Creating Flow and Value in Product Development

In this 7-minute video, I explain why limiting work in progress can increase flow and value in product development.

Let’s consider the time it takes to go from agreeing to do something to a customer receiving value. It may come as a surprise, but most of that time is not spent working. It’s spent waiting—waiting in backlogs, waiting for other people, waiting for feedback, waiting to be rolled out and adopted. In this 7-minute video, I explain why limiting work in progress, the scope of work, and handoffs between teams can increase flow and value in product development.

Watch the video

Read as an article

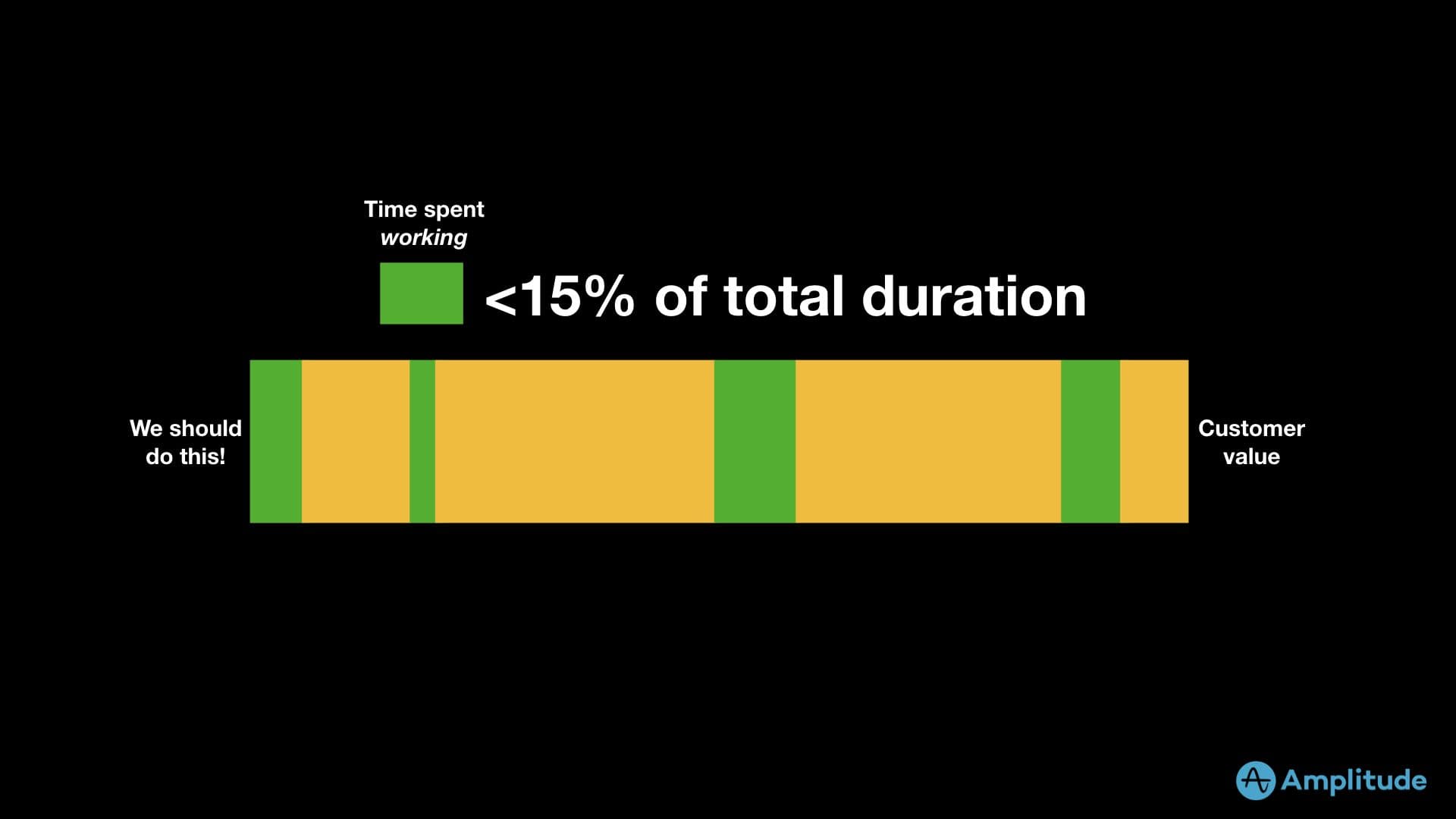

If the time from idea to customer value is 100 days, for example, in many companies you’ll find people working for 15 days or less, sometimes a lot less. So let that sink in. 15% of the total duration is spent actually working, yet this time, the time we observe teams working is what we seem to obsess over as product developers.

“Crap delivered quickly, even if we deliver it sustainably, is still crap; unless we learn something and act on that learning.”

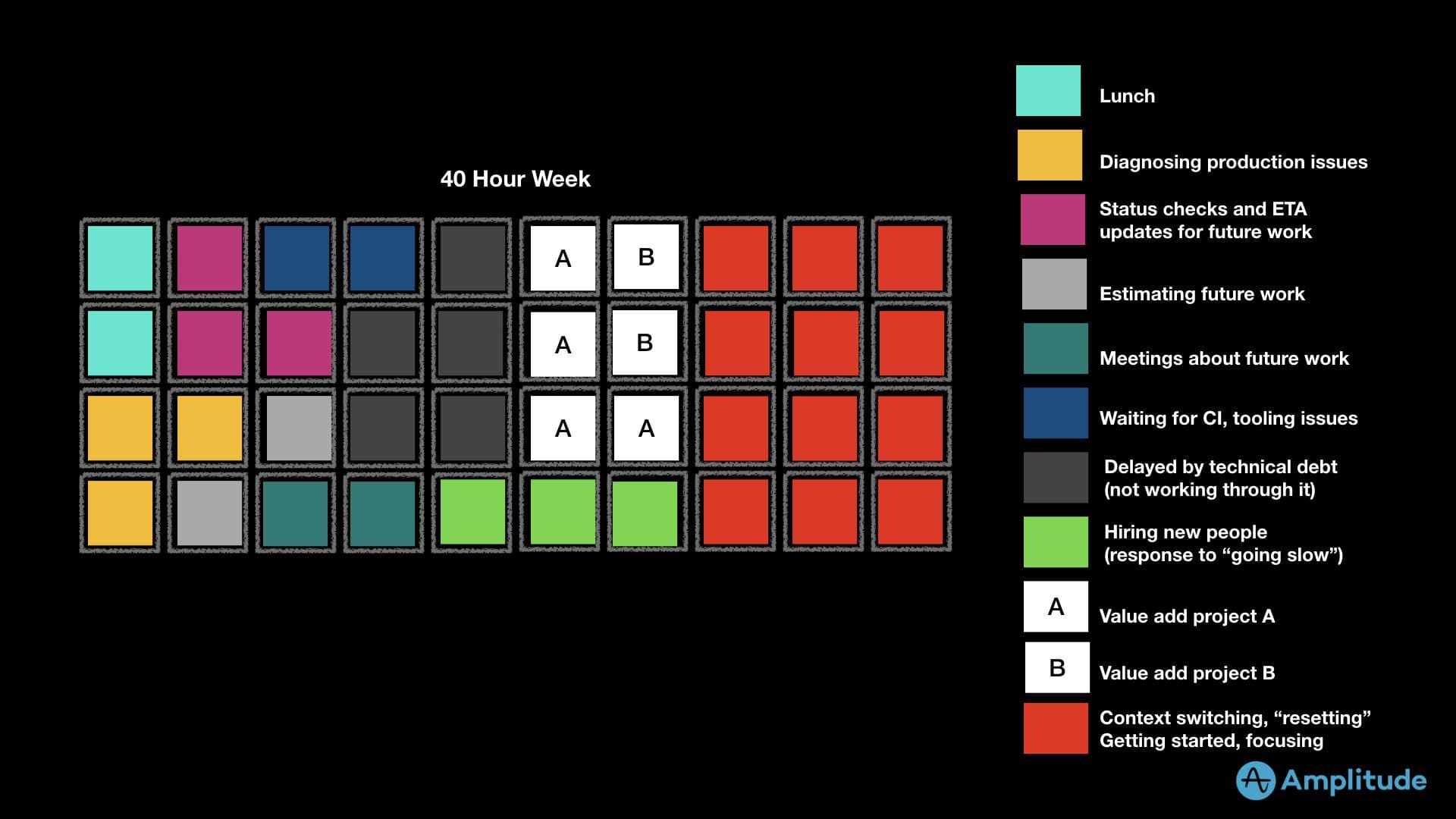

That 15% number is interesting, but it might feel a bit abstract. Let’s take another angle. Consider a 40-hour work week. Let’s see where the time goes for an example product developer.

So you’ve got lunch. They’re diagnosing production issues, doing status checks. You’re estimating future work. You’re doing meetings about future work. You’re waiting for CI and tooling issues, being delayed by technical debt. They’re hiring new people because they’re told they’re going too slow. They’re working on two actual efforts, and the rest of the time is spent multitasking, context switching, resetting, and getting focused.

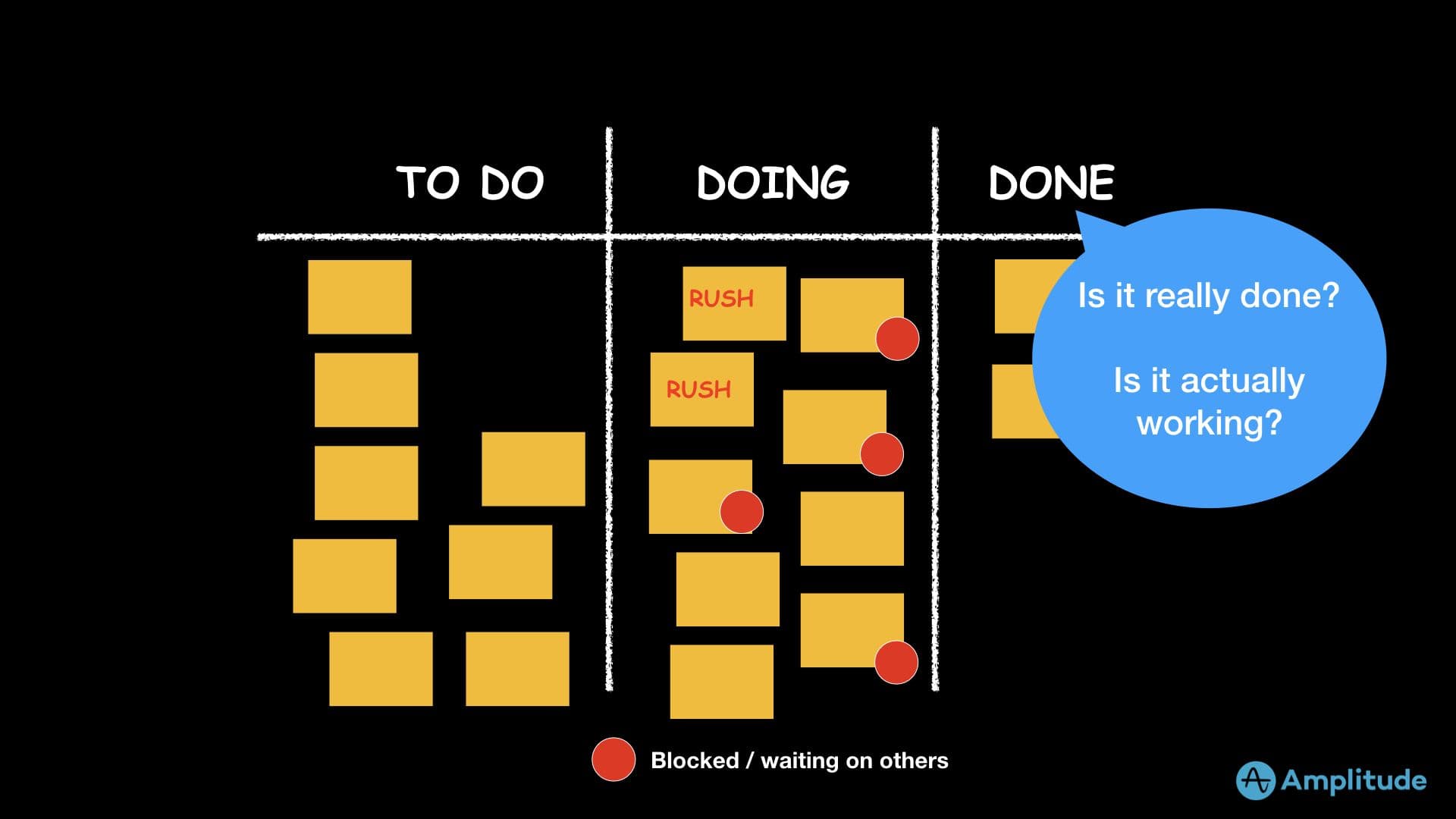

So why does this happen? First, look at all that work in progress. I’m guessing some of that work is actually blocked. When we finish work, we don’t focus on other balls we’re juggling, we pull in two rush jobs. And are the things in done actually done? Are they working and producing value?

“A lot of this is being human. We’re pragmatic, we’re optimistic. We want to please and let people know we care about their requests.”

A lot of this is being human. We’re pragmatic, we’re optimistic. We want to please and let people know we care about their requests. We want to respect other people, and we want to avoid conflict whenever possible.

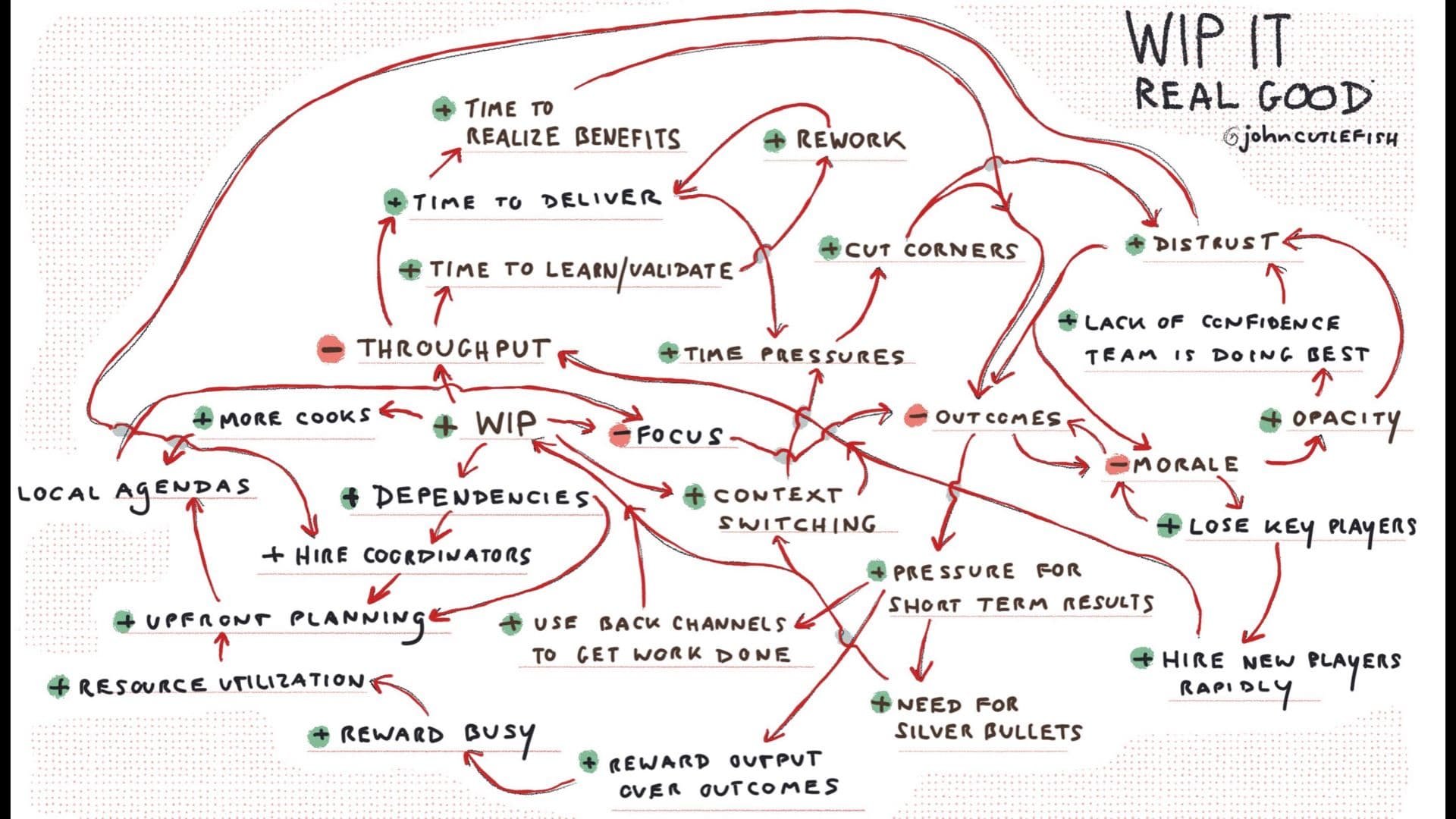

Add lots of people to the mix, and things get complex and surreal very quickly. Imagine work in progress goes up, throughput will go down, which means time to delivery will go up, which increases time pressures. We cut more corners. The value we deliver drops, which saps morale, which adds pressure for short-term results. Oh, hey, we need a silver bullet. And now people use back channels to get work done. So WIP goes up, so do dependencies, so we have to hire coordinators, which along with dependencies require upfront planning, encourages local agendas, which then sows distrust. And that’s just one path through the mess.

We think more upfront planning, stricter definitions of done, better estimates, more resources, and clearer team commitments will help.

But actually the less intuitive stuff helps, like less work in progress, smaller batches, fewer hand-offs, cross-functional teams, more flexibility in terms of scope, fixing underlying issues impacting flow, and cross-training people. But even with that flow we have an issue. Crap delivered quickly, even if we deliver it sustainably, is still crap; unless we learn something and act on that learning.

Because there are really two types of velocity. Output velocity, how quickly we deliver, and value creation velocity, how quickly we create value.

One is the feature factory. And one is better thought of as a value creation system. So say someone offers to pay you $200,000 if you build something that does A, B, or C. So another person shows up and says something like, “Hey, we’re 60% confident we should focus here. We have a couple ideas we’d like to try. If we’re successful, it should impact mid and long-term revenue.”

The person on the left is talking projects. The person on the right is likely talking product.

The person on the left considers his costs, salaries mostly, and profit. The person on the right is thinking about creating long-term value, a stream of revenue.

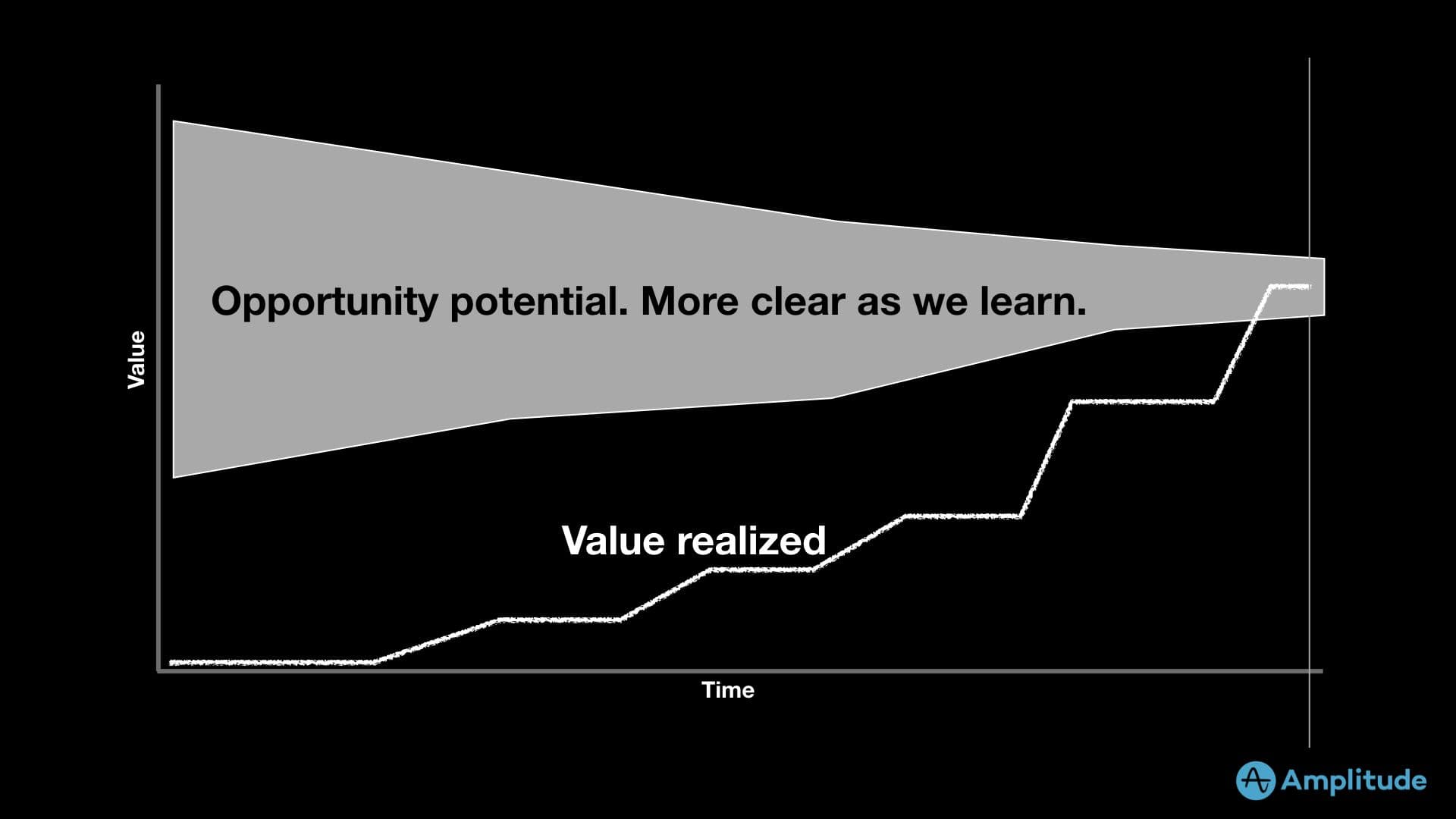

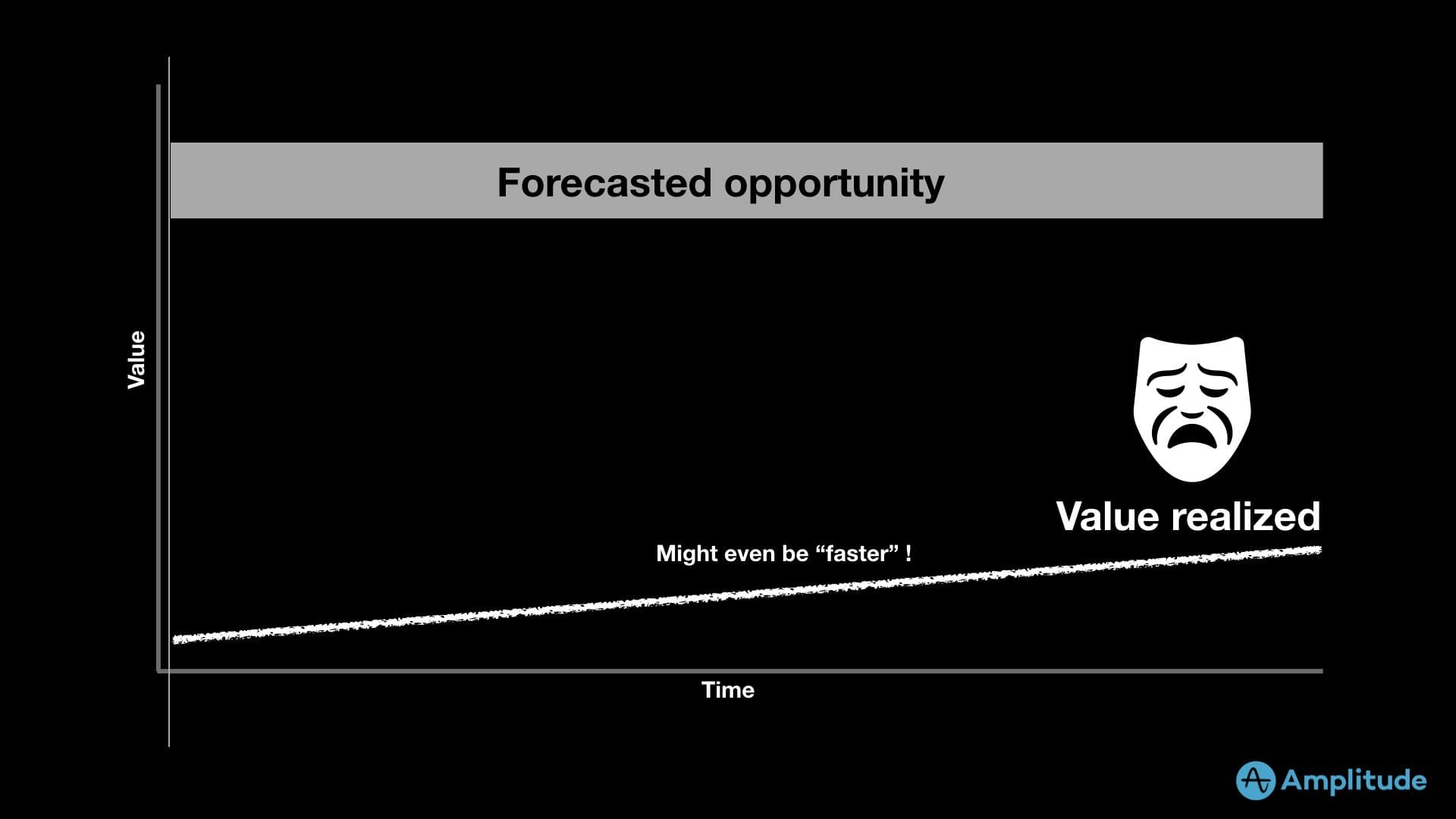

So with product we’re placing bets. The nice thing about working iteratively is that we can actually bet after the work has started and we can adjust our bets based on feedback.

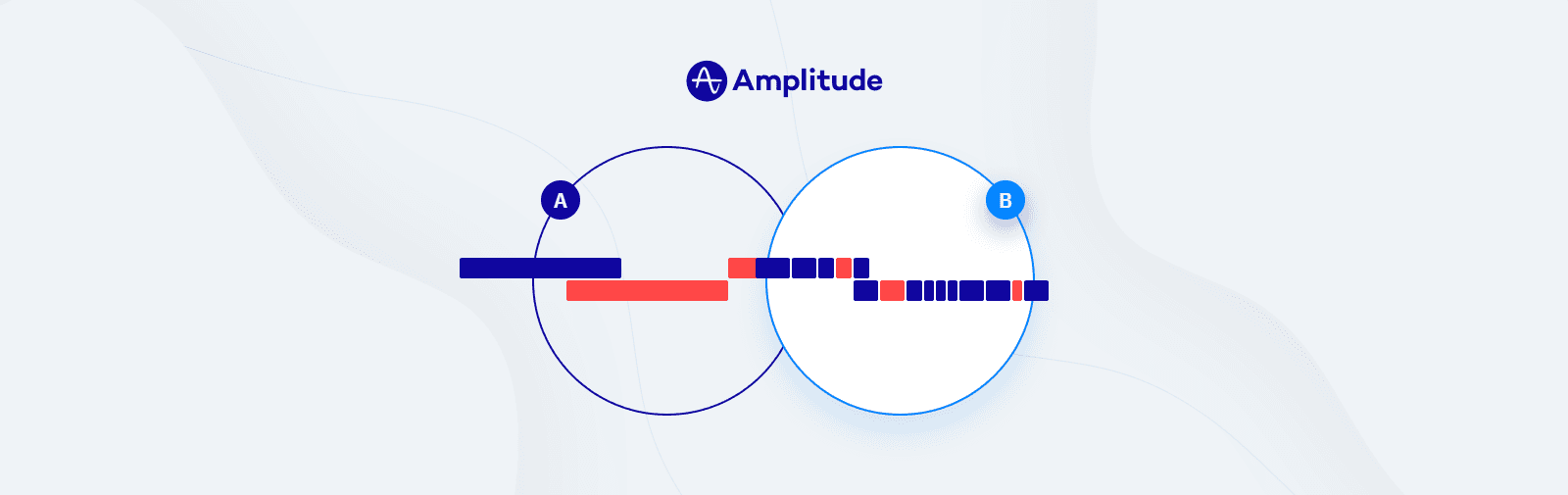

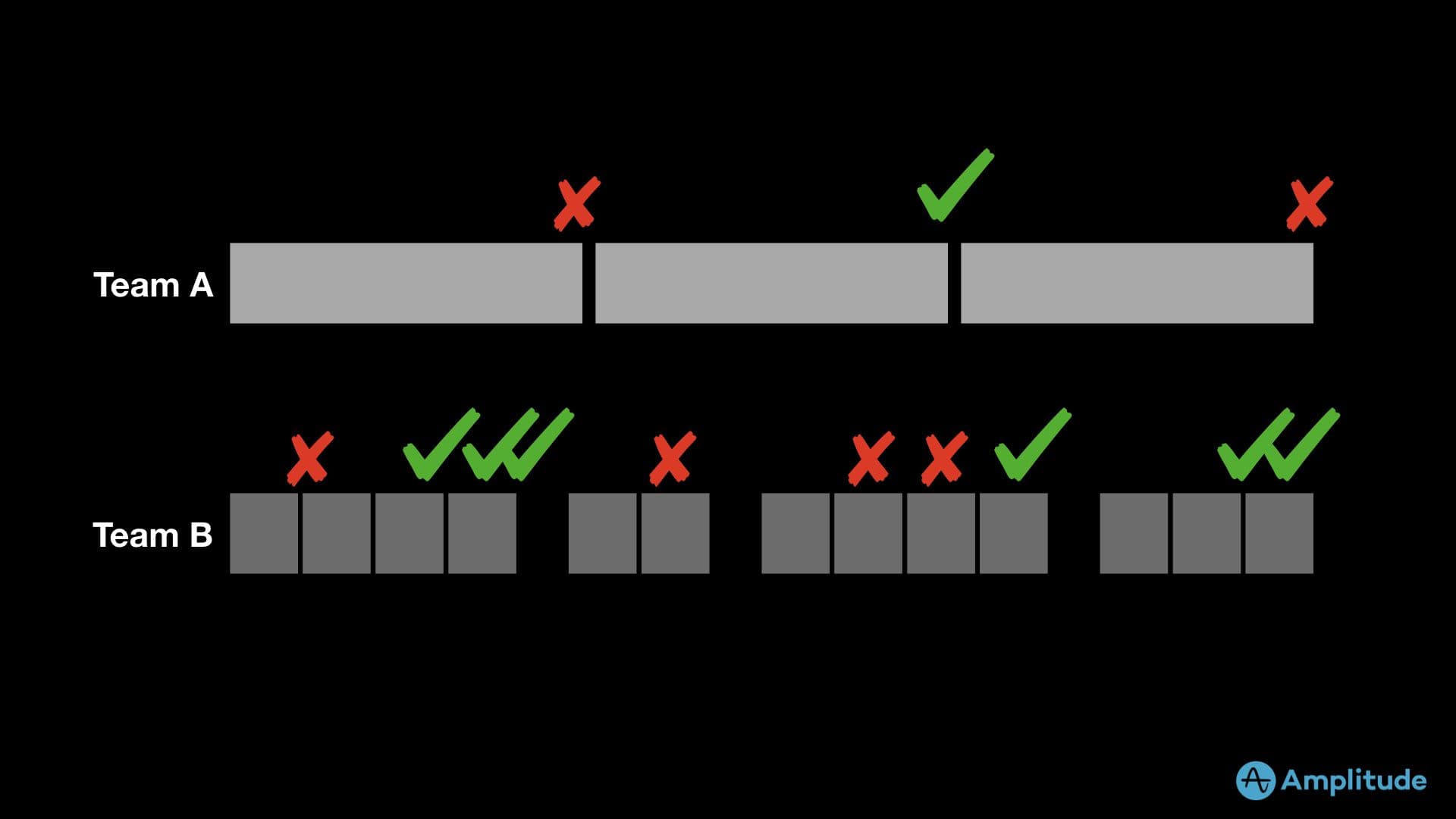

Batch size in our approach to feedback matters. Here Team A places three bets. Now Team A works in smaller batches. So what does this mean? No one is perfect. Team A notches one winner. Now Team B misses two, but they learn, they’re able to discover what works. They have more green checks.

Speed matters, but so does flow and cadence. If you’re sprinting, but not learning, the speed is for naught. So both of these teams are moving at the same speed.

The rightmost team is going through the sense and respond cycle more rapidly. Their cadence is shorter. My money would be on the team with the higher cadence, even if they were actually a bit slower.

Of course, we should target worthwhile opportunities. So if we work iteratively in small batches, we’re able to clarify our understanding of the opportunity, and realize more and more value as we learn. This other team forecasted a big opportunity, but didn’t learn.

They took one shot at their understanding of the problem. They put all of their eggs in one basket, and it didn’t work out.

To work this way, teams must be allowed to converge later, which is very hard when everyone wants to know when and what. In the top example, the team does a more traditional analysis phase. They converge on a solution. The team develops the solution, and then they ship it. In the bottom example, the team converges on an opportunity to tackle, and then they take a more continuous approach to design and development.

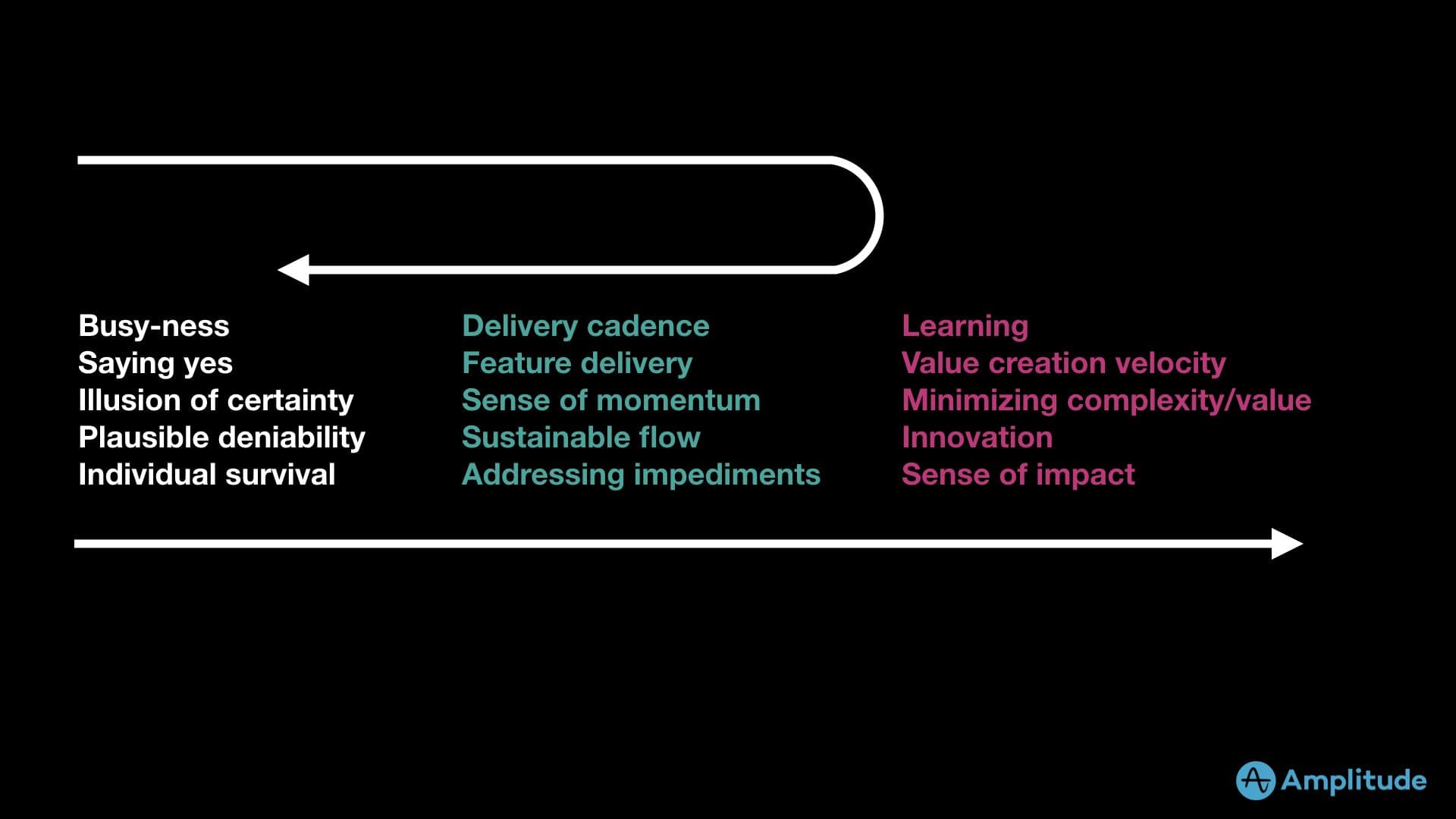

To summarize, there’s three stages in creating flow and value in product development.

The first is systems optimized for busy-ness—saying yes, the illusion of certainty, and individual survival. There’s no flow. Everyone’s busy, but with little to show for it.

The second is the well-oiled feature factory. We have a sense of momentum. The team delivers usable features. There’s sustainable flow and instead of ignoring impediments, the team addresses those things head on.

The third is the value creation system. The team is optimized for learning and innovation, for value creation velocity. They try to avoid feature puke whenever possible. So danger of getting stuck on stage two is that with all those features it is easy to fall back to stage one, which is why I advocate for tackling stage three, becoming value focused.

On a high level, there are three steps to get here…

- Come up with your best guess of a model for how value is created and how a created value is monetized.

- Focus on where you want to intervene. This is your opportunity. It’s a place where you see the most leverage.

- Finally, come up with some things you want to try. Try them. Then amplify what works, and dampen what doesn’t.

Tools and partners help. At Amplitude where I work, we believe in empowering frontline product teams with accessible insights geared towards helping them do their most impactful work. It’s meant for teams working in the trenches, moving quickly, with decision authority, and trying learn and create value.

Download the deck on slideshare

Creating Value and Flow in Product Development from Amplitude

John Cutler

Former Product Evangelist, Amplitude

John Cutler is a former product evangelist and coach at Amplitude.

More from John