How Product Managers Can Build Uncommonly Good Judgment

Learn how to avoid bias, become comfortable with ambiguity, and redefine failure within the product management field.

In my book, I discuss how “uncommonly good judgment” is one of the five immutable truths of great product managers. According to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, judgment is “the process of forming an opinion or evaluation by discerning and comparing.” In the context of product management, judgment typically comes down to using our market, business, and customer knowledge to make decisions for the product… which features to prioritize, customer segment to target, idea to research first, and so on.

Let me be clear about one thing: “uncommonly good judgment” does not mean always making the right decision. In product management there is rarely a clear right or wrong answer. We are often investigating several potentially good options, and we prioritize the one we believe is best according to the information we have at the time. But even the very best product manager gets it wrong sometimes. That’s just part of the job. Product managers who have good judgment do a few things really well that give them a better chance at making good decisions.

Here’s what you can do to build uncommonly good judgment in product management:

Avoid cognitive biases as much as possible

Decisions and judgment rely on an evaluation of information. Cognitive biases are prevalent in product management and can impact the quality of the information we use in these evaluations. Some common biases in product management include:

Solution Bias

Solution bias is when we jump straight into solution mode before fully exploring and understanding a problem. It is virtually impossible to make good judgments on something you don’t fully understand. This is why people with good judgment tend to ask a lot of questions. They are never entirely comfortable that they have all of the context they need. They will make decisions when the time is right but rarely before they have a certain confidence level in the problem space.

Confirmation Bias

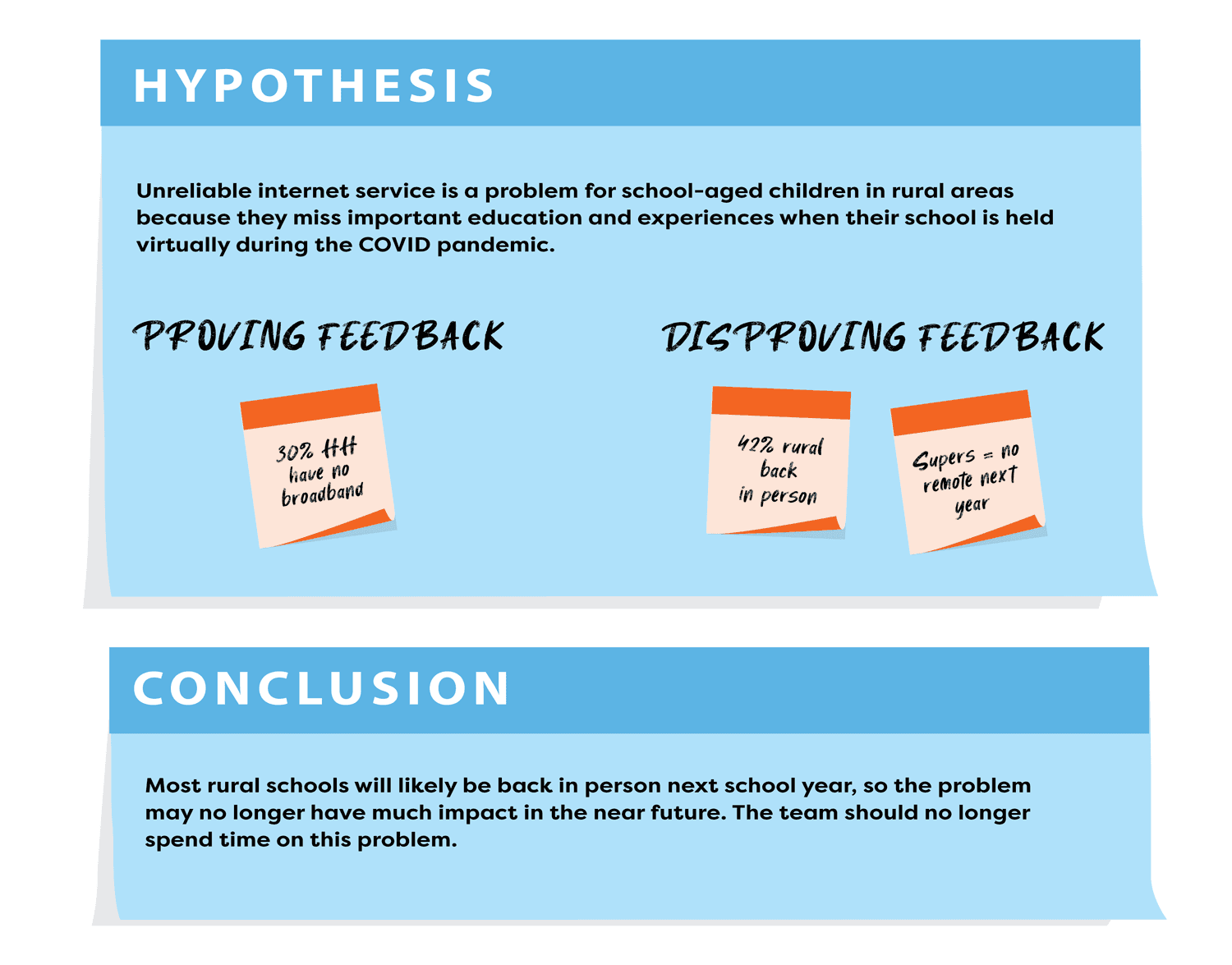

Confirmation bias is the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of one’s existing beliefs or theories. This is one of the most common biases, and we are all guilty of it. In product management, we work off hypotheses. We hypothesize what problems are most important to solve. We imagine what creative solution will make customers flock to us. We theorize on how our organization’s resources and competencies position us for success. The problem is that we often tailor our actions to prove our hypotheses. One of the most effective ways to avoid such bias—and maintain better judgment—is to not only search for data to justify and prove your hypothesis but also actively look for and document information that may disprove it. Using this exercise, you can often “talk yourself out” of something you once fiercely believed.

Framing

Framing refers to the fact that a person reacts differently to information based on how that information is presented. This, in conjunction with confirmation bias, sometimes leads us to tailor the way we share information with customers in order to steer their responses. Often we do this subconsciously through the way we ask questions.

For example, a product manager who asks a customer, “our new feature is like the competitor’s but 30% faster. How does that sound to you?” will likely get an answer of something like, “that sounds really good. A nice improvement.”

Whereas a product manager who asks, “you know that feature we talked about? How would it being 30% faster help your team? Can you identify any tangible benefits with doing that task more quickly?” may give some less biased feedback.

Better yet, “what are some ways that you would like to see that product feature improved to help your team?” may highlight that slowness isn’t even on their list of complaints.

It’s not our job in product management to lead the customer into a particular response. In fact, quite the opposite. We want the most unbiased feedback possible to use as we are making decisions.

Rely on data but become comfortable with ambiguity

Data is a critical part of product management. There really shouldn’t be a product manager out there today who is still making decisions purely on gut. Successful product managers use data to find patterns, prioritize features, illuminate customer pain points, and proactively identify potential issues and opportunities.

We are often inundated with all sorts of information and data, but not all of it is material to the problem at hand. Every piece of information is not equal in value. Some information is incredibly pertinent; some is superfluous. Using the right data at the right time is a key skill in good judgment.

For example, a worldwide microchip shortage has impacted products from automobiles to pacemakers to washing machines. Product managers of these products are now prioritizing supply chain data over anything else. Even if data shows high demand, if the supply side cannot keep up, for now there may be other priorities to explore.

However, even with all of the data at our fingertips today, we still work in a state of ambiguity. There are no sure bets in product management. Virtually everything we do is a prediction about some future outcome. We predict which problem to solve for the customer. We predict which solution will best solve that problem. We predict what the market will look like in three years and what revenue our predicted solution to our predicted problem will reap in that market.

This reality paralyzes many product managers. Fearful of making the wrong decision, they avoid acting, looking for the perfect data to confirm a direction. Great product managers realize there is no perfect data and act anyway.

Redefine failure

One thing people with good judgment do to become comfortable in an ambiguous environment is to redefine what failure means. A main reason people are uncomfortable making decisions clouded in uncertainty is because of the potential impact on their reputation if the decision goes awry. Great product managers know that even if something does not work out the way it was planned, there are still lessons to be learned. They embrace those lessons, share them transparently with the team, and are clear on what they will do differently next time.

Product management is far from a game of perfection. We will always get something wrong, and the way we deal with those “failures” and learn from them is what can set us apart.

Work on these three things—avoiding biases, embracing data yet become comfortable with some ambiguity, and redefine what failure means to you—and you will be well on your way to good judgment. To continue your learning on becoming a great PM, check out IMMUTABLE: 5 Truths of Great Product Managers today.

JJ Rorie

CEO, Great Product Management

JJ Rorie is faculty at Johns Hopkins University, teaching undergraduate and graduate-level product management courses. She is the author of "IMMUTABLE: 5 Truths of Great Product Managers," and is Chief Executive Officer of Great Product Management. JJ is a speaker, advisor, trainer, and coach, having worked with some of the world's largest companies, and also hosts the popular podcast Product Voices.

More from JJ