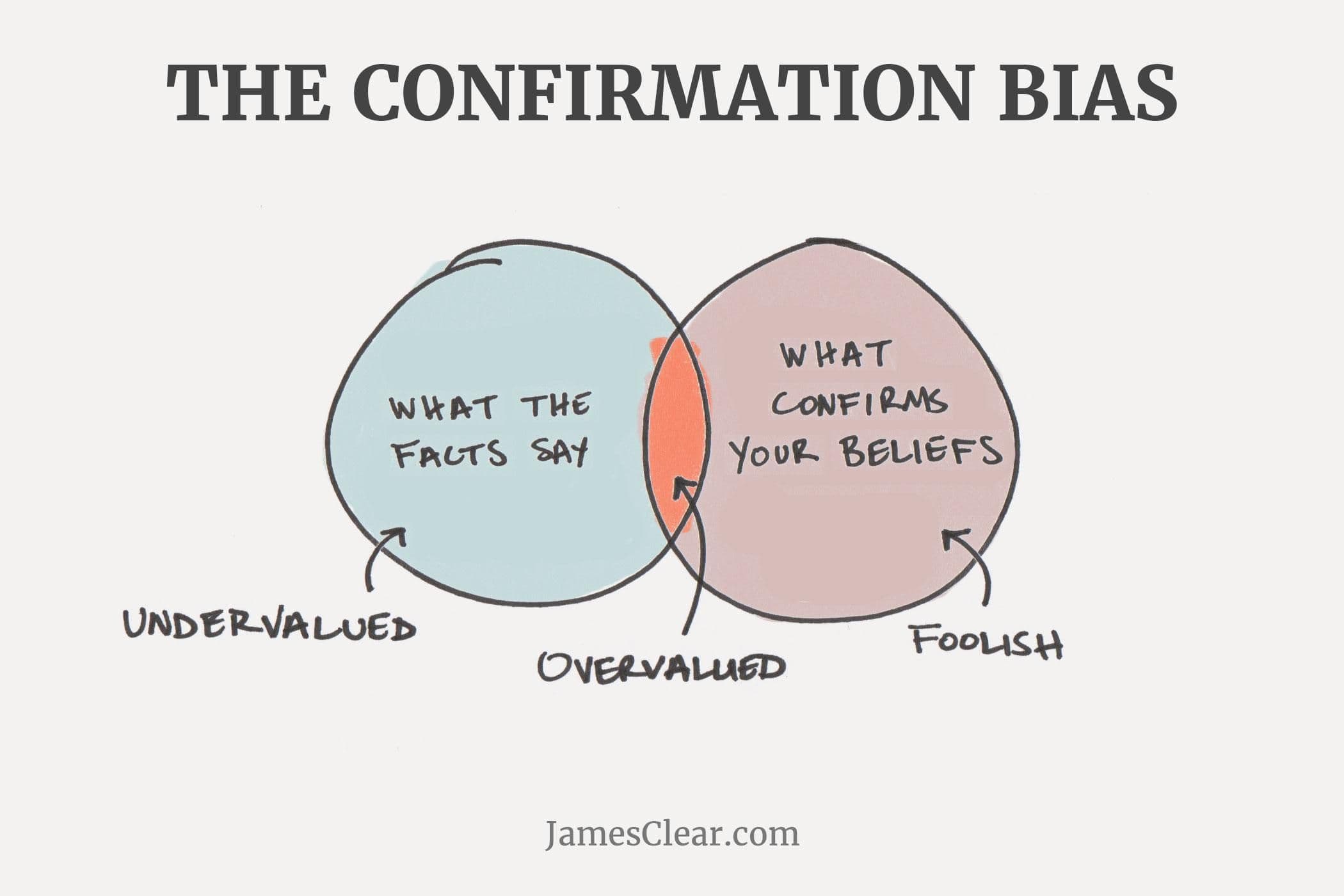

2.) Confirmation Bias

Confirmation Bias is well known and very common. It is defined as “the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs or hypotheses, while giving disproportionately less consideration to alternative possibilities.”

You exhibit confirmation bias when you actively seek out and assign more weight to evidence that confirms your hypothesis, and ignore or underweigh evidence that could disconfirm your hypothesis. Basically, you start with a strong opinion and do what you can to the data to conclude with that opinion as well.

There was a study in 2008 that showed people who already supported Obama were the same people buying books which painted him in a positive light. People who already disliked Obama were the ones buying books painting him in a negative light.

It’s also been shown that confirmation bias is rampant in scientific literature. Have you heard of p-hacking? It’s when one tweaks the variables to get the answer they wanted. It’s not uncommon – not close to uncommon.

In business, this could be as simple as an executive stopping a test early (A/B testing sin #1) one they get the result they wanted.

Or, if there are multiple KPIs that conflict, it’s as easy as cherry picking which ones you think are most important based on what you want to conclude. E.g. variation B wins big at clicks and engagement (micro-conversions) but actually drops revenue per visitor by a little bit. If an opinionated executive wants B to win, he can make an argument for the case by cherry picking data.

Have you established a single core metric – the one metric that matters? If not, you should. It’s one of the strongest ways to mitigate post-hoc confirmation bias (establish it before you run A/B tests, not afterwards).

Of course, confirmation bias is even worse with qualitative data – such as surveys or user testing. If you’re running user tests, and you think that a navigation bar is confusion, every time a user stutters near the bar you’ll notice it (ignoring the 90% of time they didn’t).

In a survey, you could skew questions based on what you want to hear (leading questions). Or you can, during analysis, pick and choose answers based on what you want to hear. Since it is qualitative, it’s easy to lump answers into categories even if, objectively, they don’t belong there.

It’s like my college english professor always said, regarding literature analysis: “you can always find what you’re looking for.” Image Source

What’s the solution? You can’t fully avoid confirmation bias, but by being aware that it exists, you can perhaps notice when it’s happening and put a stop to it.

That, and you should always establish clear metrics upfront so there’s no post-hoc justification and cherry picking. And always have a neutral party review survey questions.

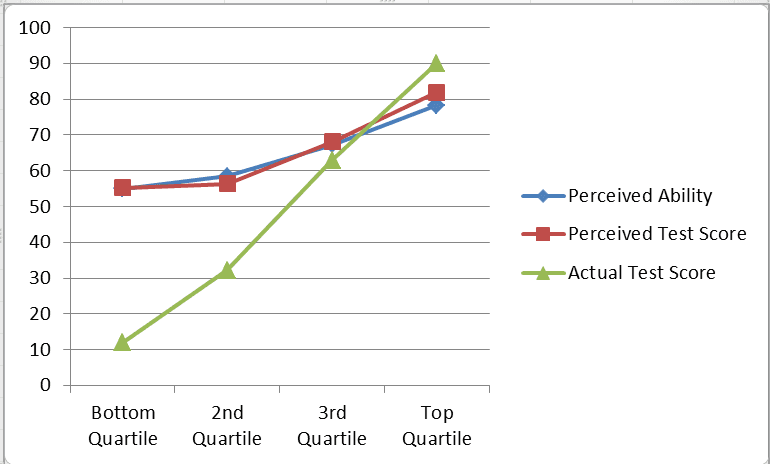

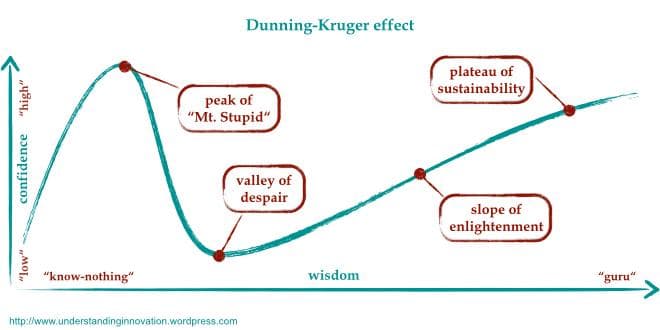

3.) Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is when people who are incompetent or relatively unskilled think they are much more skilled than they are. They’re overconfident in their actions because they don’t know that they don’t know. In other words, “…incompetent people do not recognize—scratch that, cannot recognize—just how incompetent they are.”

This also suggests that highly skilled individuals could underestimate their competence and therefore think that tasks that are easy for them are easy for everyone. Image Source

You can see how this would be detrimental on many levels.

One reason the DK Effect can be harmful, put forth by Andrew Anderson on the ConversionXL blog, is that it can lead to faulty decision making. It can lead to decisions being based on persuasion, not data. Here’s how he put it:

“There is a direct correlation between sociopathic tendencies and positions of power in most businesses, and this is one of if not the primary cause of this. The corollary effect of people who know a lot about a subject being less confident leads to cases of persuasion winning over functional knowledge. If you ever want to know why people still have “I think/I believe/I feel” conversations this is why.”

An example with conversion optimization: your boss knows better than you. Why would you even worry about changing the hero image? Clearly, the call to action is the most important, no matter what the data says (and even though your boss has never run an A/B test).

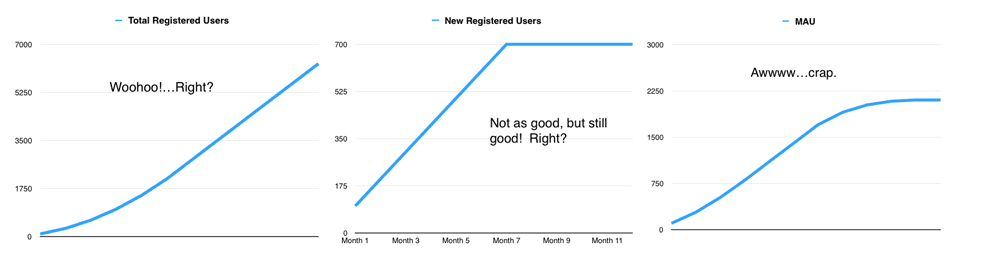

An example with analytics: someone with a certain level of authority and respective reads analytics totally wrong and therefore focuses on inauthentic growth. Their lack of competence and overconfidence sways the company to focus on the wrong things…

If there’s such a discrepancy between confidence and competence according the DK Effect, then it also means problems occur when one discovers they don’t know as much as they thought they did.

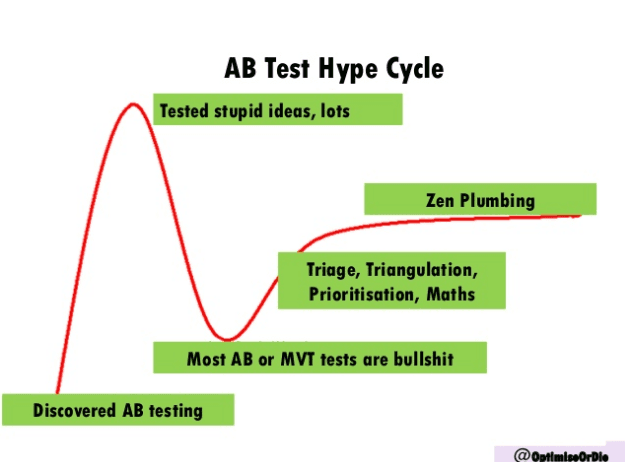

In conversion optimization, Craig Sullivan refers to this period as the “Trough of Disillusionment.” It’s when you realize you’re not as awesome as you thought and things start to get difficult. You begin to think quitting would be a desirable option. Image Source

Or we could call this the valley of despair:

Put someone at the peak of Mt. Stupid up against someone in the valley of despair and Mt. Stupid will win out in confidence, even though they’re clearly less qualified.

The solution? It’s all about the system. As Andrew Anderson put it, “You have to be able to put every idea through a system that maximizes impact to the bottom line of the business and not just their egos.”

A culture of experimentation helps blunt the trauma of hard defeats, and it also dissuades team members from fighting too hard for their own ideas. Create a culture that doesn’t bind professional success with the predictive value of ideas, but rather with a discipline for discovery and a code of data-driven experimentation.

4.) Backfire Effect

A friend of mine told me a story from his consulting days that explains the backfire effect well.

He was working with a large technology client, analyzing their data and consulting them on strategy. Noting that they had never run any controlled experiments on any of their spending, he dug into the effectiveness of their direct mail spending and found they were wasting tons of money in certain geodemographic segments.

Now, from an outsider’s point of view, you can probably reason that while, yes, they were wasting money and wasting money isn’t good, finding this out cauterized the wound and prevented further damage. But how did the client react?

He freaked out.

The client, instead of listening to the suggestions, fired back with accusations of how the data could just not be true. In essence, the client was presented facts that did not align with is world view, so instead of adjusting them, he bolstered his previous beliefs.

This is the exact definition of the Backfire Effect: “When people react to disconfirming evidence by strengthening their beliefs.” By the way, you’ve totally run into the Backfire Effect in real life if you’ve ever talked politics with someone. You’ve seen comments sections on articles that completely embody the Backfire Effect. It’s looks so painful when it’s not happening to you, but we all fall for it sometimes.

How else can this affect your growth?

At a company with a true culture of experimentation, importance is not placed on the value of an individual idea, but rather a disciplined process. When a company places importance on expertise and ideas, it incentivizes people to hold on to them too strongly in attempt to defend their ego.

In practice, it looks like this: Someone suggests an A/B test. They’re heavily invested in their own idea, and thus the outcome. The outcome is not what they thought. Instead of believing the data, they start to deconstruct the data and find all sorts of cracks in how the data was collected, how the test was set up, etc.

Don’t fall victim to the Backfire Effect. It stifles the truth in favor of ego defense. View opinions and ideas as hypotheses, and view contradicting evidence as new knowledge (not an attack on your opinion).

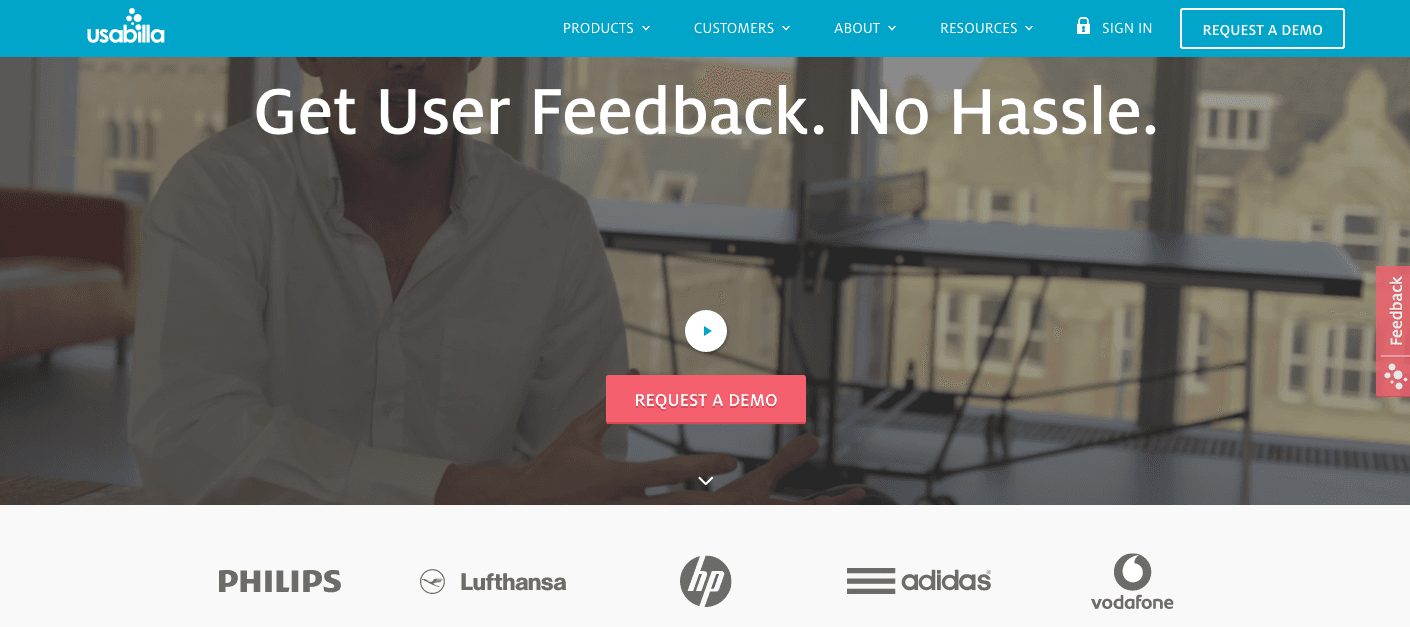

5.) Bandwagon Effect

The Bandwagon Effect is the “tendency to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same.” It’s highly related to groupthink and herd behavior.

You may know it in its positive context, social proof. Lots of companies use social proof to invoke herd mentality and nudge users to action. After all, nobody wants to eat in the empty restaurant or go to the empty club. We can imply that because Adidas uses Usabilla, we can trust them, too:

But our tendency to blindly follow others has disastrous effects in meeting rooms and within organizational contexts.

Image Source

Essentially, people will rally around a cause, an idea, a candidate, a variation, or a strategy simply because it is popular. If your organization is conducive for the other biases listed above, the effect is compounded. You get an incompetent but confident executive (DK effect) that seeks only information that confirms his worldview (confirmation bias) and uses storytelling to sway others (narrative fallacy) to form a herd, then it would take a strong argument to say you’re ‘data-driven’

Bandwagon effect is probably the hardest bias to avoid, as it’s human nature to follow what is popular, especially in uncertain environments (startups).

Other than mitigating the risks of the other biases above, here are a few recommendations that may help you break up the conformity:

- Don’t emphasize ideas and expertise. It creates the incentive to persuade others to the idea itself, not the process and the experiment.

- Anonymize ideas. In Nudge, Richard Thaler wrote “social scientists generally find less conformity, in the same circumstances as Asch’s experiments, when people are asked to give anonymous answers. People become more likely to conform when they know that other people will see what they have to say.”

- If you associate with marketers who believe changing a button color will dramatically impact conversions, you’re more likely to believe that changing a button color will dramatically impact conversions as well. Be aware of who might be influencing your tests, without your knowledge.

- All wins are perishable. Continuously update your knowledge on optimization, analytics, and growth. Realize it’s an ongoing process.

Conclusion

Cognitive biases are unavoidable. They creep up unconsciously, and they erode the rationality that we think we embody. Just by knowing that they exist, you can mitigate the risk that biases pose on your analytics, optimization, and growth. Most of it is organizational. After all, the numbers are there to inform decision making. Humans still must make the decisions – and that’s where all the nuance exists. Focus some of your attention on de-fogging the decision making process, and the numbers will provide much greater value.

Alex Birkett

Growth Marketer, HubSpot

Alex Birkett is a Growth Marketing Marketer at HubSpot. Formerly, he worked as a growth marketer at ConversionXL. He moved to Austin, Texas after graduating from the University of Wisconsin.

More from Alex