3 Mental Models Every PM Needs to Make Decisions

This post is part of our Product Innovator Series. We’re exploring what it takes for businesses to survive and thrive in the product-led era.

Having a set of reliable mental models to call upon to make decisions is perhaps the most powerful thing product managers can do to improve their skills.

The PM’s day-to-day job involves balancing the needs of all different groups, from marketing to engineering, and carving out a clear path for the product. They have to be able to ruthlessly prioritize and make tough decisions with incomplete information. They have to understand human psychology, too. People, though they’re unpredictable and prone to bias, are central to the work of PMs.

The playing field is complex, and relying on arbitrary whims or isolated facts to make it through just won’t work. The fact that Facebook did X & Y to increase their retention rate doesn’t mean the same will work for your company. The latest tactic you read about in a flavor-of-the-week blog post may have worked for someone—but it isn’t necessarily going to work for you.

Mental models help you cut through this noise and complexity to make smarter decisions. They give you an objective heuristic to throw decisions against and analyze. And, best of all, they compound in usefulness—the more you use your mental models, the more effective they (and you) become.

What is a Mental Model

At its core, a mental model is nothing more than a concept or framework that can be used to explain events and phenomena and make decisions. All cognition is based on primitive mental models. What sets the kind of mental models we’re talking about apart is that they’re deployed_ strategically_ in order to solve problems.

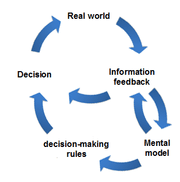

Rather than allow our brains to go on autopilot and treat each new occurrence as a novel event, we apply the mental models in our brain in a reflexive, analytical way:

Events occur in the real world—you get a particular piece of user feedback, or another company launches a feature to compete with your product. Next, your mental models process those events and inform the rules you’re going to use to make decisions—maybe you decide to build a new feature, modify an existing one, or change your positioning in the market. Finally, you act. The cycle continues, with your models and decision-making rules changing as you learn.

Mental models are not static images of the world that you simply apply to make decisions in a rote, formulaic way. Over time, they will evolve as you gain experience in applying them and see the situations in which they’re most useful.

3 Mental Models Every PM Needs

There’s a litany of mental models out there. Berkshire Hathaway’s Charlie Munger claims about 80-90 will carry you through your adult life. Here are three of the most powerful mental models for PMs specifically.

#1. The Problem Hypothesis

The problem hypothesis is a way to think about the viability of your product in a concrete, testable way.

It works by reframing your idea for a product as a very specific problem. Say you’ve built a website that lets people order groceries and get them faster. That’s an idea that sounds like it could be good. It could also be bad. It’s hard to tell. When you reframe it as a problem, however, you see it differently:

People like to buy groceries, but it takes them too long to get to the store and actually buy them.

This is no longer a situation where you can say, “Hmm, could be good—could be bad.”

Instead, you have a clearly verifiable statement. People like to buy groceries, but it takes too long— this is something that you can easily prove to be true or false in a few steps:

- Go out and talk to the people waiting outside of Whole Foods for their Lyft to arrive.

- Ask them how much time they spend grocery shopping every week.

- Look everywhere for data to either prove that your hypothesis is correct or incorrect.

- Use what you learn to either keep building, ditch the project, or pivot to build something more aligned with what people really need.

The simplicity of this technique is deceptive. Used correctly, the problem hypothesis can turn seemingly arbitrary decisions into ones you can validate quite easily.

Related Reading: 9 Mental Models to Build Better Products

#2. Inversion

Many problems resist being solved “from the front.” They demand that you solve them backwards or from an unintuitive angle. This is the art of inversion.

Sometimes the question should not be: “What features do we build?” Rather, it should be: “What features would destroy this product?”

Once you know which features are going to run your product into the ground, you can achieve a simple win just by not doing those.

For PMs, the label of “CEO of the product” can sometimes tempt them into over-relying on their instincts when it comes to building product. However, it is much easier to avoid making mistakes than it is to be perfect all the time.

Inversion is also a powerful way to break out of the repetitive thought-loops that can hurt your team’s ability to learn. We can easily fall into “retro-fatigue” asking questions like, “How can we innovate more?” or “Why did that project not go well?” over and over again. Our brains go on autopilot and start giving similar-sounding answers.

That is why asking questions like “What can we do to innovate less?” can be such a powerful rhetorical technique. It provides you with a slightly different point of view—but one that is usually much more insightful.

#3. The 5 Whys

When you’re faced with a problem, a good product manager will always ask “Why?” five times.

Going through the “5 Whys” helps you understand the core symptom behind a problem, not just its surface consequences. Let’s say you get an angry email from a customer who is annoyed because they didn’t get a delivery until two hours after the close of their delivery window. You file the problem away in your brain:

Problem: A customer is upset because their delivery was late.

A busy PM who is not following the “5 Whys” mental model would probably make a quick decision to do whatever it took to make the situation resolve itself quickly—give a refund, offer a future discount, etc. That would get the problem solved, but only until the same problem arises with another customer.

A PM who is thinking about the future and knows the “5 Whys” model would go through a process of questioning to help identify the root problem:

Problem: A customer is upset because their delivery was late.

- Why? Because they didn’t know it was going to be late, so they wasted their hour-long break from work waiting for us.

- Why? Because no email notification was ever triggered even when we recognized that their delivery was going to be late.

- Why? Because our email notification system pulls transaction data to confirm orders. But it doesn’t pull information from our logistics stack to tell us if an order is going to be delayed.

- Why? Because we’ve relied on drivers to tell customers when they believe they’re going to be late to a delivery.

- Why? Because when we were smaller, this kind of compromise made sense. Building out this notification system was generally less expensive than dealing with manual notifications.

This kind of questioning is powerful. It takes us from a surface problem that we can make go away quickly (with no learnings) to one that reveals a deeper, systematic, scaling issue—one that will recur unless changes are made.

Related Reading: 8 Data Science Skills that Every Employee Needs

No Shortcuts

Our brains love shortcuts. While some call mental models “shortcuts for the brain,” the truth is that mental models more often _slow us down. _They help counteract the kind of short-term, inefficient thinking we run into when we let our brains run on autopilot.

By running all of your decisions and problems through various mental models, you can learn more from your mistakes. You can shore up your worst blindspots, make decisions you are confident with and ultimately, become a better product manager.

This post is part of our Product Innovator Series. We’re exploring what it takes for businesses to survive and thrive in the product-led era. If you’d like us to take on a particular topic under this theme, we’d love to hear from you. Please leave a comment below.

Featured photo by Denys Nevozhai on Unsplash

Hiten Shah

Co-founder of Crazy Egg

Hiten Shah is co-founder of several SaaS businesses including, Quick Sprout, Crazy Egg & Draftsend.

More from Hiten