The Anti-Influencer Marketing Strategy to Grow Your Community

This post is part of our Product Innovator Series that explores what it takes for businesses to survive and thrive in the product-led era.

I hate the term “influencer.”

In tech, you can often find “influencers” talking about various new developments on TechCrunch and Fortune, while other people (who are actually the best at what they do) are in the trenches, working.

Entrepreneurs who are building new products will sometimes chase after those influencers and the audiences they come with, forgetting the rule of 1,000 true fans (as stated by Kevin Kelly):

To be a successful creator you don’t need millions. You don’t need millions of dollars or millions of customers, millions of clients or millions of fans. To make a living as a craftsperson, photographer, musician, designer, author, animator, app maker, entrepreneur, or inventor you need only thousands of true fans.

Your community’s quality isn’t a function of its size—its a function of the passion and reputation of the people within it. If you want to build a product with a great community, or if building a great community is part of your product, then you need to optimize for that passion and engagement. You can’t optimize for sheer size.

When I started Quibb, which just shut down last month, I wanted a place where tech and product people could find meaningful articles, read them, and start great conversations with other people in their field. Here are some of the simple tactics I used to make sure our community could live up to that vision.

Monitor onboarding to the community by asking for qualifications

The “just sign up” ethos is so ingrained in how we think about consumer products that it almost feels like blasphemy to not follow it. But plenty of products practice some kind of limited or monitored onboarding, at least early on.

When you sign up for the beta of that hot new product that just launched on Product Hunt, you’re asked who you are and what you’re going to do with the product—often, your answer to that question is what will dictate whether or not you’re invited.

Asking for a certain degree of qualifications from your earliest users is one of the best ways to make sure you keep the early community within your product the way you want it. It was certainly key to Quibb’s growth as a community.

When you went to go sign up for a Quibb account, you weren’t approved right away—you had to wait as I (yes, I) lightly cyber-stalked you and determined whether you were involved in the tech world enough to join the site.

Why would you want to bother with this process (and presumably, the possibility of rejection) for some random site?

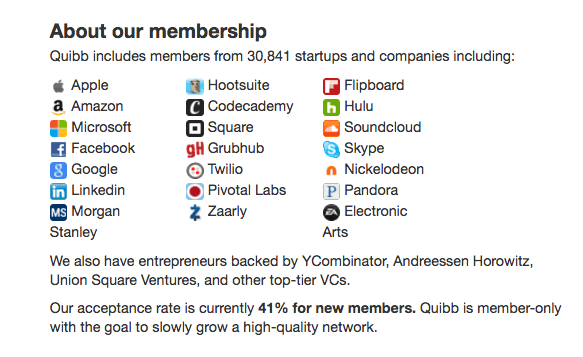

When Quibb started, I drove around San Francisco asking people to join it in-person, so it’s not like they wanted to from the start. Eventually, however, the big names that were signing up for the site started to act as little indicators of social proof in and of themselves.

Working at Facebook or Apple or Amazon doesn’t make you a better engineer or product manager, nor does being backed by Y Combinator mean you’ll be successful, but in tech, it does matter who you are and where you work and the kinds of experiences you’ve had. This proved very useful for encouraging applications to Quibb. When you see that people backed by Union Square Ventures, who work at Square and Google, opted into this experience—it raises the level of credibility pretty significantly.

It also raises the level of the discourse on the platform, which was the real goal all along. It works the same way with any kind of product. If you keep somewhat of a close guard on your early product, you can learn about how customers use it and what needs to change in a more controlled, tempered environment. You can see how certain types of people use your product differently from everyone else. And that can help you see how to make the product better, in the end, for everyone that uses it.

Show that other people you want to know are part of the community

A great social product experience isn’t just about the features of the product—it’s about all of the other people around. That’s why you need to build that social capital and that value into the product if you want it to be the best it can be.

Take HQ Trivia. You don’t really care about the comments at the bottom of the screen when you’re playing. You can, as the game suggests, even swipe them away so they don’t bother you. And yet they play a powerful role in keeping you engaged in the game as a social experience. The comments tell you both that there are truly thousands of other people playing, and that the game is truly the live, ephemeral event it feels like it is:

Quibb’s invite-only application structure was designed to limit the userbase to only those with a legitimate stake in the tech community and some kind of credibility (startup employment, funding, etc.). The way content was presented on Quibb was designed to drive home that point. Each individual article uploaded to the site told you not just what you should care about but why you should care about it:

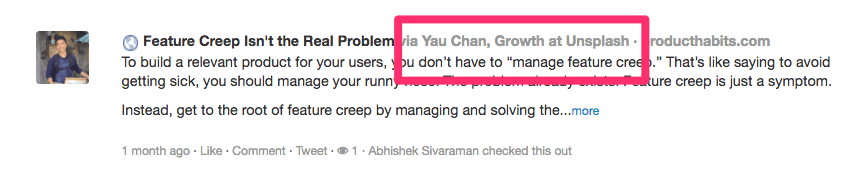

Normally, on sites like Hacker News or Reddit, posts are attributed to handles, or screen names. On Quibb, I decided to attribute every post to both the person who posted it and their role. You’re not just seeing Yau Chan post this article about feature creep—you’re seeing Yau Chan, Growth at Unsplash, post this article about feature creep.

If it was just ychan2421, or Yau Chan, you might not know what to do with this article. It might just be another piece of noise, another article shared that you’re not going to read. That extra piece of context, however, tells you a lot—it tells you that someone with a very specific set of experiences and knowledge found this article useful. Suddenly, the article becomes something much more than another piece of noise in the product’s feed.

Just because it has a line doesn’t mean it’s cool

The classic influencer strategy is all about using big names and big credentials to draw as many users to your product as possible.

It’s like putting a line outside a nightclub to try and convince people that there’s something valuable going on inside that they can’t get anywhere else.

That doesn’t, however, mean that you should always let the floodgates open when it comes to launching a new product. Careful curation of your early users can be a powerful way to get better insights into your product’s usage faster. It can help you build a better, more cohesive community. And combined with a UX that reinforces the value of that community, you can build a social product that—while it may not grow at hyperspeed—will have a much stronger foundation for growth.

Editor’s note: This post is part of our Product Innovator Series that explores what it takes for businesses to survive and thrive in the product-led era.

Featured photo by Paul Dufour on Unsplash

Sandi MacPherson

Product Manager, TrustLab

Sandi MacPherson is a product manager who has worked at Nextdoor and Quibb.

More from Sandi