3 Product Metric Pitfalls You Need to Avoid

Learn how to create better, more actionable product metrics in this excerpt from "The Insights Driven Product Manager."

In my book, The Insights Driven Product Manager, I cover why it’s important to track less to create more focus and spend more time on extracting true insights from your data.

The next step is to make sure that on the nitty-gritty level, you are tracking what I call “good quality metrics.” This post—an excerpt from chapter 7 of my book—will focus on how to improve the overall quality of your product metrics, how to make them more actionable, and what pitfalls to avoid.

Pitfall #1: Vanity metrics

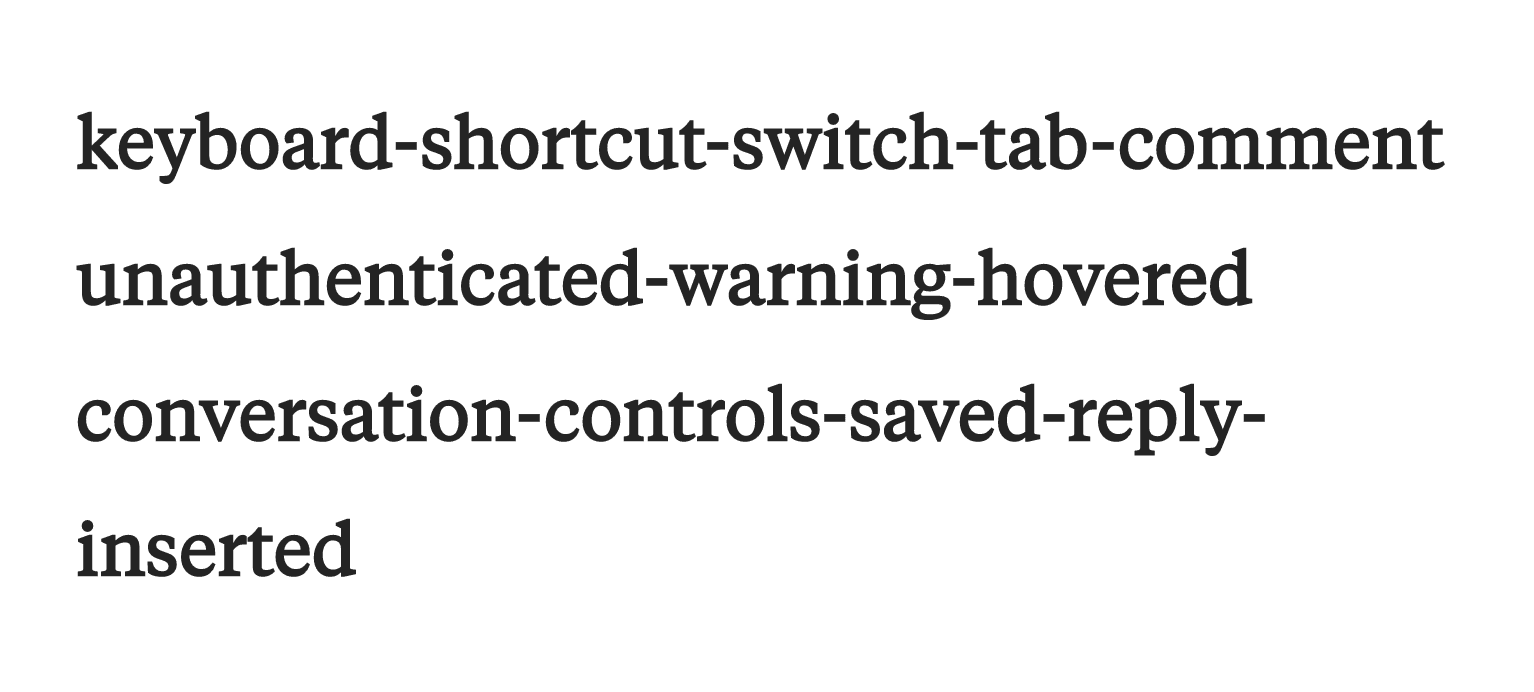

A few years ago I was working on a B2B SaaS product for managing office environments. We just launched the product and started to run our first paid advertising campaigns, so I set up a dashboard that tracked the total number of sign-ups over 30 days:

The numbers seemed to be going up, so we were pretty happy about the momentum.

The problem was that while this graph looked good on presentations, the hard truth was that only 4% of the new sign-ups turned into actual conversions and revenue, and as a result, we did not meet our monthly recurring revenue goals.

It’s a cumulative chart, so the worst case would be that the graph would just plateau if we don’t acquire any new users, but the number can never decrease. It’s a classic example of a vanity metric:

- Looking at this graph made us feel good.

- This metric was especially useful in stakeholder presentations.

- It didn’t give us any insight into whether we were actually doing well, or not.

- Because it didn’t give us any insight, it did not drive us to take action to improve the product or features in any way.

- And despite looking at this metric on a daily basis, it took us two months (by the time all the 30-day trials had finished and churned) to find out that there was an issue.

While one part of the problem was our lack of knowledge on how to measure better metrics at that time, the problem in organizations often lies a lot deeper: most teams or stakeholders are simply not ready to hear the truth from their metrics, so we look for the numbers that make us look good.

In my interview with Crystal Widjaja, CPO at Kumu and writer for Reforge, she summarized beautifully how to view data as a way to capitalize on failures and drive improvements instead:

“When people make mistakes (failed experiment, failed deployment, etc), you’ve already paid that cost. We should think of data as a way to capitalize on mistakes and learn from them. Rather than ‘paying the tuition of the failure’ and firing the individual, use the data insights to tell us WHY it was a failure, learn from it, and leverage it for the next iteration to be 10x better than the first.”

– Crystal Widjaja

In order to get more insights from your data you really need to stop tracking vanity metrics, and instead use data to uncover the truth and drive actual improvements. If you look closely, it’s fascinating how often teams are showing very selective metrics to appease certain stakeholders or make the numbers sound better than they actually are. Watch out for other classic examples of vanity metrics such as:

- Number of page views or visitors

- Number of followers/likes

- Time spent on site (session length)

- Number of downloads

Metrics like page views and session length are still heavily used in website analytics, where the focus is to measure traffic, awareness and initial engagement. They give you some insight on what we call the top of the funnel—the initial acquisition of customers—but not whether customers are actually activating and engaging with the product, which will have a much more meaningful correlation with your wider product and business goals.

How to do it better: to really understand if a metric is good or bad, we need to put numbers into context. At the very minimum, you want to try to compare a number over different time periods, such as comparing your sign-up numbers this month versus the previous month.

Another effective way to make your metrics more useful is to use ratios instead of total numbers. Ratios are inherently comparative. As an example, accountants don’t just look at total revenue, but typically compare the costs of producing a product with the sales they made from it. This way accountants can track their profit margin (a great example of a useful ratio) over time to assess whether the business is healthy.

Examples of better, more comparable metrics:

- % of sign-ups per acquisition channel

- % of sign-ups who completed the full sign-up process

- % of sign-ups who performed a key activation metric

- % of users using the product after 4 weeks

Pitfall #2: Only tracking lagging metrics

A big problem was the amount of time it took us to find out whether we were hitting our conversion goals (or not). The product had a 30-day free trial and our goal was to convert them to paying customers after the end of the trial, so while the first month looked good in terms of sign-ups, we would ultimately only know by the end of the second month how many of those sign-ups converted to paying customers.

This is a classic example of a lagging metric. Lagging metrics report retrospectively on past results. For example, your revenue numbers for the year are lagging metrics like most of your other operational metrics. You only know whether you did well once you have the results.

The real value in tracking user behavior through your product analytics is that you can start to look for earlier indicators than having to wait for your final revenue numbers. If your leading metrics don’t perform well, you have the chance to course-correct before it’s too late. This is why I designed the Holistic Metrics One Pager in chapter five of my book to include both customer behavior and operational metrics, so teams can track a healthy mix of leading and lagging metrics to get the full picture.

One of the most powerful leading metrics is the activation metric. A good activation metric represents the percentage of customers who take a key action of setting up or starting to use the product. Many companies have figured out that if users do a certain action within their product during onboarding, they tend to realize the true value of the product which leads to higher engagement further down the line. Some call this activation step reaching the “aha moment” in their product.

Here are some simple examples of leading activation metrics:

- Social network product: a classic example was Facebook’s first activation metric of adding a minimum of seven friends in 10 days.

- Dashboard aggregation product: the value proposition is to bundle several tools into one view, so you might find that users who add a minimum of two or three tools during onboarding realize the full potential of the product.

- Utility product: your value proposition might be to simplify or digitize a task such as tracking sales conversations in a CRM, so you could track the number of users who complete their first customer entry as quickly as possible as an activation metric.

- Attention product: if your product is centered around entertainment and content you might track users who consumed a certain amount of content in the first week of signing up .

Lagging metrics are not inherently bad, by the way. In fact, they are a critical part of reporting, especially for measuring business metrics such as your financial results. Their advantage is that they represent the final outcomes, the real facts.

Leading metrics on the other hand often include some amount of assumptions like the assumption that a high amount of cold calls every day increases the number of paying users further down the line. As you get more data you should test whether those assumptions are actually true, but even then there is still some uncertainty on whether the activation metric truly caused the increase in retention, or whether other factors contributed to it.

This means leading metrics will never be as accurate as lagging metrics, but they are crucial to getting true insights from your metrics. They allow us to learn from customer behavior and identify early indicators that may change our product decisions to optimize for better business outcomes further down the line. Using the Holistic Metrics One Pager template forces you into tracking both leading and lagging indicators, as well as to think about how those influence each other.

Pitfall #3: Metrics no one understands

When I interview product managers I often hear that analytics knowledge and data insights get hidden away in dark mysterious corners of offices, with event names that no one but a couple of highly specialized analysts understand. Every month those specialists would meet with various product teams in an attempt to share and translate some of their findings.

If we want our product teams and stakeholders to create a shared understanding of our data and discuss improvements to the product collaboratively, we need to actively work on democratizing our data, make sure our metrics are accessible to everyone and easy to understand.

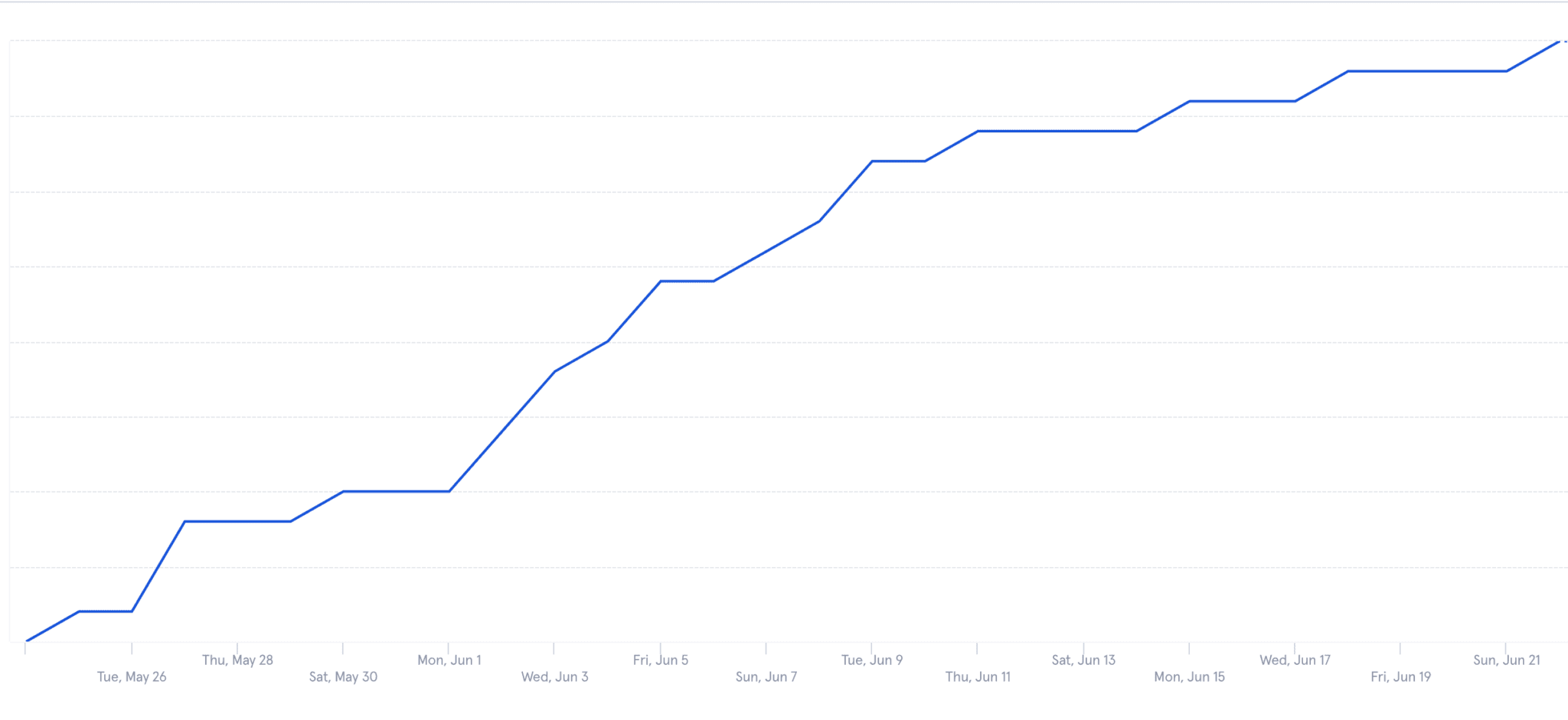

Intercom shared their learnings from doing a massive events clean-up a few years ago. They had around 350 events for their product that kind of looked like this:

Does this look familiar to you?

Intercom shared that they failed a key principle of analytics: they made very little sense to anyone but the analytics team. They redefined and rebuilt their entire naming structure of all their events to introduce better readability as a key step to democratize their product analytics data.

It’s also important to make reports more accessible for various stakeholders and teams in the organization. Unfortunately, I often see teams afraid of opening up their dashboards, as it would again uncover the true engagement or acquisition numbers that may not look great to stakeholders. To avoid uncomfortable conversations or pesky questions, it’s often easier for teams to hide behind a veneer of complexity.

How to do it better:

- Step 1: Work with your engineering teams and analysts to simplify your product analytics event names: “Completed Onboarding” and “Added Dashboard Widget” are actions that everyone will understand.

- Step 2: If you have an analytics team, include them better in your product teams. The more context the analysts have of what your product team is working on, which experiments you’re testing and which questions need to be answered, the better they can help you to dig into the data to find the most relevant insights. It should be a collaboration rather than an outsourcing approach.

- Step 3: Make your analytics dashboards and reports accessible to the wider organization. Your dashboards should reflect your product’s key metrics (which you can define using the Holistic Metrics One Pager from the book). This is critical for scale (your team doesn’t want to get flooded with manual reporting requests every day) as well as to truly build a more data-driven culture within the wider organization.

“When teams are asked about the state of the business, they can either go look it up or make up hypothetical guesses. It’s critical to make the former the easiest, default way for leadership to respond to these requests by building custom, easy-to-use drill-down dashboards for things like cohorts, funnels, and user events.”

-Crystal Widjaja

Remember that the job we hired our data to do is to uncover the truth so we can take action and improve our product experiences. Making your metrics easy to understand and more accessible are key steps to include data insights into the day-to-day decision making in your organization. A strong product organization should be more motivated than ever to solve those problems once they know where the problems lie.

How to improve your metrics using the metrics checklist

I created a simple checklist that summarizes key characteristics of good quality, actionable metrics that will help you get more insights from your data. Use this checklist to assess and improve all your existing metrics:

- Is your metric uncovering the truth, and not a vanity metric?

- Is your metric comparative and does it give you a clear idea of its performance? (If not, try ratios!)

- Is your metric the best leading indicator to answer your question?

- Is your metric easy to understand so others can rally around it?

- Is your metric linked to the wider business goals and can you articulate the impact?

It takes real practice to truly get your key metrics right, and you will find the devil often lies in the details. It’s absolutely normal, and in fact encouraged to frequently revisit the metrics you have chosen, and to refine them several times to make them more useful.

Watch out for the pitfalls of sharing vanity metrics, focusing too much on lagging indicators where you have no time to course-correct, and make sure you simplify and democratize your metrics to truly level up the data maturity in your organization.

Corinna Stukan

CEO & Co-founder, Bizzy

Corinna Stukan is a product leader, writer and speaker at global product management conferences. She has led a wide range of B2B and B2C products across APAC, Europe, and the U.S. for companies such as Commonwealth Bank Australia, eBay, ASB Bank and Fletcher Building. Currently, she is the VP of Product at Roam Digital, where she grew the Product Management team and practice from scratch through growth and to recent acquisition. Read more of Corinna's writing on Substack or in The Insights Driven Product Manager.

More from Corinna