Here’s What Slack Needs to Do to Become an Operating System

A world where Slack is not a chat application off to the side of your real work, but the center of all your work.

The future of Slack, messaging app and reportedly the fastest growing business app of all time, has long been the subject of intense speculation. After Microsoft nixed plans to acquire the now-$3.8 billion company, analysts weighed in to predict that Slack would reinvent everything from online documents to Facebook.

At a Friday press conference, however, Slack CEO Stewart Butterfield put the rumors to rest, offering up the clearest statement we’ve heard from Slack about what the high-flying company wants to be next.

The future of Slack, he said, is to become the “browser and the command line for the enterprise”—in other words, a whole new operating system just for businesses.

Meet The New Command Line

While the word-of-mouth around Slack shot it straight to ubiquity in the offices of tech startups and media organizations, enterprise adoption has been slower. And Slack knows why—communication overhead.

Today, the Slack team (now 400+ employees) is using 80 different pieces of software internally.

When you are _also _communicating in Trello, Google Docs, Quip, Zendesk, et al, Slack can easily become just another source of noise. And if you’re on a Slack team with Twitter/Giphy integrations, then you know it takes team-wide discipline to keep things at a reasonable volume. A whole subgenre of “I’m leaving Slack” thinkpieces has been born from the problems organizations have using Slack at scale.

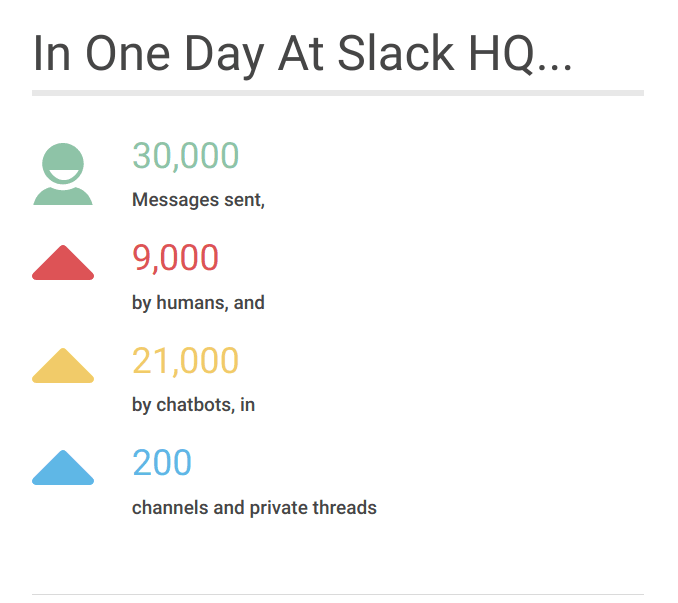

Butterfield and the Slack team have a plan, however—and that plan involves bots. How Slack uses Slack. The vast majority of messages sent are not sent by humans, indicating how seriously Slack themselves take automation and app integrations.(Source)

With bots that can pull data from any third-party app, help you find the latest version of a file, and even automate repetitive work tasks, Butterfield wants Slack to become the hub for all the critical activities of your business.

It is a world where Slack is not a chat application off to the side of your real work, but the center of all your work.

To get there, Slack has an classic analytical challenge in front of them. They have to find their “power users” and learn from them. When you’re analyzing your user base for insights into retention-building, you don’t just look at a cross-section of all users. You pick a view that matches your goals. For Slack, that view needs to be specifically tailored for growth and retention in the enterprise—they need to find the users already using them as an operating system.

Crossing The Chasm

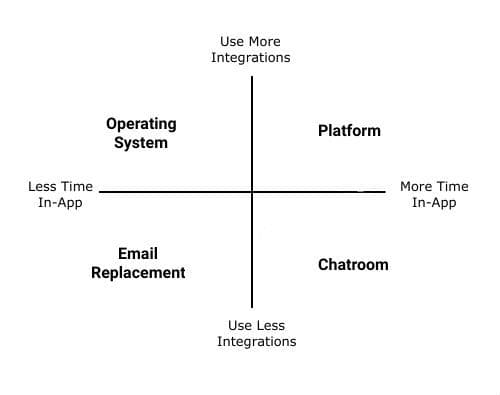

The management consultant Geoffrey Moore’s 1991 book _Crossing the Chasm _is considered by many to be like a Bible of entrepreneurship. In it, he talks about how as companies grow, they have to focus on serving the needs of one customer base at a time. Slack, in making a more enterprise-friendly product, has to think about the different kinds of users on its platform and zero in on what makes them different. To figure out the users they want to target, it would make sense to separate out their user base based on the amount of integrations in-use and the amount of time spent in-app by each group: These behavioral personas differentiate users on the basis of how they use Slack, whether that’s as a:

- **Chatroom: **Slack as an IRC replacement, a method for keeping in touch with diverse groups of colleagues, family, and friends. Users spend a lot of time in Slack and use few app integrations.

- **Email Replacement: **Slack as little more than an email replacement, as a method of lessening the communications overhead of email and keeping all conversations in one real-time repository. Users spend as little time in Slack as possible and use few integrations.

- Platform: Slack as a platform for applications not routed to third parties. Think Giphy/Twitter/CatFacts—apps that can provide a break to your day or supplement Slack’s features without integrating with your business tools.** **Users spend a lot of time in Slack and use many integrations.

- **Operating System: **Slack as the command line and browser of the enterprise. Operating System users are in Slack as little as possible, but use a wide range of integrations while they are—they’re checking Trello cards, finding Google Docs, locating files in Drive, looking up companies in GrowthBot, etc. Users spend as little time in Slack as possible but use many integrations.

Looking at users **already using a lot of integrations **while spending a minimal amount of time in Slack is critical. While a smaller company may be able to shrug off the communications overhead created by the “always-on” nature of Slack, a larger enterprise company is going to have a lot more friction to deal with if people see Slack as merely _another _app they need to check. To ease these anxieties and prove its value, the enterprise use case for Slack needs to be aligned around productivity. Until Slack can be a clearinghouse for all of a business’s critical activities, it’ll just be a tool. It needs to become _the tool—a truly vital and sticky component of the enterprise.

Finding OS Power Users

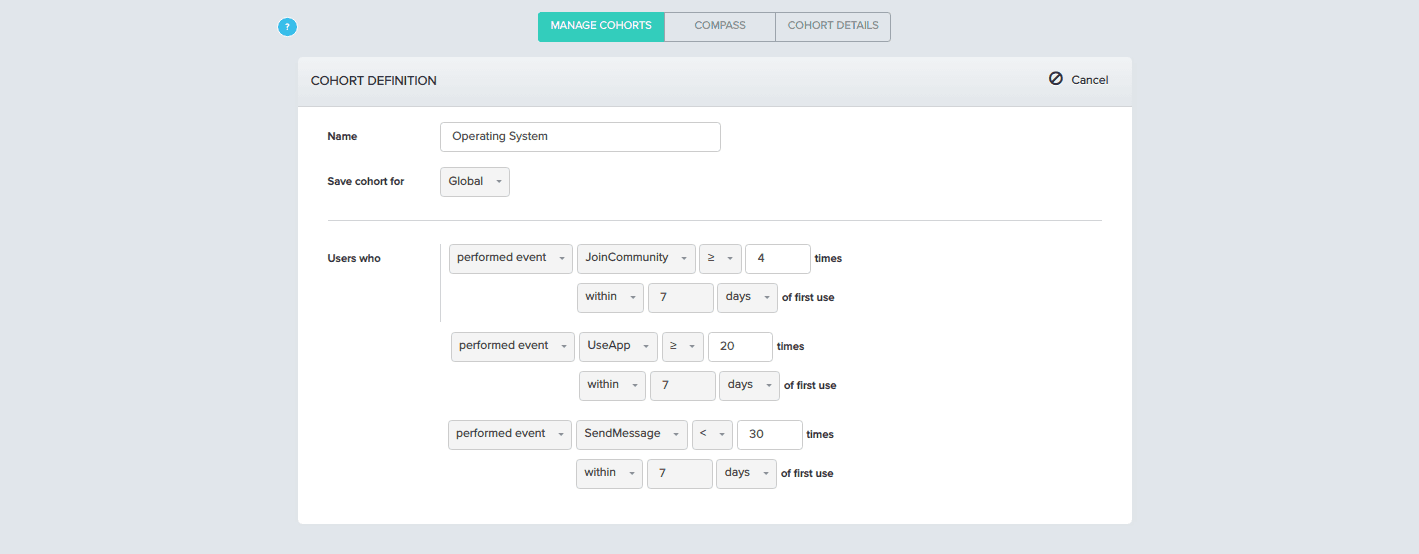

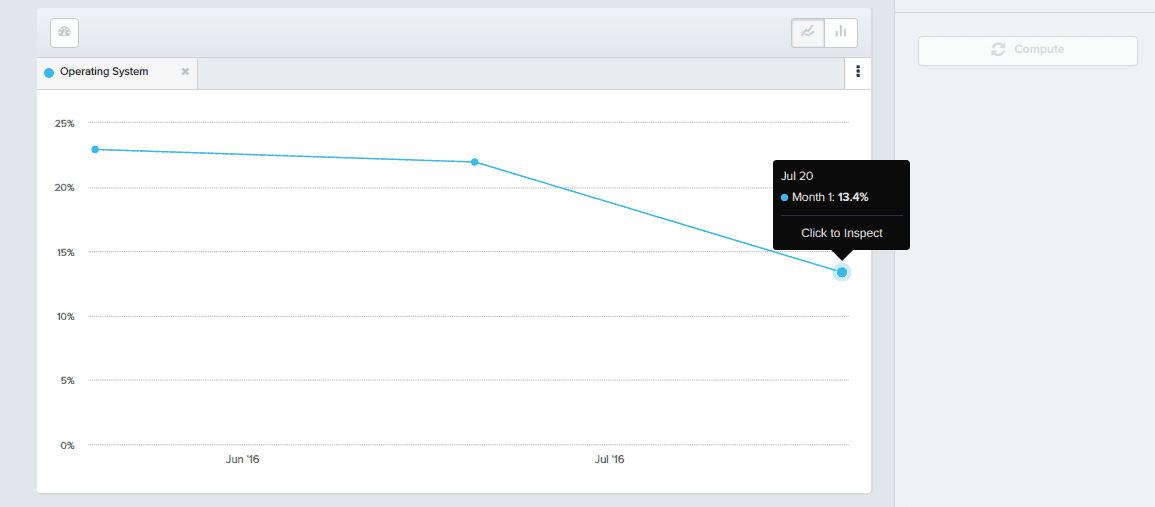

The first step of our analysis has to be looking at the **Operating System **users that we can verify are getting value out of Slack. To do this, we’d first create a cohort of users based on the kinds of behaviors that we expect out of our Operating System power-users: We presume that Operating System users will be in Slack just about as often, on a day by day basis, as normal users. But they will use many more apps and send fewer messages, so we specify that in our cohort. Then we analyze the retention of that cohort over the last three months: It’s that group of users that stuck around for three months that we want to zero in on, so we Click To Inspect and then create a new cohort based just off of them. Now we have a cohort of users that **are regular Slack users (**signed in >3 times in a week), use 3rd party apps a lot (>20 times in a week) and **send fewer messages **(<30 in a week). We can now delve deeper into this cohort and look at what features are really keeping them coming back.

Feature-By-Feature Retention Analysis

When you have a mature app, near-platform status, and too many moving parts for behavior-by-behavior cohort analysis, a tool like Compass can be incredibly useful.

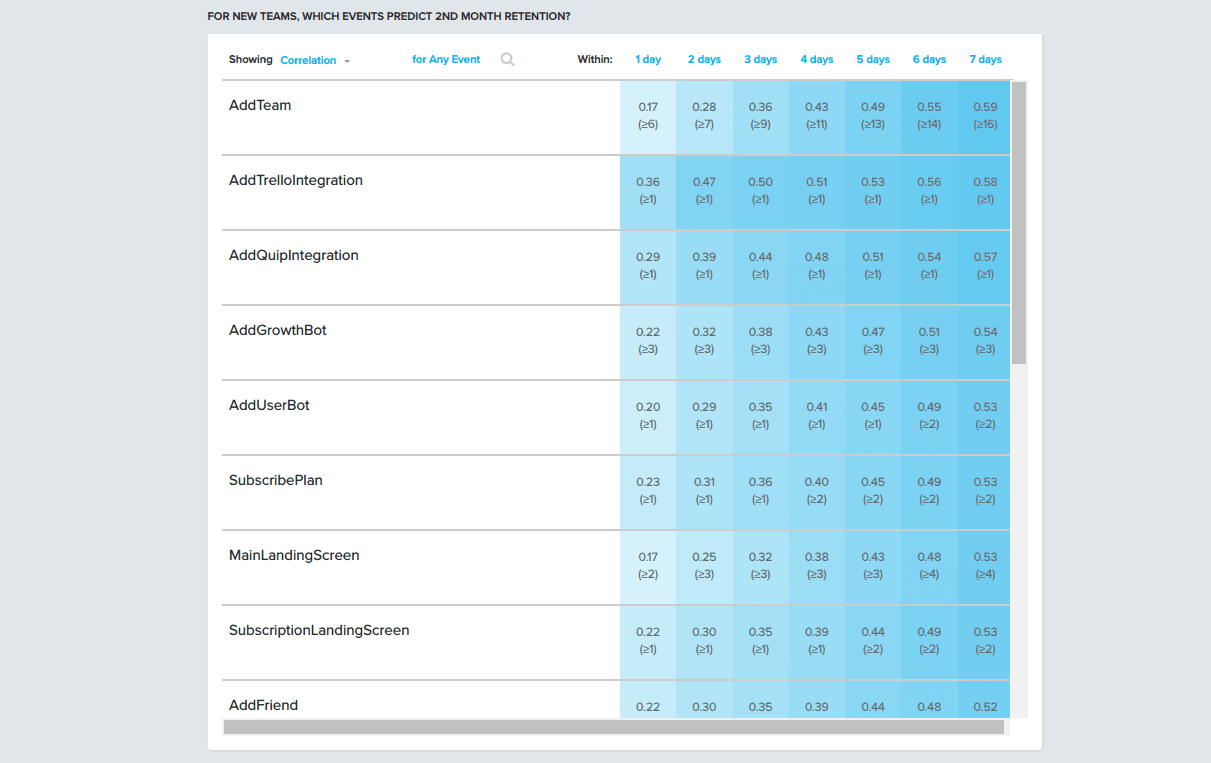

Let’s say we’re looking at the actions that our Operating System cohort users are taking in their first seven days as Slack users. You want to understand which events are most predictive of second-month retention—what kinds of integrations, for instance, the users that stick around are installing.

These will likely be discipline-specific. It make sense to even create new cohorts for, say, developers, marketers and salespeople—since the integrations they’re going to use are very different.

For each cohort that you chose, you could open up Compass, pick the events you’re interested in, your timeframe, and get a graph of behaviors correlated with retention analytics for that cohort: By looking at the activities most correlated with retention in the Operating System cohort, Slack can start to understand what kinds of behaviors and integrations are the most predictive of retention for those users.

What This Means For Slack

With this kind of analysis, Slack could come to learn, by inference, how enterprise companies can grasp the value of Slack faster. They can find new ways of proving that Slack isn’t just a fun chat app for smaller tech startups—that it can truly break through its current ceiling and become something even more unprecedented than a business app that’s fun to use.

They could prove its viability as the command line of the 21st-century and then start working to build that reality.

That potential future—our work lives revolving around a single hub, designed with user pleasure in mind, providing quick access to every facet of the business—is a future that Slack can make possible.

To make that future real, however, Slack needs to find its users who are _already _living in that future—then figure out how to work backwards to build the product the enterprise truly needs.

Archana Madhavan

Senior Learning Experience Designer, Amplitude

Archana is a Senior Learning Experience Designer on the Customer Education team at Amplitude. She develops educational content and courses to help Amplitude users better analyze their customer data to build better products.

More from Archana