The Certainty Trap

Let's talk about communicating uncertainty in product development.

How do you foster productive discussions about uncertainty that 1) don’t end up in analysis paralysis, and 2) don’t end up making you appear “weak” or “unprepared”?

We often reward what I call, “Certainty Theater,” the phenomenon of consciously or unconsciously inflating the certainty we have about decisions. Product teams are particularly prone to it. Let me explain what I mean with an example.

Leaders/managers frequently make the mistake of glossing over uncertainty because they are concerned that people will be demotivated.

I remember when a CTO asked me for a more detailed, solution-oriented roadmap. I resisted. He asked repeatedly.

I finally caved and spent twenty minutes sketching out a dozen ideas based mostly on gut feel. “John really nailed this! He has a super clear vision. We need to start on this in Q2!” Ooof…not my best work.

I was participating in Certainty Theater (a not-so-distant relative to Success Theater).

Why did I resist this ask from the CTO? Because I knew that the company would deliver better outcomes if a cross-functional team of designers, developers, and customers started together instead of me taking a stab at it alone. If I committed to that big batch of prescriptive work before we started together, we’d miss out on all sorts of opportunities to make better decisions.

Why did he insist? He saw the advantages of converging quickly on a plan (staffing and setting expectations), and not the disadvantages (a less than optimal solution, not engaging the team, etc.).

You notice this pattern of rewarding certainty all over organizations.

- “Bring me solutions, not problems!”

- Annual budgeting and inflated plans to “get the headcount”.

- The “solid roadmap”.

- The persuasive pitch.

- The startup that’s “killing it” (but not).

- Delivering “predictably”.

- New executives are asked to dream up a plan in 60 days and “execute”.

- “Getting ahead” of the work.

- 4 business days to plan the whole next quarter.

- Pitching a new product vision to aid in fundraising.

- The “crystal clear mission”.

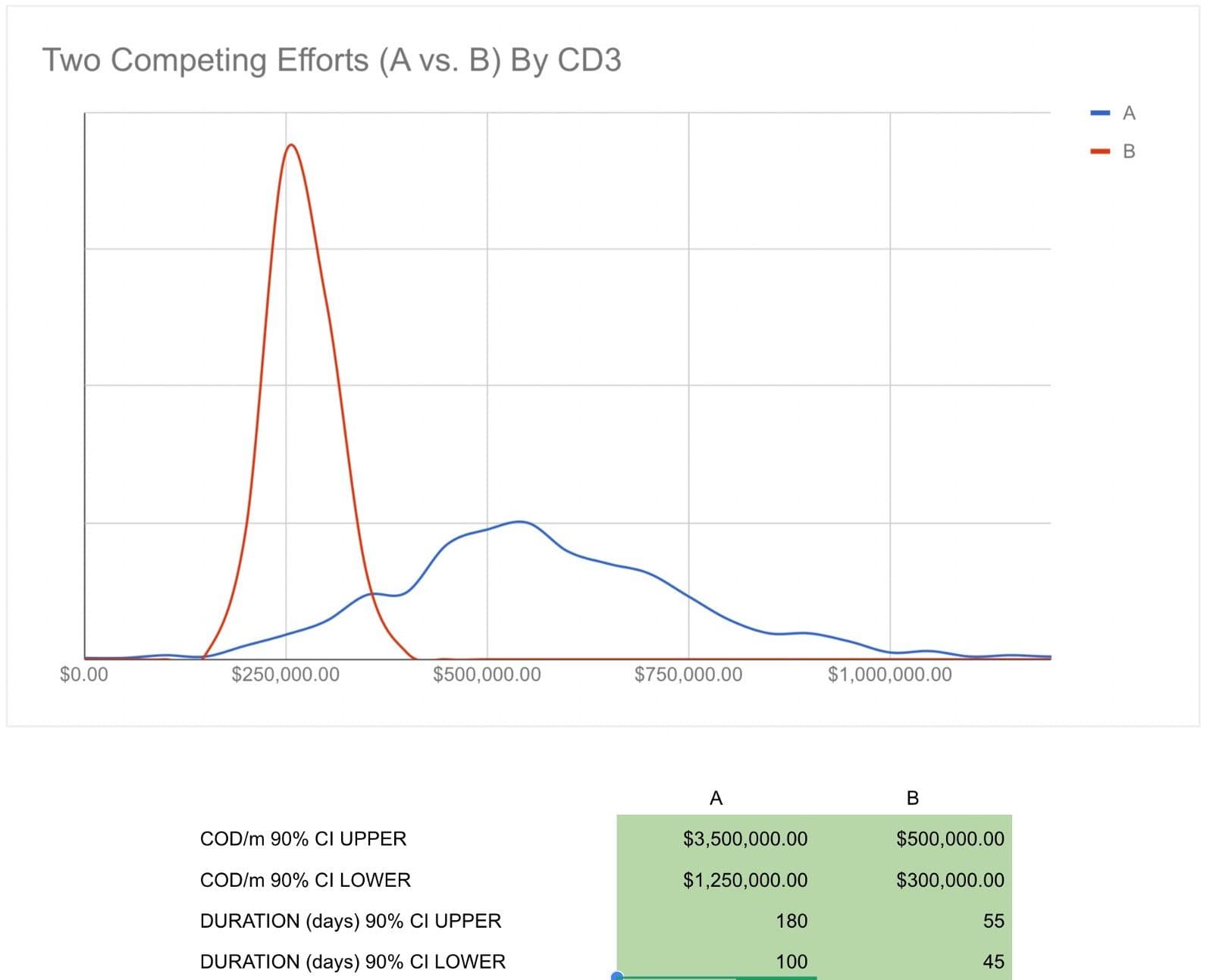

Take this example of two competing efforts:

- The blue line, ”A” represents a big opportunity (with 1–3x range in value , and could take 100–180 days.

- The red line, “B” is a “certain” 45–55d, and a more certain (but lower) opportunity size.

We’ll often pick the red line B because we’re lured in by that certainty. We’re not rational actors, and our organizations are not necessarily optimized for global outcomes/benefits. But blue line A is the better choice–there’s simply more upside potential despite the uncertainty.

Leaders/managers frequently make the mistake of glossing over uncertainty because they are concerned that people will be demotivated. What they miss is that people DO crave certainty in some things (like keeping their job, that their work is making a difference, that they’ll get opportunities to learn/advance, and that they’ll get access to the right tools-of-the-trade), but that doesn’t mean they crave certainty in all things. Take my example. The opportunity was, with a high degree of certainty, the right thing to focus on (inspiring and purpose-driven), but the precise interventions were unknown.

Communicating about uncertainty with certainty is an acquired skill.

I’ve found that people respond to a crystal clear delineation between the known and unknown. They appreciate data when it is available but not “made up stuff”. They want to see that you tried and that there’s some coherent rationale to the risk/bet you’re proposing. Perhaps above all, they want to know that you’re taking some of the burden for the uncertainty, and not just foisting it on them. It’s about a coherent explanation. For product development teams that can be about crafting a bounded “game” / experiment that holds water, instead of just leaving things “open ended”. They want structure and rigor, not certainty (if that makes any sense).

People respond to a crystal clear delineation between the known and unknown. They appreciate data when it is available but not “made up stuff”.

So how do you foster productive discussions about uncertainty? Pitch your excitement for solving a compelling problem while conveying that it will likely take a couple tries to get to make progress.

John Cutler

Former Product Evangelist, Amplitude

John Cutler is a former product evangelist and coach at Amplitude.

More from John