Airtable’s Chief Product Officer on Building Products that Amplify Our Creative Potential

We’re thrilled to feature this guest post from Andrew Ofstad, Chief Product Officer at Airtable.

Humans are preternaturally skilled at amplifying their inherent abilities through tools. We chisel rocks, we ride bicycles, we use computers.

Most products out there today, however, aren’t working to expand or amplify the range of our abilities or creative potential. They’re providing convenience. They’re allowing you to do the same things you were doing before with greater ease:

- Text-based chatbots and voice-based assistants make it easier to check sports scores or the weather report

- Mobile apps make it **easier **to call a cab or get groceries delivered to your apartment

- Social media makes it **easier **to remember your friends’ birthdays and wish them well

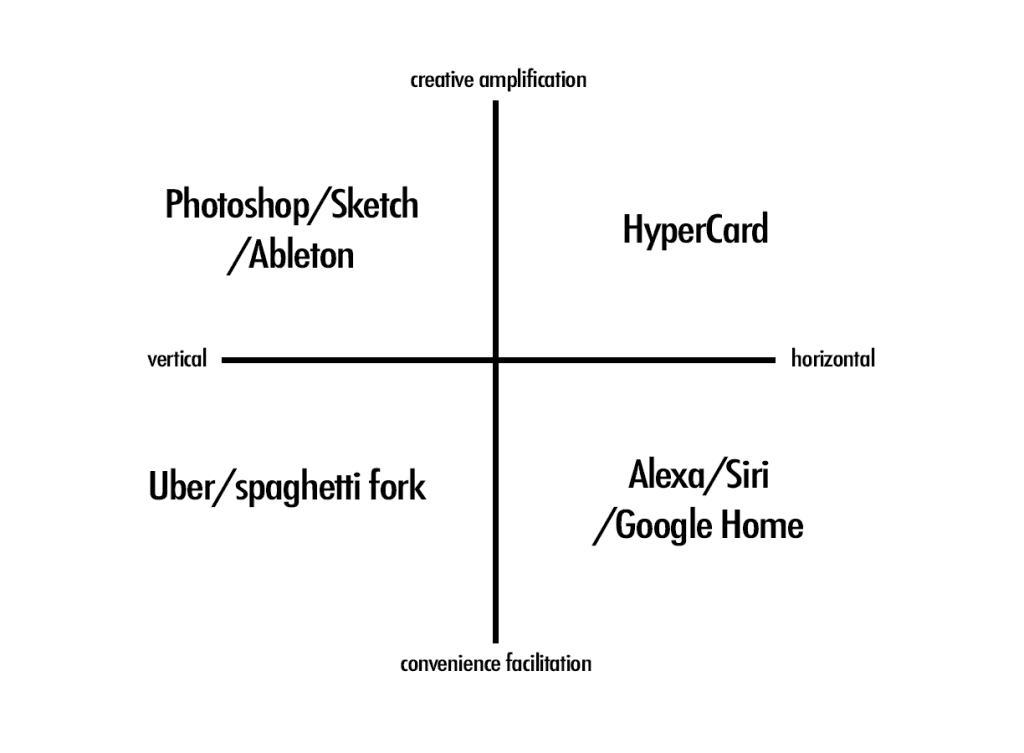

Most apps out there, in other words, are basically battery-powered spaghetti forks. They solve very tightly-scoped problems. And do we really want to download a new app every time we eat a different kind of food? Some products take on one main use case but **amplify **human potential rather than just making a task easier. These include tools like Photoshop, Ableton, Sketch, CAD, Final Cut, and others. If you’re just putting together a quick video, Final Cut might not make it easier—but it does make it possible for millions to create far more complex and advanced films than they could before.

Ableton was built by two German techno DJs to make it easier to run through the complex series of loops and samples that made up one of their average live shows. Now, it’s credited with fueling the 2000s music festival craze—as “suddenly everyone who’s producing electronic music has a clear path how to bring [it] on stage.” Every product falls somewhere on the spectrum between convenience facilitation and creative amplification, and between horizontal (many use cases) and vertical (few use cases). Most fall in the category of vertical & the convenience facilitating: Freeing up time is great. The tools we’ve built to do it are great. But where we truly have a need today is for tools at the creative end of the spectrum—where our tools don’t just save us time or money but help us tackle more ambitious problems.

An example of a product with superb creative amplification

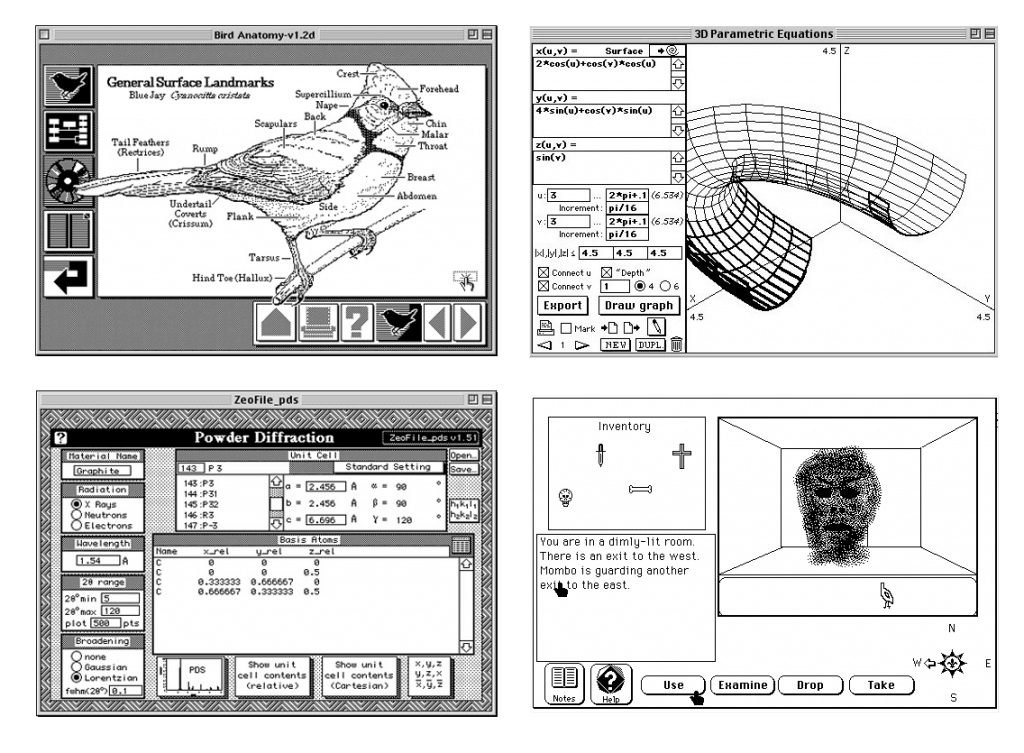

In the top left corner of the above 2×2, at the intersection of horizontal utility and creative amplification, we have HyperCard. This quadrant is the area where we see the least product innovation today and where we have perhaps the greatest need for it. Described by creator Bill Atkinson as a software “erector set,” HyperCard was a precursor to the web itself, released with an early version of the Macintosh OS. It gave users a set of tools for building interactive applications based on cards, records, a programming language called HyperTalk, and a basic database. According to records kept by the Victoria Museum, it was used—just in Melbourne alone— as:

- a stack of multiple choice test questions

- a method for assembling, storing and delivering teaching materials that included graphs from Excel

- making class KeyNote-like presentations and handouts for students

- a calculator that included a variety of mathematical functions and graphing capabilities

- computer aided instruction in the sciences incorporating animation and sound

- visualization of fractals

- Geographical Information System tutorial

- oil-spill modelling

- literacy development application

- road safety booklet

- a database front-end to an Oracle database

- a database in toxicology

- selecting and playing tracks on a videodisk

- an interactive educational presentation showing jobs in the wool industry

- educational interactive games ‘Flowers of Crystal’ and ‘Granny’s Garden’

- part of an application called ‘Beach Trails’ – exploring the local sea shore and shells.

- TTAPS (‘Touch Typing – a Program for Schools’)

In a “jobs to be done” driven development culture, a product like HyperCard would have to be evaluated against all of the above jobs. But these weren’t utilities that were programmed into HyperCard from the start. There was no one ideal distinct user type for HyperCard, no ideal use case. There was a basic set of applications that users could tap into from day one, but then there was just a range of infinite possibilities built on records and cards.

HyperCard found applications in the educational, entertainment, scientific, and many other industries.

HyperCard wasn’t a tool built to fill a specific need, but an emergent product that opened up and let users define it as they went along. It was a piece of software that, in the words of Alan Kay, sought to “teach the user deeper ideas about how the application is structured” and then “let the user open the hood” so they can fit it to their specific needs.

A feature roadmap for building emergent products

When you’re building products on the web today, the typical path is to build for a specific use case and to seek to reduce some element of friction, whether time or energy. Today, however, we have a glut of such tools. What we need are more emergent tools, more creative kits, more indeterminate, sandboxed applications that allow users to be creative and explore. Humans are a massive source of creative potential. When our tools don’t acknowledge that, we aren’t doing all we can to bring that potential to bear. Tim O’Reilly said, “don’t replace people. Augment them.”

Here are some ways to start thinking about building products that augment creative potential rather than replace:

- **Start with building blocks, not use cases. **We know from programs like HyperCard, and toys like Legos, and networks like Twitter, that systems are capable of exhibiting quite complex patterns of emergent behavior when they’re set up with the right building blocks. You don’t need a complex roadmap to achieve a powerful end result.

- **Power progress through small wins. **Users will make more progress if they’re motivated. As they learn the ins and outs of a product, recognize their achievements and point them towards deeper and deeper ideas about “how the application is structured.”

- **Allow users to make mistakes. **The products that best encourage creativity do it by making mistakes feel like non-mistakes. Some products build sandbox modes so you can emulate all of its features without lasting consequences in a special environment. Just as crucial is making sure that users can “undo” most changes they make with ease—if people are afraid to experiment, they won’t.

An open-ended product is hard to build. You have to make very conscious decisions about what aspects to keep away from the user and what aspects to expose to them for manipulation. This is also, in many ways, an approach at odds with current trends in technology. The potential for human augmentation with technology, however, is far from tapped—and anyone building product today would be wise to consider how they can better harness the creativity and imagination of their users.

Editor’s note: This post is part of our Product Innovator Series that explores what it takes for businesses to survive and thrive in the product-led era.

Photo by Leonard von Bibra on Unsplash

Andrew Ofstad

Co-founder and CPO, Airtable

Andrew Ofstad is the co-founder and Chief Product Officer of Airtable. Previously, he lead the redesign of Google's flagship Maps product, and before that was a product manager for Android. Andrew studied Electrical Engineering and Economics at Duke after a childhood in rural Montana.

More from Andrew