Customer Attrition Analysis and Optimization

Learn how to calculate customer and logo attrition, why customer attrition matters, common causes of it, and how to improve attrition rates.

Customer attrition is one of the key predictors of product success—and ultimately, company success. After all, keeping customers happy and engaged with the product over the long run is a great way to strengthen profits and build up customer lifetime value. In this guide, we dive deep into customer attrition and provide you with actionable next steps and recommendations.

Key Takeaways

- Customer attrition, also known as customer churn, is when a customer stops using your product.

- Customer attrition impacts your company’s brand, revenue, and profits.

- Key factors that drive customer attrition include:

- misaligned marketing

- onboarding friction

- competitive action

- end-to-end customer experience gaps

- To counteract attrition, product managers should focus on removing adoption friction and creating positive product usage habits for their customers.

- Product marketers should focus on amplifying the value proposition of the product.

- For B2B products, customer success managers and account managers have a crucial role to play in improving customer attrition rates.

What Is Customer Attrition?

Before we can discuss customer attrition, we first need to define what exactly a customer is.

A customer is any user of your product, whether they’re paying money (e.g. for ecommerce products, gaming products, subscription products, etc.) or whether they’re investing their own time (e.g. for social media products, productivity products, etc.).

The reason why we define customers this way is because our product’s users are real people with real needs. Simply calling them “users” fails to capture the fact that their goal is not to use our product.

Rather, their goal is to satisfy a particular need that they have, and they’ve “hired” our product to make progress towards that goal.

So, now that we’ve defined who customers are, we can break down what customer attrition is.

Attrition is what happens when customers stop using your product. You might have heard the term “churn” before; churn and attrition are the same phenomenon.

You may have also heard of “retention” before. Retention is the proportion of customers that have stayed loyal and active on your product.

Attrition and retention are two sides of the same coin. That is, for every customer you retain, that’s a customer that you haven’t lost.

And on the flip side, for every customer that attrites, that’s a customer that you failed to retain. In other words, your attrition rate plus your retention rate should sum up to 100%.

Calculating Customer Attrition

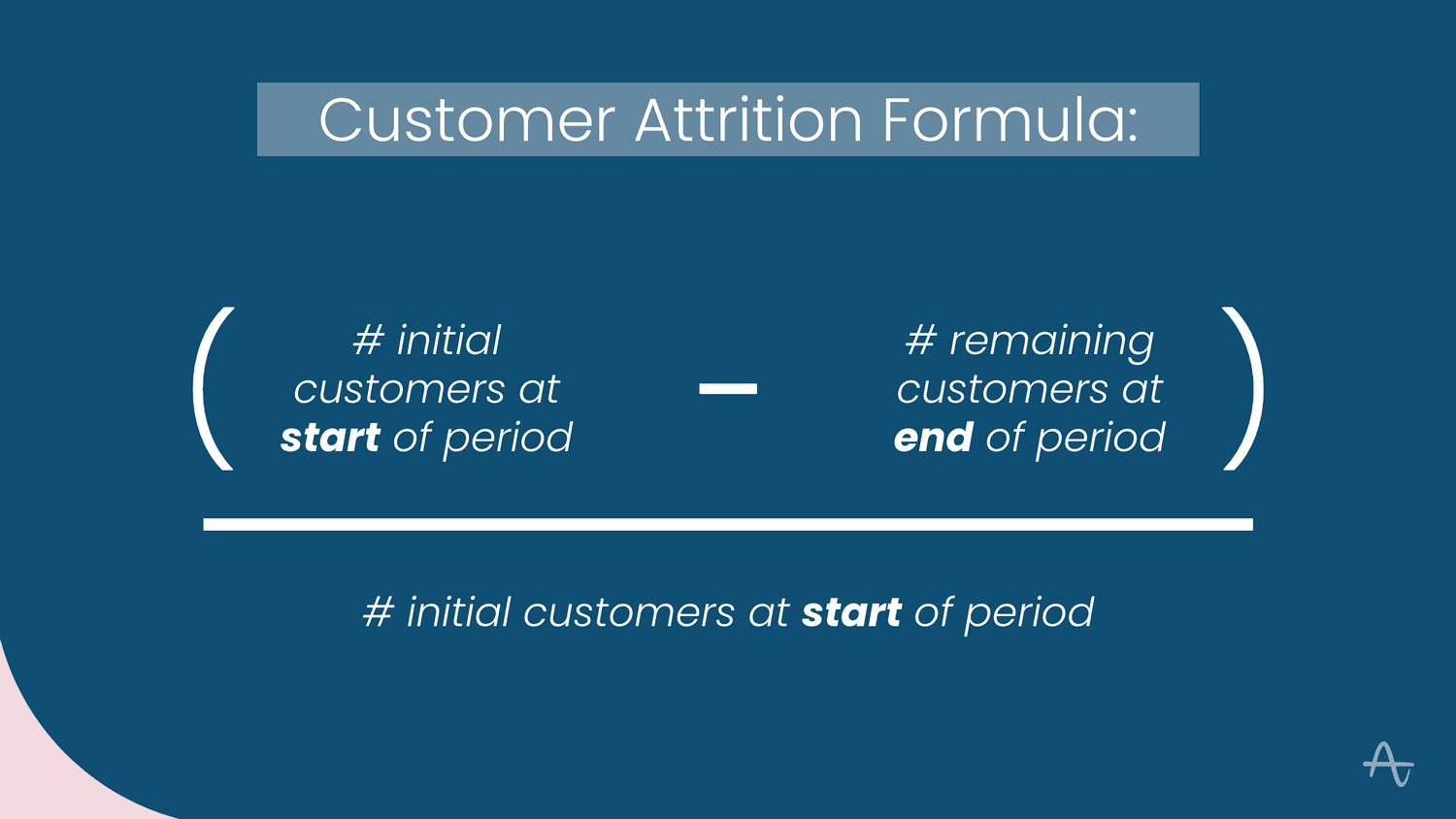

The formula for attrition is this:

Customer attrition = (“# initial customers at start of period” – “# remaining customers at end of period”) / (“# initial customers at start of period”)

In other words, attrition is time-bound. Weekly attrition rates and monthly attrition rates will give you different numbers because you’re looking at different periods of time.

Therefore, monthly attrition rates will typically be higher than weekly attrition rates, as more time has passed, which means more opportunities for customers to stop using your product.

Furthermore, attrition rates can’t be negative; the theoretical lowest possible attrition rate is 0%.

We want to exclude customers who have been added to the product during this timeframe, because that doesn’t tell us how well we’re retaining our previous customers.

Why Customer Attrition Is Powerful to Measure

Why is the customer attrition formula so powerful? It’s because we’re no longer looking at a simple “total customer count” over time. The attrition rate shows you whether you’ve kept your customers over time.

Here’s why total customer count is deceptive. Total customer count includes newly added customers, whereas customer attrition excludes newly added customers.

To bring this concept to life: Imagine that you had a product where your total customer count increased from 10,000 customers to 15,000 customers over the course of one month.

At a surface level, that looks like a good result!

But, perhaps your marketing efforts had actually brought in 7,000 new customers, whereas 2,000 of your current customers stopped using the product.

You wouldn’t be able to gain that insight if you solely looked at total customer count.

But, if we use the customer attrition formula, a different picture emerges. We had 10,000 customers at the start, and 2,000 of this initial 10,000 stopped using the product, so we have only 8,000 remaining customers.

Note that we’ve excluded the 7,000 newly added customers during this timeframe.

From here, we can then see that our customer attrition rate is (10,000 initial customers – 8,000 remaining customers) / (10,000 initial customers) = 20%.

To put this into perspective: for every five customers that we serve, one of them is no longer using the product after one month.

With such a high attrition rate, we need to prioritize immediate action.

Why Does Customer Attrition Matter?

Customer attrition is a top priority not just for product managers and marketers, but also for executive leaders and investors.

The negative impact of customer attrition can be broken out into the following components:

- Brand damage

- Loss of future revenue

- Loss of profits

Customer Attrition Causes Brand Damage

First, unhappy customers can damage your brand. An unhappy customer is far more likely to be vocal about their displeasure, whereas most happy customers won’t proactively share about their good experiences.

Attrited customers are likely to share about their negative experiences in their private day-to-day conversations as well as publicly on social media. Prospective customers take negative feedback from current customers seriously—a single negative review can outweigh a dozen positive reviews.

Customer Attrition Leads to Revenue Loss

On top of that, when you lose a customer, you’re not just losing immediate revenue from them, but you’re also losing all future revenue that you could have gained from them. That includes opportunities for renewal and for upsell.

Remember, customers are human beings who have a multitude of needs. When customers successfully adopt one product from one company, they’re much more likely to adopt additional products from that same company to solve other adjacent pains.

This fact is a double-edged sword: as soon as the company drops the ball for one of their products, customers will question its other products too.

Customer Attrition Drives Thinner Margins

Finally, acquiring new customers is significantly more expensive than retaining current customers.

After all, new customers don’t know what the value proposition of the product is, whereas current customers are already bought into the premise that your product is valuable to them.

That’s why a “growth at all costs” strategy simply doesn’t work in the long run. If the majority of your revenue growth is coming from new customers rather than current customers, then customer acquisition costs will eat away at your profits. At a company level, retention is a stronger predictor of long-term profitability than top-line growth is.

So now we understand why customer attrition should be top-of-mind for product managers, product marketers, and executive leaders. But why exactly does customer attrition happen?

Common Causes of Customer Attrition

Why do customers stop using products? Here are four key factors that we’ve observed in our product management coaching practice at Product Teacher:

- Customers are disappointed by the ROI of the product.

- Customers struggled to adopt the product.

- Customers found competitors with better ROI.

- Customers felt undervalued by the company.

Let’s dive into each factor.

1. Insufficient ROI

First, customers might have expected a particular return on investment that didn’t pan out. That is, the costs of your product are higher than they expected, or the benefits that they actually received were lower than they expected.

That’s why it’s crucial to set the right expectations upfront, and then to meet or exceed them. If your product’s marketing positions it as a “cure all” for a broad problem area, but customers find out that it only resolves a particular niche pain rather than the entire problem area, then they will stop using your product.

Even if your product is free, your product’s users are still customers. After all, you won’t be able to monetize the product (e.g. through advertising, sponsorship, or data reselling) unless you solve the needs of your customers.

And, just because your product is free doesn’t mean that customers aren’t picky. Time investment is a type of cost too—so, your product must yield more value than their time is worth, or else they’ll decide to invest their time elsewhere instead.

2. Customer Adoption Challenges

Second, customers might have struggled to adopt the product. Every product must displace previous habits.

If the value of adopting a product (e.g. a social media platform) isn’t worth the cost of adopting it (e.g. learning how to use it and creating content on the platform), then customers will attrite.

As an example, TikTok may not retain elderly customers as well as younger customers, since the cost of adopting TikTok is significantly higher than the benefit they could expect to reap.

So, product managers and marketers can’t solely look at the product functionality itself, or the market-facing positioning of the product.

They must consider whether they’ve targeted the right kinds of customers, and they must also consider the processes that customers go through when adopting the product into their day-to-day lives.

As another example, consider Duolingo, the language learning product. It does an excellent job in onboarding new customers and keeping them engaged with rewards and a sense of progress. Without these core pillars, Duolingo likely would not have taken market share from more traditional language learning programs, such as in-person language tutors.

Because Duolingo has kept the customer adoption journey front and center, they’re able to prevent significant customer attrition, with an impressive 55% next-day retention rate.

3. Competitive Alternatives

Third, customers might find that competitors have presented them with higher ROI versus your product. After all, customers aren’t solely looking at your product offerings. They’re constantly evaluating alternatives on the market and deciding whether to stay committed to your product or whether to leverage other solutions instead.

Surprisingly, ROI assessments are not as simple as “current product benefits” versus “current product costs.” Customers are also evaluating the future ROI that your product promises them—and this fact is particularly crucial for enterprise B2B products.

Most product managers and product marketers have a clear grasp of the present ROI of their product offerings. They understand that customers seek to find solutions to current pain points, and that they’re deciding whether or not to “hire” the product to solve the pain.

But future ROI is a significantly overlooked component of the product value proposition. When customers assess future ROI, they’re predicting what your product will do in the future, in terms of roadmap, development velocity, benefits, and costs.

As an example, consider a security leak for a particular product. A specific customer might not experience a change in current ROI—that is, none of their information leaked, and so their current day-to-day lives aren’t affected.

But, their perception of future ROI is now significantly bleaker than it used to be. They’re worried that their information will eventually leak, and so they’ll start to seriously consider alternatives.

Even putting aside security leaks, if your roadmap does not proactively stay one step ahead of your customers’ evolving needs, you may find that customers will swap to competitors that are less mature today but promise to be significantly more powerful tomorrow.

Especially for enterprise B2B products, it’s common for customers to churn due to a lower-than-expected future ROI. What this means: they might find your current product delightful, but they may be concerned that your product is headed in a different direction than where they’re headed.

That’s why they’ll part ways even though your current product serves their current needs—it’s because your future product won’t serve their future needs.

4. Feeling Undervalued

And finally, if the customer feels undervalued, they’ll also stop using your product.

For example, if your customer support team doesn’t resolve customer issues promptly, your customer will likely attrite.

Similarly, for B2B products, if customer success and account management isn’t providing your customer accounts with a game plan for how to grow alongside their implementation of your product, they’ll seriously consider terminating the relationship. And, if your customer feels like the product / design / engineering team isn’t taking their feedback seriously, then they’ll also look for other providers.

While customers evaluate products based on return on investment, we have to remember that a key promised benefit of any product is its emotional benefit. So, keep in mind that if your product gives customers negative emotions, then they’ll switch to another product that gives them positive emotions.

In fact, positive customer emotion is a crucial aspect of customer retention. Even if a rational side-by-side product comparison demonstrates that your product is less mature or less fully featured than competitors, if your product elicits positive emotions from customers, then they’ll stick with your product over time.

How Customer Attrition Feeds into Logo Attrition in B2B

Business-to-business (B2B) products work differently from business-to-consumer (B2C) products. Most B2B products will have multiple customers within a logo, or organization. For example, an Amplitude logo—an organization that purchased Amplitude—might have 100+ customer seats within that account.

Even if a single customer stops using a B2B product, the overall logo doesn’t necessarily churn. So why should we pay close attention to customer attrition in B2B products as well?

That’s because customer attrition is a leading indicator of logo, or account, attrition. The more customers within a logo who attrite, the less value the logo is deriving from your product. And the less value they’re getting from your product, the less likely they are to renew with your product.

And, the opposite is true as well. If customers are fiercely loyal to your product offerings and they find tons of value using your product on a day-to-day basis, then the logo is unlikely to terminate their contract. In fact, they’re likely open to learning more about how your product portfolio can serve their adjacent needs as well, given how well you’ve served them.

With this lens of logo attrition vs. customer attrition, we can more clearly define how product management and product marketing fit into each metric.

As a product manager, you have more levers to prevent customer attrition at a person-by-person level.

And, as a product marketer, you have more levers to prevent logo attrition at an account level.

But before we continue, let’s take a step back. Is all attrition necessarily bad for your organization?

Why Not All Customer Attrition Is Bad

As product managers, product marketers, and executive leaders, we should focus on serving customer segments where we can provide the most value.

While this statement isn’t controversial, the contrapositive of this statement can be quite controversial: “we should not attempt to serve customer segments where we can’t provide a lot of value.”

As an example, products that are built to serve nonprofits are rarely good fits for for-profit companies without significant rework. As another example, products that are built to serve enterprises are typically not going to fit out-of-the-box for SMB customers.

Yet when it comes to customer attrition, many teams seek to retain every single customer, even though some customers are simply not good fits. We shouldn’t do this, because trying to retain a low-fit customer harms both the customer and your organization.

If the product was never going to be a good fit, attempting to save these customers is not a valuable use of time. Due to the lack of product/market fit for these customer segments, we should not commit our valuable and constrained resources here.

Instead, as product teams, our focus should be on “regrettable” attrition. That is, we should pay special attention to customers who stopped using the product when it clearly would have been a good fit for their needs.

We now have a working definition of what customer attrition is. Let’s now talk about how to instrument our customer attrition metrics.

Tracking Customer Attrition Rate

As a quick reminder, here’s the formula again for customer attrition rates:

(“# initial customers at start of period” – “# remaining customers at end of period”) / (“# initial customers at start of period”)

But, this definition obscures a crucial detail. We need to define which customers are actually actively using the product!

For both “customers at the start” and “customers at the end,” we need to qualify each metric by identifying “qualifying activity” that demonstrates that they’re getting value out of your product. In other words, we need to decide what makes any particular customer an “active customer” in terms of in-product usage.

I make this clarification because logging into the product is not enough to drive real customer value. As an example, let’s say that a customer receives a notification email from Pinterest to look at newly posted pins from people that they follow.

If that customer logs in and then finds out that those pins don’t actually interest them, they’re not going to click into any more pins, nor are they going to save any pins to their boards. We haven’t actually created value for them, and so we shouldn’t be counting this customer as “active.”

Hopefully, this example clearly illustrates why we need to thoughtfully define active customers, and why login count is simply not enough to drive meaningful action for product managers or product marketers.

When we think about “which activities drive customer value,” we’re typically interested in specific workflows being completed.

For example, logging into Salesforce is probably not a good definition of activity, but creating a lead in Salesforce is a good indicator that the product is providing customer value.

Or, let’s consider YouTube. Landing on the homepage itself is likely not a good proxy of customer value, but clicking into a recommended video and watching it for at least 1 minute is probably a good indicator of customer value.

Once we define which activities and workflows qualify customers as active ones, we’ll want to work alongside engineering and data analytics teams to track these particular actions. We’ll want to capture which users took which actions of interest, on which dates.

From here, we now have clarity into which customers are active at the start of the period, and how many of those customers have stayed active at the end of the period. We can use this information to calculate a baseline attrition rate.

Now, as we continue to make changes in product functionality and product positioning, we can observe the impact to this baseline attrition rate.

For our readers who are familiar with MAU (monthly active users) and WAU (weekly active users), attrition is simply the opposite of retention. So, we want to drive retention upwards and drive retention downwards through our ongoing iterations and refinements!

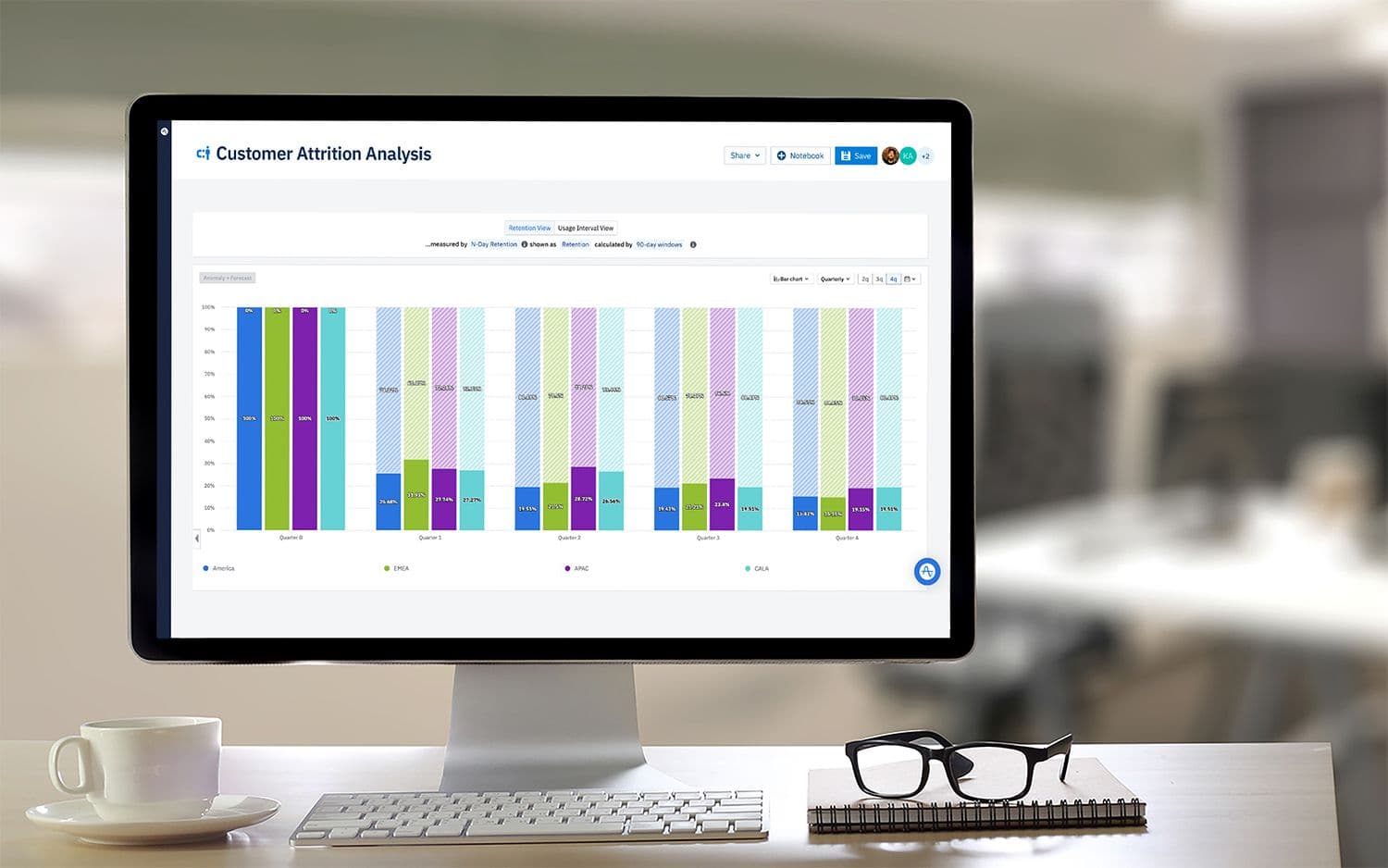

[Learn how to calculate customer churn/attrition rate in Amplitude.]

Analyzing Customer Attrition Rate

Let’s dive a bit deeper into how we can further analyze customer attrition rates.

One of the most powerful techniques at our disposal is cohort analysis. Cohort analysis just means that we’ll break up our customers into different groups, and we’ll analyze how each group is performing versus one another.

One easy-to-run cohort analysis is to cohort by customer onboarding date. That is, we want to group together customers who signed up for the product at around the same time.

The underlying assumption here is that customers who sign up at similar times are experiencing similar product functionality. After all, products evolve quickly, so a customer who signs up in February will have a significantly different experience from one who signs up in August.

If we group our customers by “onboarding week,” we’ll have 52 different groups over the course of a calendar year. We can track how attrition impacts each group as the weeks go by. I’ve written up a separate deep dive on cohort analysis that you can read here.

Another kind of cohort analysis you can run is behavioral segmentation. Instead of grouping customers by “which version of the product did they see when they joined us,” we can group them by the kinds of behaviors that they exhibit in our product.

As an example, let’s say that we hypothesize that a newly released feature should help alleviate customer attrition. To validate or invalidate this hypothesis, what we can do is group customers by “how much they use this new feature.” You can use buckets like these:

- Highly active: top quartile of feature usage

- Moderately active: next two quartiles of feature usage

- Infrequently active: bottom quartile of feature usage

If the hypothesis holds true, then we should see that the “highly active” customers of this feature have lower attrition rates in the overall product, and that “infrequently active” customers of this feature have higher attrition rates in the overall product.

And if this hypothesis doesn’t hold true, then we shouldn’t see a significant difference in attrition rates based on this behavioral segmentation.

Or, counterintuitively, we might even find that the reverse hypothesis is true: perhaps the newly released feature is actually creating too much customer confusion, leading to a negative impact on attrition.

In that case, what we’d observe is that “highly active” customers of this feature have higher attrition rates in the overall products versus other customer behavioral segments—and that would be a signal that we should probably roll back the feature ASAP.

If you happen to be tackling B2B cohort analyses specifically, we can also use different kinds of customer attributes to analyze customer attrition.

I recommend segmenting customers by the following attributes as an initial exploration:

- Size of logo

- Logo vertical

- Enabled feature set for the customer user

- Customer user role (e.g. basic vs. advanced vs. admin)

And, depending on the specifics of your particular customer base, you can further refine these segmentations to account for unique attributes that other kinds of companies may not be actively analyzing.

So, now we have some analytical insight into customer attrition rate. What actions should we take to optimize customer attrition?

Optimizing Customer Attrition Rate

Something that we should keep in mind as we look to optimize customer attrition rates: prevention is more valuable than attempting to resurrect (a.k.a. “save”) customers when they’re already in the process of attriting.

We have the least leverage once a customer has already decided to stop using their product. Their minds are set, and they are already disaffected with your offerings. So, they’re not likely going to keep an open mind when you try to convince them to continue using your product.

Paradoxically, we have the most leverage over customer attrition when customers are still actively using our products. So, we need to approach the problem from the lens of prevention rather than from the lens of resurrection.

Here are some ways for us to influence customer attrition:

- Run customer interviews to dive into pain points and validate potential solutions.

- Conduct A/B tests within the product to reduce UX friction.

- Partner with your customer support team to ease customer adoption by providing product trainings and walkthroughs.

As a last note on optimizing customer attrition rates: while analytics is valuable for telling us “what’s happening with customers” and “how many customers are impacted,” we can only truly understand the motivations behind customer behaviors by directly speaking to customers themselves. Once we understand their motivations, we can then refine our product functionality and our product positioning to better serve their needs.

We now have techniques at our disposal to optimize customer attrition. But, for those of us working with B2B products, how do we track, analyze, and optimize logo attrition rates?

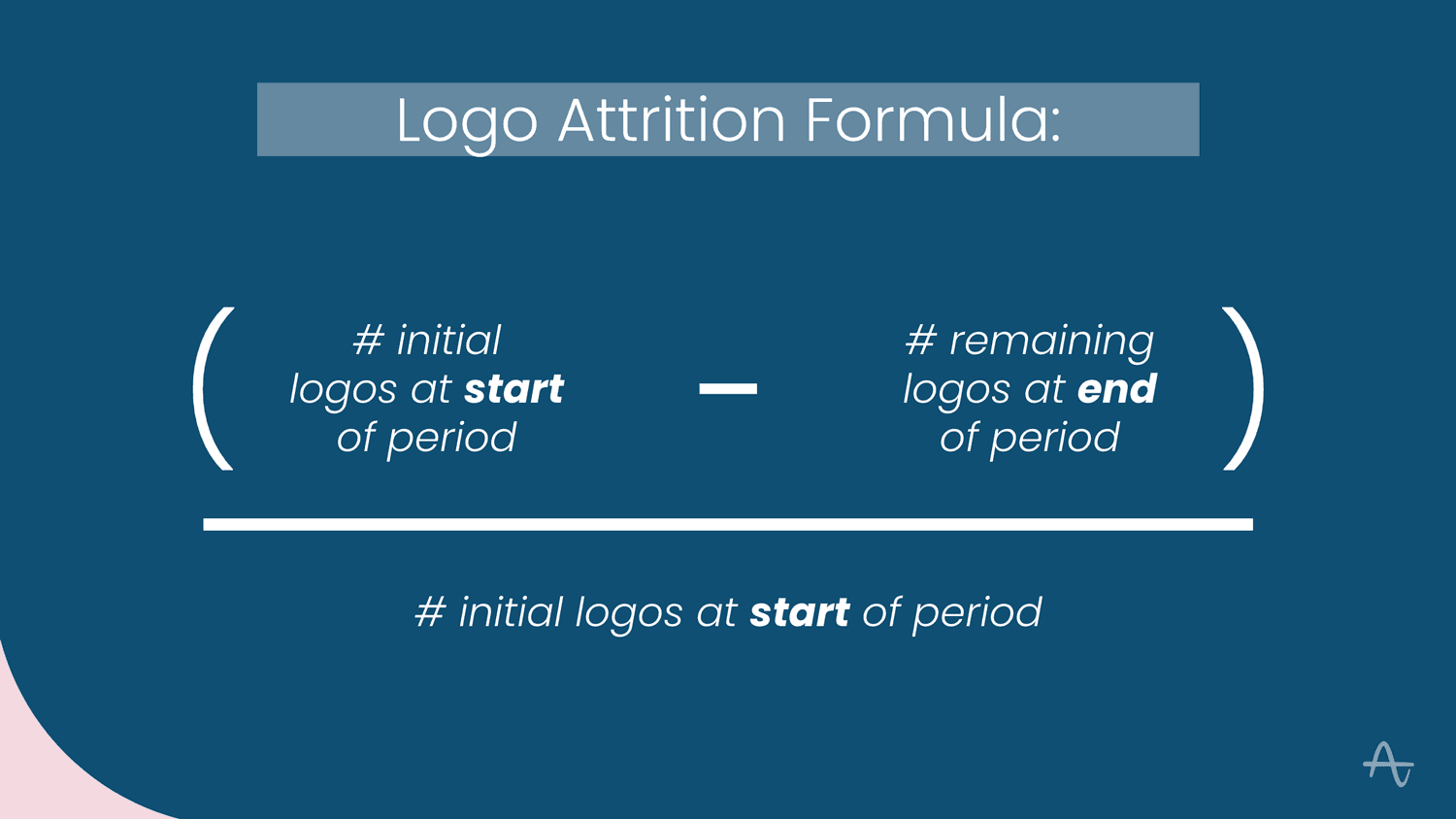

Tracking Logo Attrition Rate

Let’s update our attrition rate formula to account for logos instead:

Logo attrition = (“# initial logos at start of period” – “# remaining logos at end of period”) / (“# initial logos at start of period”)

Thankfully, tracking whether a logo is active or not is significantly easier than tracking whether a given customer is active or not. Logos are active if they have an active contract with you and are paying for your products. If they don’t, then they’re not considered active.

Tracking active logos is also relatively straightforward. If your organization currently uses a CRM (customer relationship management system), then the CRM will provide you with logo data as part of its core functionality.

If you’re at an early stage organization that doesn’t use CRMs yet, no worries! Even a simple spreadsheet will do the trick when it comes to identifying which logos are active in which months.

To track attrition rate at a logo level, run regular reporting. Weekly reports won’t make sense for logos, as logos typically sign monthly, quarterly, or annual contracts. So, you can run monthly or quarterly reports for logo attrition instead.

As a reminder, logo attrition rates tend not to shift dramatically due to new product releases; instead, they tend to change due to product positioning changes or product pricing changes.

Analyzing Logo Attrition Rate

Analyzing logo attrition rate is similar to analyzing customer attrition rate. When a logo has decided to terminate their contract with your organization, conduct an exit interview with them if they’re open to providing feedback. In that exit interview, you’ll want to understand their reasons for terminating, and whether there’s anything that your organization can do to change their mind.

As you gather this qualitative feedback at a logo-by-logo level, you’ll start to identify recurring themes that are driving attrition. These themes are strong starting points for coming up with initiatives that may help with reducing logo attrition.

For a more fine-grained analysis, you can further split out logos by logo attributes, such as:

- Size of logo (e.g. number of employees or annual revenue)

- Vertical / industry

- Geography

Partnering with Account Management to Reduce Logo Attrition Rate

As a reminder, preventing logo attrition is far more valuable than attempting to save logos as they work through the termination process. So, we’ll want to partner with customer success teams and account management teams as early as possible for their respective logo accounts.

We never want to have “silent attrition” where logos decline to share their reasons for why they’ve decided to stop using our product offerings. Even if we ultimately identify that the logo wasn’t a good initial fit for our products, we still need to gather that information to inform our future positioning in the market.

To get ahead of silent attrition, customer success teams should run proactive quarterly business reviews (a.k.a. QBRs) with logo-side executives. These reviews provide a space for logos to share their feedback, providing us with early insight into potential likelihood for attrition, as well as the underlying reason that drives the potential attrition risk.

Furthermore, we should plan ahead for contract renewals for each logo that we aim to retain. After all, contract renewal dates aren’t surprises—they’re already written into the contract itself. So, we should never be caught unprepared with contract renewal conversations with logos.

In the book The Startup’s Guide to Customer Success, the author Jennifer Chiang recommends on page 238 that customer success managers (CSMs) should proactively share the logo’s current product usage metrics as part of renewal conversations, ideally 60-90 days ahead of the actual contract renewal date.

Furthermore, customer success managers should cover the upcoming product roadmap to share insights into potential future ROI that customers can expect to reap as the product continues to evolve and mature.

As the renewal process requires that CSMs provide both quantitative analytics and qualitative insights & trends to customer executives, product managers and product marketers both have a role to play.

Product marketers should listen into the conversation to better understand any potential gaps between customer expectations versus actual customer ROI. They’ll learn which parts of the value proposition are resonating and which parts have fallen flat, and they’ll have the chance to surface relevant customer case studies during the renewal process to convince logos to stick with the product.

Product managers should engage to understand which aspects of the product have provided outsized value versus which aspects failed to fully deliver on its promised value. By listening to the logo’s priorities and upcoming roadmap, product managers can better calibrate their own understanding of “which product initiatives will unlock the most future customer ROI,” enabling them to scope and prioritize the right areas of investment.

Closing Thoughts

We hope this comprehensive guide has empowered you to take action on addressing customer attrition. You now have an end-to-end playbook for defining, measuring, analyzing, and improving customer attrition.

If you remember only one insight from this deep dive, let it be this one: we must create value for our customers if we want to capture value for our companies.

Whether you are a product manager, a product marketer, a customer success manager, or an executive leader—it’s everyone’s responsibility to help customers successfully onboard onto the product and build long-term habits and behaviors around the usage of your product.

By doing so, we can successfully bring down customer attrition rates, improve customer lifetime value, and grow the profitability and sustainability of our businesses over time.

Clement Kao

Founder, Product Teacher

Clement Kao is Founder of Product Teacher, a product management education company with the mission of creating accessible and effective resources for a global community of product managers, founders, innovators, and entrepreneurs. Product Teacher offers on-demand video courses, career coaching, and corporate training workshops.

More from Clement