Why You Need to Keep Ego Out of Analytics

It’s not really about having an ego or not having an ego. It’s about accepting your ego and being aware of it.

According to The Social Network, Mark Zuckerberg invented Facebook after his ex-girlfriend broke up with him. It was his ego, the movie argues, that both drove him to succeed and doomed him to alienate those around him.

One of Facebook’s most important early team members paints a very different portrait of Zuckerberg. “I’ve never met anyone at such a young age who would truly listen,” Chamath Palihapitiya said of his management style, “In fact, he doesn’t need to talk a lot. He just sits there and listens.”

Zuckerberg takes in every possible perspective, Palihapitiya says, before he makes a call. In short, he’s pretty far from the bullheaded stereotype The Social Network portrays him as. But he also started a billion-dollar business from his dorm room, and that’s not something you accomplish if you’re a terribly modest human being.

Everyone has an ego. The key is learning to rein it in. “You can be confident,” as Palihapitiya points out, “You can be arrogant. It doesn’t really matter. But you can’t believe your own BS.”

We tend to think of data as objective, as neutral information, but that’s not really true. Nowhere is believing in your own BS more dangerous than your analytics dashboard. Your ego will cloud your judgment, you’ll make all the wrong decisions, and you will never understand why.

Go into your analytics with your ego, and you erase any chance you have of understanding what makes your business tick and what you have to do to grow it.

Your ego drives you to validate the wrong things.

The idea of the lean startup, once revolutionary, has now become standard startup operating procedure. You don’t even have to read Eric Ries to know the basics of what he calls validated learning:

- Define the metric you want to change

- Try something you think will change it

- Assess whether you moved towards your goal

- If you did, try again and again until you stop getting results. If you didn’t, try something else.

Your ego loves this idea. It means you can get almost automatic feedback on whether you’re doing the right things. All you have to do is look at a number and see if it’s going up or down: it’s objective, undeniable. Unfortunately, your ego is going to take this systematic process and use it to validate short-term variables when you should be optimizing for the things that bring you long-term value.

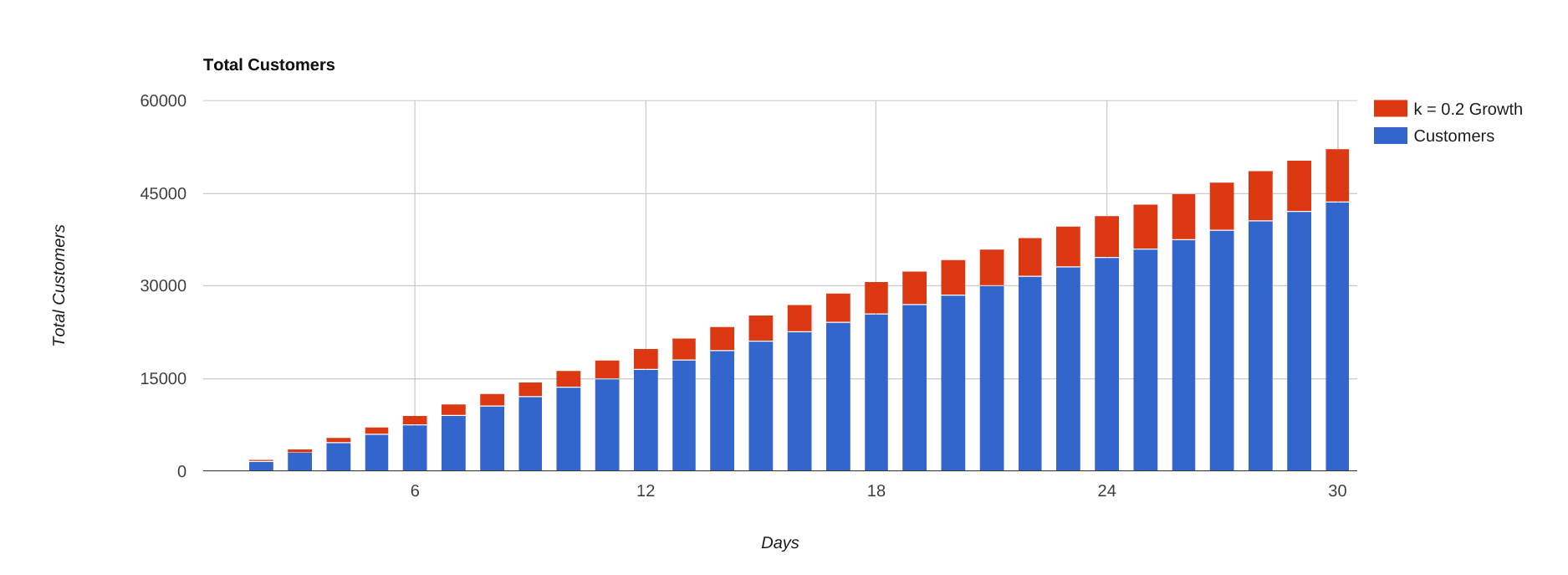

Take k-factor for instance. Everyone loves to talk about and optimize for k because it represents pure virality. If it’s above 1, that means that everyone who starts using your product spreads it to more than one of their friends: with that, you’re looking at huge, Dropbox-style, monumental growth. That’s an ego boost beyond imagination.

But there are two problems with obsessing over getting your k-factor above one:

- It’s pointless. As you can see from the graph above, non-viral referral, where your k-factor below one, is incredibly powerful in itself. The graph above depicts an app with solid user growth—about 1,500 new users a day—and the effect of a small referral boost. Even a measly k-factor of .2 gives each acquisition channel a hefty boost that after thirty days means having 55,776 users instead of 46,480—a difference of almost 10,000, or 20%.

- You are going to alienate your users and destroy your product’s core value if you pursue your k-factor relentlessly.

Alienation was one of Chamath Palihapitiya’s biggest concerns while they were building out Facebook, and not just because it was a waste of their time in the short-term to think too much about virality.

He saw optimizing for k as the easiest way for a business to start (even inadvertently) spamming their users, and he knew that would destroy Facebook over the long-term: “You won’t see [the effects] today, but you’ll see in three years from now, and it accelerates when you compound that with a competitor who actually builds a better product that doesn’t alienate people.”

“Don’t give me these low-level abstractions that allow you to validate, get short term results in ROI that don’t mean anything,” he says, though he concedes that this is difficult. The only way to overcome the temptation, he says, is to focus on the kinds of changes that will actually help you deliver product value in the long-term.

Your ego sees only what it wants to see.

Optimizing for the long-term future of your app means using your analytics to find patterns of real usage. You need to find the actions that users are really fond of, like Burbn did when they noticed users were doing a lot of photo sharing—that’s how it became Instagram.

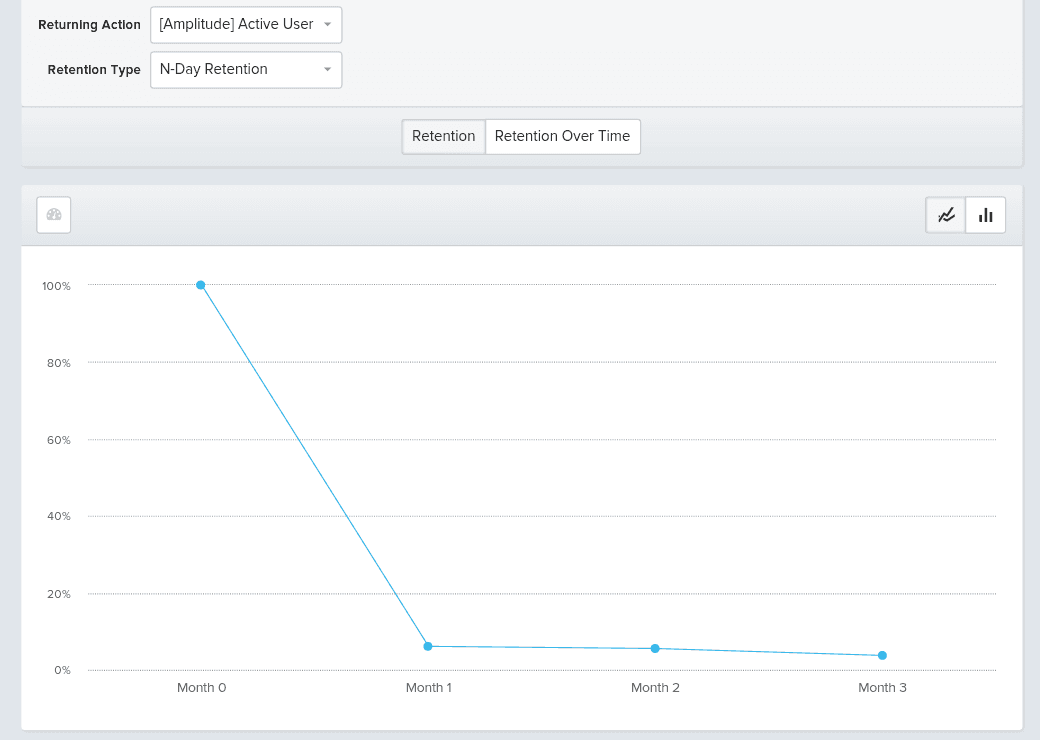

But when you let your ego do the thinking, you’re going to have a much harder time finding the right factors. Let’s say you open up your dashboard and look at your daily active user numbers for first couple of months after launch:

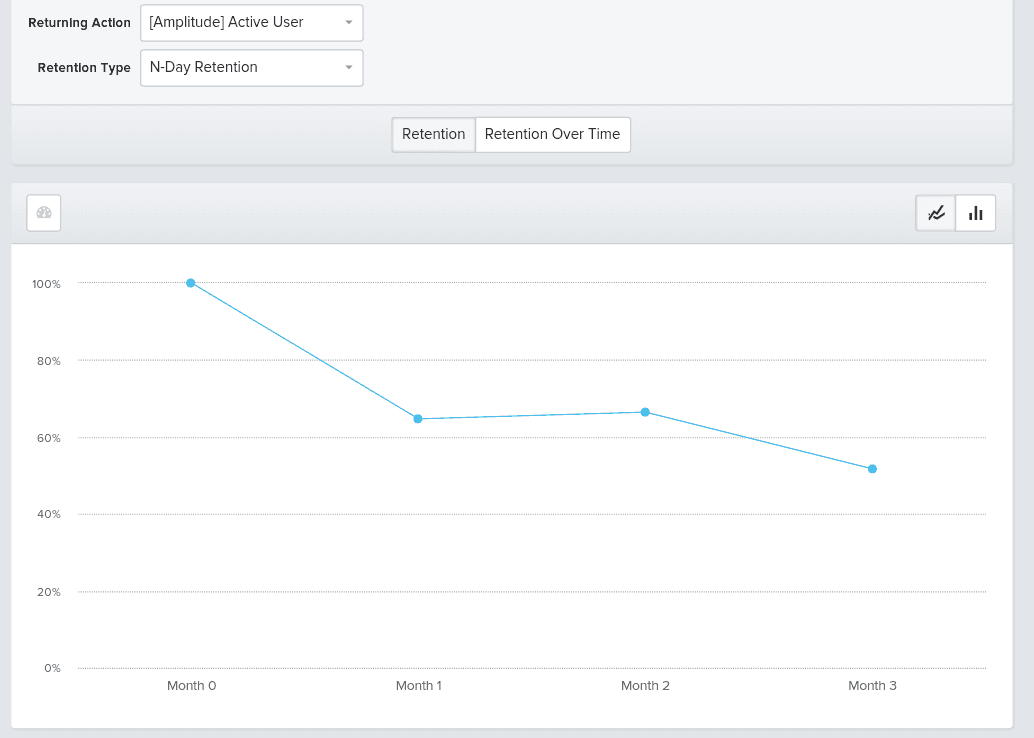

Pretty lousy—after about a month, less than 10% of your initial users are still active. But you recently decided to redesign your app. A lot of people on your team were skeptical that it was the best use of time for your engineering and design teams, but you were adamant. You pull up the last three months because you want to see that your design change influenced your active user count in a positive way:

That’s a serious uptick in usage! There’s a 60% increase in users still active after one to two months, and about 50% for the third month. You swell up with pride, and you rush to tell your colleagues about this amazing success you’re responsible for.

Why are you wrong to do that? Because of one of the basic principles of any kind of analysis: correlation is not causation. It’s really easy to find two variables moving in the same direction. That doesn’t mean they’re related.

You set out to prove a specific thesis (that your design change was responsible for an increase in usage), you looked at one set of metrics, and as soon as you found proof for your claim, you stopped.

There is a wide variety of variables at play. You could set out to prove just about anything and find something to support it. That’s why the best way to use your analytics is backwards.

What that means is coming up with a theory, then setting out to disprove it. You’ll spend a lot more time doing this, but it’s more methodical. It narrows down the possibilities. If you look through all your analytics and can’t figure out any other cause for the increase in usage, then you have much stronger ground to stand on.

Your ego won’t like it, but it’s the only way to come to a scientific conclusion.

Your ego wants the easy way out.

When you read about billion dollar companies like Facebook, it never seems like growth was too difficult to come by. There might have been some initial struggles, sure, but as soon as they figured out the “7 friends in 10 days” formula? Smooth sailing.

Your ego loves that idea the same way it loves Zynga’s idea of building games around metrics, or Dropbox’s idea of incentivizing referral with additional storage. Why? Because they’re magic bullets, and smart entrepreneurs find the magic bullets that lead to hockey stick growth.

Or they seem like it. Of course, in real life, Facebook didn’t even have an analytics platform. They analyzed all their metrics by hand, which meant endless hours spent coding and making mistakes. All the while, they were dealing with angry users, the FCC, and hostile foreign governments.

Nothing about it was easy. “7 friends in 10 days” wasn’t a magic bullet, it was the culmination of years of work understanding user behavior analytics. But your ego has a hard time believing that. Your ego thinks that working hard means something is wrong. Your ego thinks that every business worth a damn “hacks” its way to growth. Your ego is convinced that all you need to build a billion dollar business is your own magic bullet.

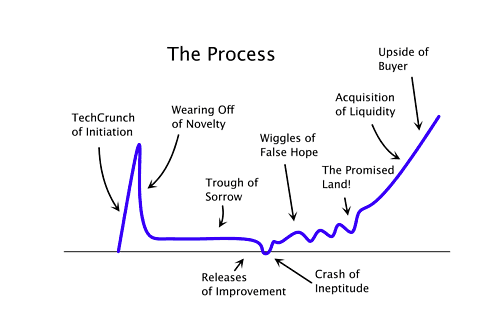

The truth is that even hockey-stick companies like Facebook go through the same travails as any startup:

A “hack”, or a magic bullet, is not going to get you through the severe ups and downs that come along with starting a business. There’s always going to be disappointment, and sorrow, and crashes, and false hope.

The only way to get through it is to work hard and believe in your vision. This doesn’t mean you can’t read about other companies and learn from what they did. You just have to maintain some perspective. Understand that they faced different problems, and existed at a different time. Look for what you can take to your own work, but don’t think that you can apply their methods piecemeal.

You can’t believe your own BS.

It all comes down to being able to hold two fundamentally opposed ideas in your head.

You have to keep your distance. “If you can’t be extremely clinical and extremely unemotionally detached from the thing that you’re building,” Chamath Palihapitiya says, “you will make massive mistakes and things won’t grow because you don’t understand what’s happened.”

At the same time, you poured your blood, sweat and tears into this. Cold, detached analysis doesn’t start businesses: passion does.

In the end, it’s not really about having an ego or not having an ego. It’s about accepting your ego and being aware of it. It’s about taking part in a balancing act that every entrepreneur goes through, and it’s about building something incredible in the process.

Comments

Benjamin Brandall: Thrilled to have stumbled on it!

Archana Madhavan

Senior Learning Experience Designer, Amplitude

Archana is a Senior Learning Experience Designer on the Customer Education team at Amplitude. She develops educational content and courses to help Amplitude users better analyze their customer data to build better products.

More from Archana